Happiness

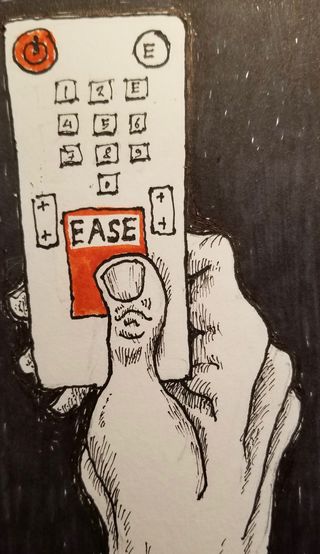

Is America's Obsession With Ease Bringing Us Down?

The culture of meds, fast food, and sedentary life may leave us unhappy.

Posted March 15, 2019

Last autumn I was asked to speak at the Con Edison safety conference held in Flushing Meadows, Queens; and it was the proverbial "tough act to follow" that preceded me, for the first speaker was Austin Eubanks, a survivor of the Columbine massacre, who on top of his formidable skills as a lecturer, had a riveting tale to tell.

As a gifted high school student, he and his best friend were in the Colorado school's library on the afternoon of April 20th, 1999, when two teens, Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris, burst in with handgun, carbine, and shotgun and walked through the school, systematically shooting everyone they saw. Eubanks was hit twice, but survived by playing dead. His best friend, Corey, 11 other classmates, and one teacher were killed outright. The shooters also killed themselves.

In the months and years that followed, Eubanks says, he was treated, and over-treated, by medical and psychiatric professionals who massively subscribed painkillers for both physical and mental trauma. When the Prozac, Oxycodone, and Oxycontin didn't work to palliate his profound grief, survivor's guilt, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, he resorted to illegal drugs, from cocaine to speed to heroin. He took on a wife and a high-profile professional job and lost them both.

Finally, he came to realize that he had become a victim, not just of a national epidemic of gun violence, but of a national culture that focuses solely on eliminating pain without examining the root causes thereof. If it hurts, anesthetize it, seemed to be the watchword of everyone who, even with the best of intentions, sought to help a man who was clearly suffering intensely.

No one ever allowed him to suffer it out, to feel his pain, and try to work through it and by understanding and absorbing it, to let him live fully again. It was only when he figured this out that he was able to heal.

“You want to feel better immediately,” Eubanks told The Guardian newspaper shortly after another mass school shooting in Parkland, Florida, “[but] you have to have the courage to sit in and feel it, and if you can do that long enough, you will come out on the other side.”

Anesthetizing pain was certainly the watchword of the Big Pharma companies, such as Purdue, who aggressively marketed Oxycontin, one of the opioids Eubanks was treated with, even when they had data showing oversubscription of such meds was causing an epidemic of opioid addiction. Between 1999 and 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control, opioid addiction killed 400,000 people in the US alone.

(In fact, the Sackler family, who own Purdue, actively took advantage of the addiction epidemic to market meds that Purdue said would counter addiction to the drugs they themselves were selling.)

This "anesthetize the pain" mindset is not confined to therapy or medicine. It pervades American life, where the sole goal seems to be to reduce the percentage of effort or discomfort and by the same token increase the share of ease and comfort, in every aspect of our daily existence.

We are taught, as consumers, that we have a right to avoid discomfort and pain. We are conditioned to avoid complex tastes and instead buy foods rich with the easiest palate satisfaction, ie., salt, fat, and sugar. We are brainwashed to avoid regular beds and insist on the biggest, most comfortable mattresses; we reject worried nights and demand hours of untroubled sleep, using sleep meds if necessary; we refuse boredom and equip our cars with entertainment centers; fleeing the heat of summer or the chill of winter, we demand air-conditioned rooms in August and living quarters warm enough to walk around, clad only in underwear, all February. If our kids are bored in school or hyperactive at home we immediately assume ADHD and prescribe Ritalin. We are told to subscribe (if we can afford it) to health plans, medications and therapies that imply illness, aging and death are all problems that can be cured or at least put off indefinitely with the right pills. When our ease lifestyle still doesn't satisfy we are near-automatically prescribed anti-depressants by well-meaning therapists. We are offered vast ranges of liquor and sea-cruises for the times when, despite all our material riches, we find that we're still not happy.

The problem is this: Too much ease in how we live is actually bad for us. Take our bodies. Our bodies, in a sense, are relics of the past; during the times, long gone, when fat, sugar and salt were in short supply, they were conditioned to associate those ingredients with pleasure-inducing hormones such as serotonin. Those were the epochs—over 90 percent of human history—when our hunter-gatherer ancestors roamed the Earth, eating mostly plants, fish, and lean game; imagine how they would have salivated when confronted with a TV ad for Big Macs! Now that we can eat as much as we want of these ingredients by driving to the nearest MacDonald's or Burger King, we are plagued by epidemics of obesity, high blood pressure, and diabetes. These ills are directly associated with salt, fat, and sugar—not to mention with driving everywhere, as opposed to walking.

By the same token, we default to the ease position in much of the rest of our lives. Instead of taking the time to sit down and talk with a friend, how much easier to exchange a text message. Instead of curling up somewhere quiet and taking a few hours to read a book, with all the subtle involvements of our memory and imagination that implies, how much easier to click on the latest Youtube video, or stream an action movie that requires zero involvement of imagination on our part. (Full disclosure: as a writer of books I am prejudiced in favor of reading.) The advent of increasingly immersive virtual reality serials, in which we will be comprehensively soaked in the exciting and adventurous lives of action heroes and romantic leads, implies a future where getting off the Barcalounger to chase down our own, real-life adventures, of whatever nature, becomes increasingly tiresome.

But, apart from the physical downside, does any of this really sadden us? No science exists to prove that the rise of the ease culture, and the couch potato, has led to a corresponding decrease in personal happiness or fulfillment. However, the circumstantial evidence to that effect is strong. The opioid epidemic Austin Eubanks is fighting is certainly one symptom of societal unhappiness.

The World Happiness Report, generated by a United Nations body, ranks the US as 18th in the general happiness stakes; not a bad showing, perhaps, except that much of survey is weighted toward material factors such as GDP and life expectancy, areas where the US is strong, but which are only indirectly linked to happiness.

The satisfaction that artists (of whatever stripe) experience by working exacting hours, often in rough conditions, while making something beautiful is part of our cultural lore; but anyone who has busted his/her/z's butt at a worthwhile task intuitively understands the connection between the rigors of hard work at a meaningful job and the pleasure to be found in surmounting those rigors. Is it possible that the increasingly insecure, hyper-specialized, often temporary jobs available in the modern "gig economy" simply don't offer the opportunity of finding pleasure in hard work that is complete and fully owned?

A possible indication of what is lacking in our lives is that the top three spots in the world happiness survey are taken by small Scandinavian countries where, according to Time magazine, people are used to a high degree of personal social involvement--in other words, making an effort to interact directly with other humans, as opposed to sitting on the couch exchanging texts and watching "Game of Thrones."

Finally, one thing is certain: to tackle over-population, climate change, and attendant disruption is going to require very hard work and a downturn in living standards, and a reduction in the overall ease-lifestyle of affluent Westerners. The good news, therefore, is this; if and when we really roll up our sleeves and get down to saving the planet, we may well find ourselves the happier for it.