Aging

Retirement Isn't Always a Walk in the Park

How do you think ahead to retirement?

Posted February 21, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

About 10 years ago, my patient Gene retired as a professor of Dramaturgy and Dramatic Criticism at a local university. Most people don’t know what dramaturgy is, or what the dramaturge (its practitioner) actually does, this was partly why he left. “I was the intellectual in the Theater Department,” he told me, “but that made me obsolete.”

Gene was definitely old-school: bow-tied, tweedy, always clutching a script whose author dreamed of summer stock at Williamstown, the Guthrie, or the Hartford Stage.

The dramaturge provides these places—and many others—with learned critiques of dramatic literature. What are the play’s themes, its context, its characters’ psychological dilemmas? Is it well-structured? How is the play situated historically? Is it important? He also has to understand the business of theater. Could a play be produced within budget? Would it appeal to a likely audience? Who’d be good in the leading role?

In their quiet way, dramaturges have immense power over what gets produced; when they draft a play’s liner-notes, they can determine how it’s received. The only problem was that nobody studied theater anymore to become a dramaturge. Gene's cadre of students was dwindling.

“You know,” he told me, “everyone wants to study acting, or sound design, lighting, directing, playwriting—the stuff that’s heavy on technique. The Technical Design and Production students are all engineers.”

This lament (which he’d expounded on at length in the few professional journals still run by his pals) echoed the old-school psychoanalysts’ objection to psychopharmacology. Where was the theoretical grounding, the centuries of brilliant learning, the human factor?

He conveyed a sense of tremendous loss as if the soul of what it meant to be in The Theater had fled forever, leaving behind a semi-mechanized simulacrum (that students seemed to adore). “The study of drama has become deracinated,” he said. “Now it’s all flashing lights.”

Gene left.

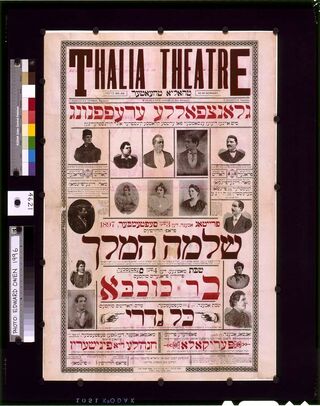

He intended to finish his book on the revival of Yiddish theater and to write long-form theater critiques for alternative newspapers in alternative cities with start-up theater companies. He expected he’d still be judging playwriting competitions, and that he’d be asked to write liner-notes for revivals of classic plays. Of course, he hoped to catch up on his reading. He hoped to catch up on his sleep. At 65, it seemed like he’d have plenty to do.

The problems started when he turned 70. “My wife threw a party for me,” he said, “and when I blew out the candles, it was like all the lights went out.” What Gene meant, was that he had no idea how he was going to fill up his days. The people at the party—some playwrights, a few theater critics, a producer—were still in the game, and just their presence made him feel like a has-been, an outsider longing to get back in.

“I finished the book, and all the other stuff was small potatoes,” he said. “Everyone else talked about their latest projects, and what I had to say sounded trivial.”

By the time he came to see me, which was a couple of years later, Gene had tried various ways to keep his hand in, but they didn’t amount to much. He gave some lectures at synagogues through a program run by the state. He volunteered at a bookstore. He helped a private collector decide whether to auction off his 19th-century theatrical artifacts (the collector ignored his advice). But the people with whom he engaged didn’t seem serious enough. They felt like his students—admiring, but sort of in the way that you’d admire an antique.

What Gene lacked at this point was a sense of purpose. When he was at the university, he was busy putting on plays, even though the ranks of his students were thinning. He got involved in rehearsals and helped directors understand the messy undercurrents of Continental plays in translation. He helped condense three-hour plays into manageable productions (what’s OK to leave out?), and he explained Tom Stoppard to everybody. There was enough going on that he never lacked for projects. Plus, the theater reporters on the student newspaper always wanted his take, and they frequently gave him a platform to sound off. At the opening of the season, the campus radio station would interview him. The Department Chair encouraged his research, and financed summer trips to archives all over the world (Gene read German and French, which meant he could always think up something exciting). His wife came along, and they’d have a great time.

But then all that stopped. “What was I thinking?” he mused during one of our sessions. “OK, so I didn’t have my pick of students anymore, but I had a life there—I was somebody.”

The idea of not being “somebody” anymore had significant consequences for Gene. First of all, he was lonely. When the thrill of having free time gradually wore off, he realized that he had only make-work that he made himself do. He couldn’t call most of his buddies during the week because they were working. He couldn’t offer his services to major theatrical institutions since he no longer had the stature of a working theatrical professional. He was scared to death of getting on his wife’s nerves.

Gene’s wife, Jessica, was an assistant vice president at a bank in the city. “Everybody’s an Assistant Vice President,” she’d say, laughing off her title. But Jessica was smart and hardworking. She knew her way around 401(k)s. She was 10 years younger than Gene and had every intention of remaining at her job.

When she came home at night, and Gene complained that he’d had nothing to do but the laundry, she was sympathetic but at a loss with regard to how she could help. “Why don’t you start another book,” she’d say, “or maybe see if you could get a column in Rolling Stone?”

Her ideas struck him as somewhere between impossible and preposterous. He knew that she meant well and that she loved him deeply, but she simply had no idea how corrosive his isolation had become. He couldn’t imagine undertaking a brand new, large-scale initiative anymore. He didn’t think he was capable of sustaining it.

Gene was obviously depressed. The less he did, the less he thought he could do. When he did stuff that felt trivial and unsatisfying, he felt that such stuff was all he could do. He wanted real work ... and he didn’t. He missed what he had done, and thought that he’d kissed his life away forever.

He confided in me that, for a while, he wondered about asking Jessica to retire. But he knew that she wouldn’t, not least because she liked going to work every day—just like he had. Besides, he liked the money that Jessica brought in. They didn’t really need her salary, but it paid for the new 52-inch TV they’d just bought and the apartment in London that they’d rented for the past three years. It made possible as many theater tickets as they could use, with dinner afterward. So, Gene said nothing. He spent hours on the websites of cruise lines comparing their latest packages.

What is the lesson that I draw from Gene’s journey through retirement? In leaving his position, he thought he was pursuing happiness. But he didn’t look around. He failed to understand what life would be like outside his cosseted little enclave in the Theater Department. He didn’t take into account how much his work, however diminished, still meant to his sense of himself and his well-being. He thought he’d always have a purpose, and discovered that he wouldn’t. He knew he’d notice the transition, but thought he’d just trade the bad parts of his professional life for some new incarnation that he’d like better. It was like people who switch careers without fully investigating what they’re getting into. It was, in fact, pollyannaish.

Gene certainly didn’t contemplate how his wife would react. Jessica encouraged him to get involved with new, interesting projects. But what she didn’t and couldn’t know was that once you leave a well-respected position in the theater, you don’t just become a Grand Old Man. You’re more likely to be an old man, period. Jessica tended to romanticize her husband’s previous work, and every time she brought it up to Gene by way of trying to help, she only made him cringe (once he actually yelled at her, and was full of remorse for days).

Gene also hadn’t contemplated how his friends, who were still working, just wouldn’t be available for weekday lunches or a walk in the park. He just hadn’t taken stock of the landscape of intimates whom he’d want to call on, but couldn’t.

Sometimes, of course, we have to retire. We’re too old for the work, or it’s simply started to get to us in ways we cannot abide. But Gene hadn’t been there. He was annoyed at the students’ shifting interests, but he’d dramatized that shift into an ideological crisis—a total disenchantment with the academic theater. He had allowed himself to become a purist in the worst sense; he became self-defeating. He created only a spotty scenario for how his life would proceed post-retirement; he’d never have given it a positive critique had it been the basis of a play he’d been asked to read. He’d let himself be led on, giving up the still-OK for an uncertainty.

I am still trying to help Gene. But significant damage has been done.

The moral of his story, therefore, is that before we voluntarily leave a job that underwrites our identity—which most jobs do, one way or another—we should think about how we can adequately support our identity once we’ve left. We should talk to people who’ve made similar moves. We should investigate opportunities and actually try to line them up. Retirement is, literally, no walk in the park. It’s a serious phase of our life, and we need to prepare for it honestly and competently.