Bias

Are Scientists Biased Against Women Scientists? Part II

Does the relevant evidence show sexism?

Posted June 18, 2019

This is the second in a two-part series on the evidence of gender bias in science. In the first part, I define bias, and describe what I mean by “gender bias in science” – see Part I for the details. In short, I am focusing on gender bias in scientists’ evaluations of men and women in science (e.g., peer review in publications and grants, hiring, etc.). By "science" here, I refer to both natural and social sciences.

Part One identified five broad patterns of findings in the scientific literature on gender bias in science, and provided a concrete example of each:

1. Scientists are biased against women

2. Scientists are unbiased

3. Scientists are biased against men.

4. Ingroup bias: Women are biased in favor of women; men are biased in favor of men. This can get even trickier, though, because one group may show ingroup bias but the other may not. Men may be biased in favor of men, but women may be unbiased; or the reverse may be true: women may be biased in favor or women, and men may be unbiased.

5. Research that reached the conclusion that there is bias against women scientists, but which has been subject to highly plausible doubts, re-analyses concluding otherwise, or outright refutation.

In this post, I provide citation info and a cursory description of the main finding for every study of gender bias in scientists’ evaluations of men and women in science that I could find. If you know of one that is not listed here, please let me know. If it belongs, I will add it.

If you are interested in tracking down these articles, most can be found by using Google Scholar and searching for the citation provided here. Sometimes, the article may be behind a paywall. If you are affiliated with a university, you can usually find the full article via your library. Some authors have their papers on their University websites. However, I would never recommend someone use a piratical site to get around a paywall, and people who use sites such as [sci-hub dot tw] do so at their own risk.

Note: The best studies of bias control for objective quality. Those are starred (*). Studies without a star, are vulnerable to alternative explanations. Studies are categorized by their predominant finding. A paper finding bias on four measures and no bias on two would be categorized as a bias study; a study finding no bias on four measures, bias against women on one, and bias against men on one would be characterized under unbiased.

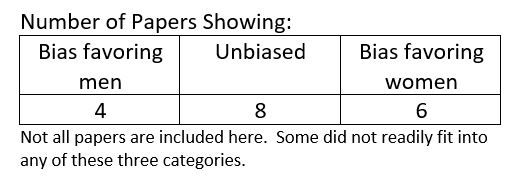

Brown & Samuels (2018, described below) is a gateway to five separate papers showing unbiased responding and is counted as five. What is shown above is the number of papers, not the number of studies; some papers reported several studies; most of those showed either unbiased judgments or biases favoring women. Bias favoring women also includes the two papers showing women scientists favored women but men were unbiased (i.e., overall bias favored women). Studies interpreted by their authors as having shown bias against women, but which have either been debunked or which are open to obvious alternative explanations, are not displayed in this table.

Bias favoring men: The four papers shown under "Scientists are biased against women."

Unbiased: Brown & Samuels (2018) = 5 + 3 other papers listed under "Unbiased."

Bias favoring women: Four papers listed under "Bias favoring women" plus the two papers listed under "Women scientists favor women; men were egalitarian."

"Bias" favoring women may be technically valid, but may not capture the full complexity of what is going on. In some fields, the underrepresentation of women is severe, and many in those fields wish to redress the imbalance so that when two candidates are close on merit, the department will often give the nod to the woman.

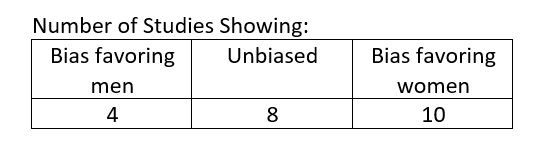

All papers (unless I am mistaken, and, if so, please let me know and I will change it) reported a single study with two exceptions: Ceci et al (2014) was a review and presented lots of other people's data; I only counted it as "one" study because the National Research Council data appears nowhere else.

The other exception is Williams & Ceci (2015) which reported five studies. So if we count studies instead of papers, the empirical literature shows this:

1. Scientists are biased against women

*Eaton et al (2019). How Gender and Race Stereotypes Impact the Advancement of Scholars in STEM: Professors’ Biased Evaluations of Physics and Biology Post-Doctoral Candidates. Sex Roles. Online version here. (Context: Professors evaluations of the vitae of people who recently completed their Ph.D.’s in biology or physics).

*Moss-Racusin et al (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109, 16474–16479. (context: hiring a lab manager in biology, chemistry, and physics).

*Steinpreis, R. E., Anders, K. A., & Ritzke, D. (1999). The Impact of Gender on the Review of the Curricula Vitae of Job Applicants and Tenure Candidates: A National Empirical Study. Sex Roles, 41, 509–528. (context: academic hiring in psychology; note: although they find bias in hiring, they did not find bias in tenure decisions).

Roberts, S. G., & Verhoef, T. (2016). Double-blind reviewing at EvoLang 11 reveals gender bias. Journal of Language Evolution, 1, 163–167. (context: acceptance of papers at a conference). It’s a weird result that begs for replication. Before the double-blind review, papers by men and women were rated similarly. For the one year that double-blind review was used, papers by women were rated higher than those of men.

2. Scientists are Unbiased

Brown, N. E., & Samuels, D. (2018). Gender in the journals, Continued. PS: Political Science and Politics. (Context: Peer review Important Note: This is an introductory article to a special journal issue; in that special issue, five separate papers report five separate investigations, all linked in this overview article and all five found no evidence of gender bias in five separate political science journals)

*Forscher et al (2019). Little race or gender bias in an experiment of initial review of NIH R01 grant proposals. Nature: Human Behavior 3, 257-264. (Context: Grant funding across a wide range of scientific disciplines at The National Institutes of Health).

Pohlhaus, J. R., Jiang, H., Wagner, R. M., Schaffer, W. T. & Pinn, V. W. (2011). Sex Differences in Application, Success, and Funding Rates for NIH Extramural Programs, Acad. Med. 86, 759–767. (Context: grant funding at NIH across many scientific disciplines).

Tomkins et al (2017). Reviewer bias in single- versus double-blind peer review. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114, 12708–12713. (Context: Accepting papers for presentation at a computer science conference).

3. Scientists are biased in favor of women and/or against men

Ceci, S.J., Ginther, D. K., Kahn, S. & Williams, W. M. (2014). Women in academic science: A changing landscape. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 15, 75-141. (Context: academic hiring across a wide range of scientific disciplines).

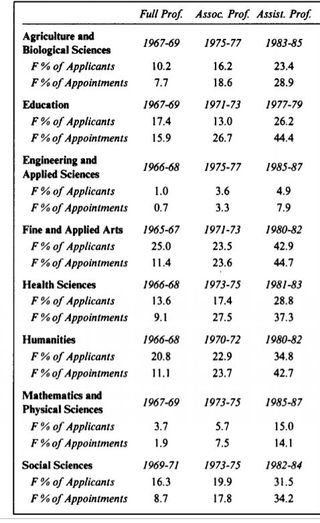

A key table from their paper is shown here. It is something of a "bottom line" table. Across many STEM disciplines, it shows that disproportionately more women were interviewed than applied; and disproportionately more were hired than were interviewed. Although the data are reported in the Ceci et al (2014) article, they were collected by the National Research Council, an arm of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences.

These data might not constitute evidence of bias if women consistently outperformed men on academic criteria. However, Ceci et al (2014) review evidence that this is not the case, and, if anything, the gender gap in measurable achievements (publications, grants, etc.) is that men usually have more. Of course, such gaps themselves may reflect bias, but: 1. That is an issue beyond the scope of this essay. 2. Whereas bias might or might not explain gaps in achievement, as long as achievements favor men it refutes the "women outperformed men" explanation for the results in this table.

Irvine, A. D. (1996). Jack and Jill and employment equity. Dialogue: Canadian Philosophical Review, 35, 255-292. (Context: Hiring). This paper reviewed gender gaps in hiring across academic disciplines in Canada, but is included here because science disciplines were among those included. Here is a key finding:

This table shows that sexist bias was alive and well through the 1960s, began to reverse in the 1970s, and generally reversed by the 1980s. As such, it is consistent with Ceci & Williams' (2014) findings regarding U.S. universities.

Lutter, M. & Schroeder, M. (2016). Who Becomes a Tenured Professor, and Why? Panel Data Evidence from German Sociology, 1980–2013. Research Policy, 45, 999-1013. (Context: Tenure. Women needed 23-44% fewer publications to get tenure in German sociology departments).

*Williams, W. M., & Ceci, S. J. (2015). National hiring experiments reveal 2:1 faculty preference for women on STEM tenure track. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112, 5360-5365. (Context: Five expeirments involved evaluating candidates to hire across a range of scientific disciplines).

4. Scientists show symmetric ingroup biases by sex (men favor men; women favor women).

Moore, M. (1978). Discrimination or favoritism? Sex bias in book review. American Psychologist, 33, 936-938. (Context: Book reviews; men favored books by men; women favored books by women).

5. Women scientists favor women; men were egalitarian

Vedlkamp, C.L.S., et al (2017). Who believes in the storybook image of the scientist? Accountability in Research, 24, 127–151. (Context: Male and female scientists indicated how rational, objective, etc. male and female scientists generally are).

*Lloyd, M. (1990). Gender factors in reviewer recommendations for manuscript publication. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 23, 539-543. (Context: reviewer evaluations for 5 social science journals).

6. Women were egalitarian; men favored men. I found no research in this category.

7. Research that has found bias, or in some cases, a mere gap and interpreted the gap as bias, but has been subject to credible re-analyses or alternative interpretations rendering the meaning of the finding unclear.

Nittrouer, C. et al (2018). Gender disparities in colloquium speakers at top universities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115, 104-108. (Context: Invitation to give talks at top universities). More men than women were speakers. The paper eliminates many alternative explanations (e.g., women turn down more invitations). However, one alternative was that there was a larger pool of highly accomplished men than women (which could lead to more invitations for men without sex bias, if invitations were based on accomplishments).

Van der Lee & Ellemers, N. (2015). Gender contributes to personal research funding success in The Netherlands. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112, 12349–12353. (Context: Grant funding). The main finding of bias was debunked as an instance of Simpson’s Paradox (I explained Simpson's Paradox here) by:

Albers, C. J. (2015). Dutch research funding, gender bias, and Simpson’s paradox. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112, E6828–E6829. In short, fewer women got funded, not because of bias, but because more women applied in fields where funding is more difficult.

Wenneras, C., & Wold, A. (1997). Nepotism and sexism in peer-review. Nature, 387, 341-343. (Context: Grant funding in Sweden). Women received fewer grants, but this research did not even attempt to assess Simpson’s Paradox, e.g., were women more likely to apply in fields where funding is more difficult? This is plausible, because women entered the social sciences in much larger numbers and much earlier than they entered natural sciences (see here or here), and because funding is generally more difficult in the social sciences.

8. Complex results that do not easily fit anywhere above.

Witteman et al (2019). Female grant applicants are equally successful when peer reviewers assess the science, but not when they assess the scientist. The Lancet, 393, 531-540. (Context: Grant funding).

There was no bias when reviewers evaluated proposals based on science. However, when asked to also evaluate the proposal based on the quality of the researcher, reviewers favored men. This result could reflect sex bias, or it could reflect stronger credentials and accomplishments (on average) among the men. The paper did not assess the role of accomplishments in predicting funding success, so it cannot distinguish between these explanations.

Honorable Mention

Allen-Hermanson, S. (2017). Leaky Pipeline Myths: In Search of Gender Effects on the Job Market

and Early Career Publishing in Philosophy. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. (Context: hiring in philosophy). Main results: women in philosophy are hired at higher rates (relative to the number of job applicants) than are men; and that women need fewer publications to be hired than do men for similar jobs.

Philosophy is not usually considered a social nor natural science, though philosophers have been, more and more, including empirical data in their scholarship. And, of course, philosophy of science is directly related to science. Although I did not include it in my main list above, this paper seemed worth mentioning.

I realize gender bias can be controversial. I would be delighted for you to post a comment, but, before doing so, please read my Guidelines for Engaging in Controversial Discourse. Short version: Keep it civil (no insults or ad hominem, no profanity or sarcasm), brief, and on topic, otherwise I will take your comment down.

---------------------------------------

If you find this essay interesting, feel free to follow me on Twitter, where I routinely discuss this sort of thing. Unfortunately, on Twitter, I cannot take down the comments of those who are uncivil, so, sometimes, things get a little testy. Feel free to disagree, even strongly, but here I can and will enforce civil exchange of ideas.