Alcoholism

Drunk Monkey, Sober Monkey

Brains of alcoholic monkeys contain clues about the biology of addiction.

Posted September 30, 2012

Picture this: you are on an expansive white sand beach, drowsing in the sun, listening to the surf and the calls of seabirds. You sip your drink, set it aside, and tip your beach chair back a bit further. You hear a faint rustling near your towel, and with a sigh, you crack an eye and prop yourself up to have a look—only to see the tail-end of a tawny monkey making a beeline to the nearest palm tree, screeching happily—with your frozen margarita sloshing precariously in the grip of her tiny fist.

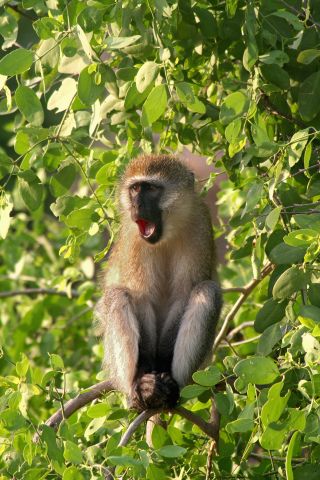

St. Kitts vervet monkeys snag alcoholic drinks on the beach

Welcome to a very typical tourist experience with green vervet monkeys on the beaches of St. Kitts Islands. Like humans, many non-human primates appear to enjoy the intoxicating effects of alcohol—at least, most of them do. Remarkably, the number of monkeys in vervet colonies who drink heavily, drink lightly, or choose to abstain from alcohol resembles the same ratios in humans (in cultures where alcohol use is prevalent). Even teetotaler monkeys who love sweet drinks will turn up their noses if alcohol is added. The clever green vervet monkeys of the St. Kitts Islands have virtually unlimited access to sugary alcoholic beverages; they either lay in wait for the dregs of deserted daquiris, or swoop in to commandeer coladas from unsuspecting beachgoers.

The situation in St. Kitts—individual differences in alcohol preferences occurring “naturally” in a population—has provided a unique opportunity for researchers to examine the biological substrates of susceptibility to alcohol addictionIn a particularly fascinating example of such research, scientists selected monkeys based on individual differences in observed alcohol consumption over a period of two years in St. Kitts. These researchers then examined the dopamine system in the brains of these animals by measuring the distribution and density of a transporter protein called the Dopamine Transporter (DAT); specifically, they compared levels of this protein in alcohol-preferring versus alcohol-abstaining monkeys.

The Dopamine Transporter is a protein that acts by clearing dopamine, the brain’s main “reward” chemical, from the communication space between neurons (the synapse). Essentially, a higher amount of Dopamine Transporter means a lower amount of dopamine is available for signaling; changes in this "clean-up" aspect of the dopamine system are associated with ADHD and depression in humans. Results of the vervet monkey study by Mash et al. demonstrated that monkeys who preferred to drink the most alcohol also had a significantly higher amount of Dopamine Transporter in a brain region called the stratium when compared to their alcohol-avoidant kin—but ONLY when these former-drunk monkeys had been denied access to alcohol for some time. Sure enough, when allowed to drink, the density and distribution of Dopamine Transporter decreased as alcohol-preferring monkeys were allowed to drink; levels of DAT rebounded again during alcohol withdrawal.

Similar alterations in Dopamine Transporter have been observed in human alcoholism, and interestingly, Major Depressive Disorder is also associated with higher availability of Dopamine Transporter. Perhaps this individual difference in the brain dopamine’s system can help explain why many individuals who suffer from depression appear to self-medicate with alcohol, and provide a biological target for pharmacological and cognitive therapy in these harmful disorders.

Mash et al., 1996. Altered dopamine transporter densities in alcohol-preferring vervet monkeys NeuroReport, 7 (1996), pp. 457–462