Neuroscience

The Breath in Your Body

The literature and science of shared experience.

Posted June 18, 2020

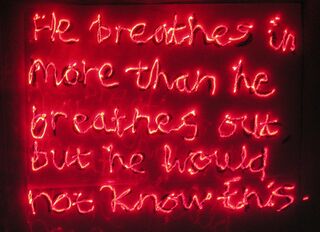

George Floyd’s murder has awakened the world to the injustice of systemic racism. A virus that can destroy human lungs is making this systemic unfairness apparent by disproportionately affecting people of color. Racial injustice has shaped U.S. society from its inception, and those who have suffered from it have fought it all their lives. It is those who have benefited from it, however good their intentions, who are talking about waking up. Why now, considering the number of Black men and women who have been murdered in the past decade? One reason may be that having the breath crushed from your body is a horror to which everyone can relate.

In my field—literary studies—most scholars think that human experiences are shaped by languages and cultures. They resist the notion of universal human experiences because it lets powerful people promote their experiences as universal and invalidate less powerful people’s inner lives. These scholars have a good point, but when it comes to human life functions, I have never been so sure. Western linguistic and cultural roots show a long association of breath with life. “Psyche,” meaning “mind, soul, or spirit,” derives from the ancient Greek word “psukhe,” meaning “breath of life.” “Animate” comes from the classical Latin word “anima,” meaning “air, breath, life, soul, or spirit” (Oxford English Dictionary online). People may have associated life with breath for millennia because of the languages they’ve learned, but it could be the other way around: People refer to life in terms of breath because breathing is a visceral, animal process that all human beings share. To watch a fellow human being asphyxiated, gasping for help, can fill anyone with horror and motivate him or her to act.

In my research, I study the techniques that fiction writers use to help readers imagine characters’ sensations. Gifted writers help readers feel as if they were in characters’ bodies, right there in a story’s scenes. Like neuroscientists, writers know that sensations never happen alone. A person stroking a cat may also admire its black fur and smell chocolate chip cookies baking, but she will be more aware of some of these sensations than others. In When Fiction Feels Real, literary scholar Elaine Auyoung notes that Leo Tolstoy pulls readers into Anna Karenina by describing “small, round objects” such as buttons, which readers can imagine grasping (Auyoung 24). Interdisciplinary scholar G. Gabrielle Starr has shown how imagined movements, sometimes suggested by the rhythm of language, can cue readers to blend multiple sensations (Starr 80-82). Guiding readers into a story often means drawing them into a character’s mind. That is best accomplished by evoking combined sensations in a reader, with some that suggest what’s happening in the background (vision, hearing, smell), and some that show what’s happening in a character’s body (taste and touch).

Recent cultural studies of touch have revealed that this under-respected sense has long been appreciated by scientists (Gilbert 4). The term “touch” in English lumps together several different systems that human bodies use to assess their environments: 1) discriminative touch, such as that used to read Braille; 2) proprioception, which tracks a body’s positions and movements; 3) temperature assessment; 4) pain or irritation detection; and 5) interoception, which reveals the state of the inner organs (Kandel et al. 430).

These different kinds of bodily feedback are detected by different classes of receptors and transmitted along different neural pathways, which merge and share information with other sensory modalities as they move through the nervous system (Purves et al. 114). At any given moment, a person may be aware of some or none of these five “touch” sub-modalities. Breathing often occurs without conscious awareness—until someone tries to stop it.

Interoception, the least studied system of “touch,” has proved to be a vital resource for writers trying to help readers experience the world as a character does. Human languages tend to favor sensory systems with efficient transmission and ample processing space. Because vision, hearing, and fine touch discrimination receive so much attention in so many people, languages often have richer vocabularies to describe sights, sounds, and feelings against the fingertips than they do to convey smells, tastes, or gastrointestinal misery.

For this reason, a creative description of bodily unease can help a reader identify with a character. In The God of Small Things, when 7-year-old Estha is sexually abused by a middle-aged man, Arundhati Roy’s narrator tells readers that the boy has “a greenwavy, thick-watery, lumpy, seaweedy, floaty, bottomless-bottomful feeling” (Roy 107). This description that combines sight, movement, and texture helps convey the inner world of a boy sick in every sense. Estha’s feeling emerges as it might in a reader: through improvised approximations.

Like nausea, breathing defies description because it so often escapes awareness. Meditation programs train students to focus on breathing because gaining awareness of it opens consciousness to all of interoception. Heightened awareness of what your body is doing can break the hold of obsessions and open your mind to the surrounding world. Communication and media scholar Ellen Esrock has proposed that readers may respond to stories interoceptively, for instance, by unconsciously adjusting the rhythm of their breathing (Esrock 79).

A reader who can feel a character breathe can share the rhythm of that person’s life. In Edwidge Danticat’s Breath, Eyes, Memory, the protagonist Sophie’s mother, who had Sophie after being raped, feels tormented when she becomes pregnant with a new child. She tells Sophie: “It bites at the inside of my stomach like a leech. Last night after I talked to Marc [the child’s father] about letting it go, I felt the skin getting tight on my belly and for a whole minute I couldn’t breathe. I had to lie down and say I had changed my mind before I could breathe normally” (Danticat 194).

Letting Sophie’s mother say what her body is doing accomplishes more than offering emotion-words for what she feels. The sense of being bitten from within, the tightness, and the inability to draw breath show that even decades after her rape, Sophie’s mother still feels trapped by her rapist, whom she senses in her unborn child. Breath, Eyes, Memory depicts a world in which awareness of your momentary sensations helps you appreciate the lives that have enabled your own and the lives that you will nourish in turn.

Like no other internal sensation, breathing helps people appreciate their bonds with others by reminding them of the fragility of their own lives. Thinking about your breathing can be humbling, and in the era of the coronavirus, a careless breath can kill. It has taken too long, but the sight of a man denied the right to breathe may finally have inspired millions of people to imagine what he felt—not to “see” the world from his perspective, but to feel it viscerally, which means more. After seeing the video of George Floyd’s murder, I dreamed that someone was crushing my neck, and I woke up with a migraine that lasted three days. When it cleared, I went out to march for justice.

References

Auyoung, E. (2018). When Fiction Feels Real: Representation and the Reading Mind. New York: Oxford University Press.

Danticat, E. (2015). Breath, Eyes, Memory. New York: Soho Press.

Gilbert, P. K. (2014). “The Will to Touch: David Copperfield’s Hand.” Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, 19: 1-15.

Kandel, E. R., et al. (2013). Principles of Neural Science. 5th ed., New York: McGraw Hill.

Oxford English Dictionary Online.

Roy, A. (1997). The God of Small Things. London: Harper Collins.

Starr, G. G. (2013). Feeling Beauty: The Neuroscience of Aesthetic Experience. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Esrock, E. (2004). "Embodying Literature." Journal of Consciousness Studies, 11: 79-89.