Addiction

What the Fentanyl? The Straight Dope on a Synthetic Opioid

An interview with medical toxicologist Dr. Ryan Marino.

Posted August 18, 2022 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid with 50 times the potency of heroin.

- Although the high potency of fentanyl makes it a leading cause of drug overdose, it also has important therapeutic uses.

- Myths about fentanyl, like urban legends about aerosolized fentanyl exposure, abound.

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid that has become the number one cause of drug overdoses in the US. To find out why fentanyl has become so dangerous, while also addressing urban legends about aerosolized fentanyl exposure, I sought answers from Dr. Ryan Marino, a medical toxicologist, emergency physician, and addiction medicine specialist at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center and an assistant professor in the departments of emergency medicine and psychiatry at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine.

Joe Pierre: Can you explain what a medical toxicologist is, and the clinical work you do?

Ryan Marino: I'm a medical toxicologist in addition to being an emergency and addiction physician. Toxicology is a large and varied field that seeks to understand how substances affect the human body, from clinical toxicology (e.g. Poison Control Centers) to forensic toxicology to industry and regulation. Medical toxicologists are the bedside physicians who treat what I would call “the poisoned patient,” although this takes many forms, from acute drug effects to addiction and withdrawal, medication toxicity, to industrial exposures, radiation, and bites and stings. If you have a medical problem related to some sort of substance or chemical (“xenobiotic,” the million-dollar umbrella term) then a medical toxicologist is the expert who can treat you.

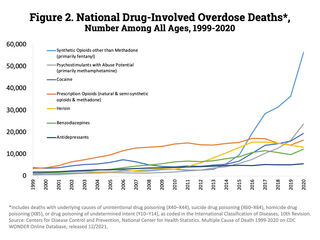

JP: Fentanyl seems to represent a novel danger and significant contributor to the rise in opiate overdose deaths recently, well beyond those attributed to heroin, another synthetic opioid that has been around for more than a century and was even sold and marketed by pharmaceutical companies. Why has fentanyl and its analogs become so dangerous?

RM: Fentanyl is neither good nor bad; it's just another xenobiotic molecule. While fentanyl is certainly the driver of record opioid overdoses, it's also one of the most valuable therapeutic medications used in medical facilities around the world. What makes it particularly dangerous in nonmedical use—or at least unregulated and unsupervised—is its potency. Compared to morphine, fentanyl has approximately 100 times the potency and 50 times the potency of heroin. In terms of street drugs, heroin was classically ~50 percent pure heroin (and 50 percent cutting agents). When fentanyl entered the drug market it was sold as 1 percent pure fentanyl to achieve the same effects. Because drugs are illegal they're sold on the black market using limited equipment and without oversight or regulation; errors in percent purity can happen rather easily. When it comes to fentanyl, a 2 percent pure product is a double dose. These minute errors were less significant with drugs like heroin.

JP: There’s a long history of mixing heroin with cocaine for recreational use—a deliberate combination known as a “speedball”—but fentanyl is finding its way into drugs like methamphetamines or MDMA (ecstasy) seemingly without users being aware of it. If this isn’t a consumer-driven phenomenon, why is this happening?

For the same reason—potency—we're now even seeing trace contamination from fentanyl on other black market drugs, as simple as residue from using the same equipment, causing opioid overdoses for people using things like cocaine and amphetamines. Speedballs are definitely still a thing even in the age of fentanyl, but the fentanyl overdoses that are now happening in association with stimulant use seem to be unintentional. This is entirely preventable. We used to see the same kind of harm from prescription and over-the-counter drugs (and even food) without regulation. Because black market drugs are not usually afforded the same regulatory processes, it's easy for cross-contamination to occur. It’s not even just the fentanyl; other compounds in the black market drug supply can be quite toxic. A regulated drug supply could prevent a lot of overdoses and save a lot of lives.

JP: There have been scores of reports of police and paramedics coming into contact with fentanyl and developing symptoms suggestive of acute exposure as if it was absorbed through skin contact or through inhalation. But fentanyl isn’t absorbed through the skin or aerosolized to any degree. What kind of success are you and others having to counter that misinformation?

RM: It’s hard because I have to speculate on what's going on and why. Is it an innocent phenomenon where people are being harmed by misinformation that's fed to them or is it something more sinister that's being weaponized against people who use drugs and to increase resources for drug criminalization? I can say definitively that none of these stories has been a fentanyl (or other opioid) overdose. Fentanyl and related compounds are quite easy to detect even in insignificant amounts in the human body, and fentanyl overdoses have very characteristic and well-defined features. None of these stories has ever met the criteria for an overdose or shown fentanyl detected in the person involved. If we were talking about plutonium exposure, or really almost anything else, there would be a baseline level of skepticism that's absent from these stories. While the reports show no sign of slowing, I'm encouraged by the large amount of support that has materialized for holding media and law enforcement to higher standards of accountability when it comes to drugs. Drug misinformation is so rampant and involves so much more than fentanyl, and it affects us all whether we use drugs or not.

JP: Why is there a big gap between what the experts tell us and the misinformation being promoted? I see these reports as evidence of a psychogenic reaction that’s rooted in fear and expectation, while you and others like to invoke the nocebo effect. But West Virginia passed legislation imposing penalties for exposing government representatives to fentanyl or other drugs. How do criminalization and politics relate to the bigger picture?

RM: I do think there are multiple things happening with this phenomenon. I think some people are reacting to misinformation à la the nocebo effect and videos like the dollar bill woman and the San Diego sheriff deputy seem to support this. But fentanyl has occupied a space in our social consciousness as some sort of boogeyman and I hear from people who swear to me that someone they knew had a “fentanyl exposure” event. That's the main reason I go out of my way to reiterate that it's a valuable therapeutic medicine and is used very safely all the time. But it’s even more concerning to me that it has taken hold in terms of funding allocation, legislation, and criminal penalties. Multiple people have been incarcerated for exposing law enforcement to fentanyl and in a society based on the rule of law, it should disturb everyone that people are being charged with and punished for an imaginary crime.

JP: In April 2021, you submitted a letter to Congress arguing against class-wide scheduling for fentanyl analogs. Can you explain your concerns about making fentanyl analogs Schedule I drugs?

RM: First, criminalization does not work. The US DEA Scheduling system isn't based on any real science and not only is it based on falsehoods (and a lot of racism) but it doesn’t even have any logical basis behind it whatsoever. We’ve been trying to criminalize certain drugs and certain people for a century and yet we're breaking new records for overdoses, deaths, and preventable harms every year. Above all, I would like politicians to stop making things worse for people who use drugs and the people who care about them.

But I do have specific concerns about this legislation that is still active and will be up for a vote again in the next few months. As I've said repeatedly, fentanyl is a valuable therapeutic and there are fentanyl analogs that we use medically and are also incredibly valuable for their own different properties. Even carfentanil has an approved therapeutic use. Some of the fentanyl analogs on this list actually antagonize opioid effects and could prove to be important antidotes for poisoning from opioids like fentanyl. And a significant portion of them, in addition to the ones yet to be discovered, have not been studied. This kind of ban would limit our ability to even learn how these drugs work and limit our ability to advance our knowledge and our practice.