Politics

Can Polarized American Politics Find the Middle Way?

Fighting the "binary bias" with cognitive flexibility.

Posted October 15, 2019

E Pluribus Unum ("out of many, one")

—the motto of the United States of America

These days, it often seems like the U.S. has become mired in acrimonious, polarized, political debate with no way to move forward as a unified country. The view from social media suggests that the potential for mutual understanding is routinely foiled by toxic interactions sabotaged by the online mechanics of anonymity, filter bubbles, echo chambers, and Russian meddling intent on sowing discord. Face-to-face interactions, when they do occur, often aren’t much better.

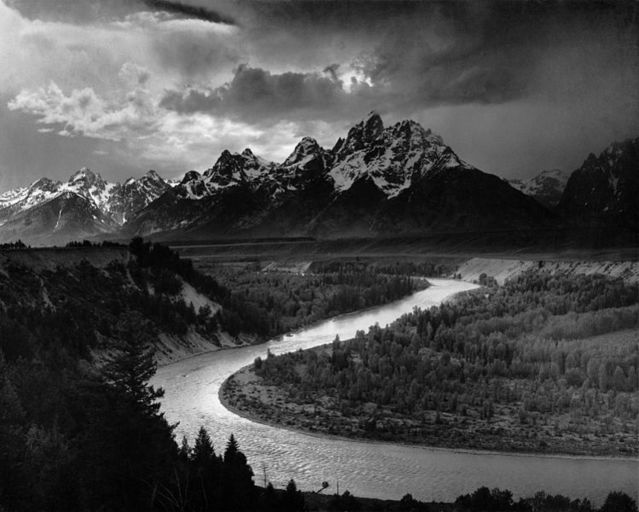

America’s toxic polarization can be explained in psychological terms as having collectively fallen into the trap of a classic cognitive distortion called “all-or-none thinking,” whereby we falsely view the world as either black or white rather than acknowledging nuances within grey areas.

Recent research has found robust evidence that our brains often fail to weigh the evidence that would allow us to properly integrate information, due to a “binary bias” that instead favors processing continuous data into separate, dichotomous categories.1 Like other cognitive biases, this kind of unconscious thinking probably evolved as an efficient shortcut but can get us into trouble when it leads to narrow-minded decision-making based on entrenched beliefs.

Nowhere is a binary bias more apparent than the literal black and white dichotomy of race in the U.S. As a person of mixed-race heritage, President Obama had potential to be a unifying figure, but few could resist confining him within a single race check-box based on opposing agendas that either claimed him or marginalized him according to the “one-drop rule.” This year’s Catholic Covington fiasco served as a kind of Rorschach Test, with most of us taking one of two sides in what was, in reality, a three-way “Mexican standoff” with far more complexity than was generally acknowledged.

We approach the other hot-button political topics of our day in much the same fashion. The national conversation around abortion, immigration, and gun control is typically framed in terms of polar opposites. Instead of seeking middle ground, the dominant political strategy now consists of trying to shift the Overton window by advocating extremes and using windows of party majority advantage to railroad legislation through Congress and to appoint partisan Supreme Court Justices.

Some have claimed that cognitive biases are more prevalent among Trump supporters, consistent with the so-called “rigidity of the right” hypothesis. But a more accurate and productive perspective is that cognitive biases are normal fallibilities of all human brains, regardless of political orientation.

Recent research by social psychologist Jan-Willem van Prooijen has determined that certain cognitive biases, like black-and-white thinking, are shared at both extremes of the political divide.2 The “cognitive simplicity” of black-and-white thinking, van Prooijen claims, often leads to overconfidence in our political beliefs.

What can we do to gain perspective beyond this inherent cognitive rigidity? The answer is hardly new. With its roots in early Buddhism, the philosophical prescription to seek “the Middle Way” has since been reflected in the complementary dualism of the I Ching’s “yin and yang” and in the more modern Western “thesis, antithesis, synthesis” approach of Hegelian dialectic.

Today, finding a middle ground for the common good is a philosophy that’s familiar to us all, even if it’s often hard to follow in our daily lives. Most married people know that the secret to happiness is compromise, but it requires that we not think of compromise as a mutual loss.

A national survey conducted by the Hidden Tribes of America project found that an “exhausted majority”—as many as two-thirds of the U.S. population—are fed up with political polarization fueled by the voices of relative extremists and instead believe in seeking common ground. Organized by a group calling itself More in Common, the Hidden Tribes project aims to encourage “flexible thinking” in order to “restore a sense of respect and unity” to the country. According to its mission statement, More in Common aims to “build more united, inclusive, and resilient societies in which people believe that what they have in common is greater than what divides them.”

In a somewhat similar vein, the concept of “intellectual humility”—the acknowledgment that our personal convictions might be wrong—has gained recent traction in psychology, with potential applications to religious tolerance, scientific discourse, and politics alike. Of note, Duke psychologist Mark Leary’s research on intellectual humility found no evidence to support the “rigidity of the right” hypothesis.3 Intellectual humility is equally present and equally lacking among both liberals and conservatives.

Whatever we choose to call it—open-mindedness, intellectual humility, or my preferred term, “cognitive flexibility”—the psychological antidote to getting stuck in black-and-white thinking involves first being aware of our cognitive biases and then making an effort to see beyond them. As a famous Zen koan tells us, we have to first “empty our teacups” in order to make room to expand our minds.

With that willingness established, belief convictions should be held and expressed as probabilities, not absolutes. This is a basic principle in cognitive behavioral therapy, which seeks to challenge and modify false beliefs and cognitive distortions.

Intellectual humility must not be confused with anti-intellectualism, which has been blamed for the downfall of the country at least as far back as Richard Hofstadter in 1964 and Isaac Asimov in 1980. Both Hofstadter and Asimov attributed anti-intellectualism to the democratization of knowledge in America, a process that has significantly accelerated with the internet since their time. This has brought us into the now-familiar, epistemological quagmire which claims that “both sides” and “alternative truths” are equally valid and that truth is unknowable.

Such nihilistic false equivalence is often used to argue that we’re right and others are wrong, keeping us closed off to other perspectives and opportunities to learn, leaving us vulnerable to confirmation bias and the Dunning-Kruger effect, and fueling black-and-white thinking.

Whereas anti-intellectualism is a form of unwarranted arrogance that claims that uninformed personal opinion should be considered on equal footing as the knowledge of qualified experts, intellectual humility has been defined as the “virtuous mean lying somewhere between the vice of intellectual arrogance (claiming to know more than is merited) and intellectual diffidence (claiming to know less than is merited).”4 While scientists and other experts are by no means immune to intellectual arrogance, intellectual humility is built into the scientific method, where revising conclusions in light of new evidence is part of the search for truth. Belief modification grounded in cognitive flexibility is a strength of science that distinguishes it from dogma.

Of course, not all debates about the right way forward for the country have clear answers in science. And much of our current political divide is based not so much on disputable facts as it is on values, moralities, and, as University of Maryland professor Lilliana Mason’s work has recently shown, identities.

The more we’re boxed into dichotomous categories of tribes and teams, the more we dig our heels into our respective dogmas. To deviate means admitting that I’m wrong, not just my beliefs. That idea, that we are our beliefs, and that changing them is a weakness that equates to losing ourselves, is something we would do well to get away from.

In politics, that change has to include our leaders. From Donald Trump and Barrack Obama to Abe Lincoln, politicians have long been taken to task for the unforgivable crime of “flip-flopping” or “dithering.” Changing one’s mind in light of new information can be deadly for politicians, but it doesn’t have to be this way. After all, while cognitive flexibility involves taking a broad range of perspectives into account and adapting to change, it’s not the same as indecisiveness. Making a reasoned assessment of risks and benefits doesn’t preclude swift, decisive action when it’s called for.

Beyond cultivating cognitive flexibility on a personal level and hoping that our leaders do the same, a number of more radical proposals could be implemented within American culture that might help free us from the paralysis of toxic polarization. We could teach cognitive flexibility within core elementary and high school curricula, with students learning about the scientific method, cognitive biases, how to navigate the morass of online information (see the University of Washington’s “Calling Bullshit: Data Reasoning in a Digital World”), and the basic premise that it’s OK to admit that you’re wrong.

We could abandon traditional debates in favor of “turncoat debating,” in which individuals are graded on their ability to present and synthesize opposing views, not only at the level of academic debate clubs but also in political primaries. We could follow the lead of Maine and other municipalities and broadly adopt ranked-choice voting, which increases the chances of elections being won by moderate politicians who can appeal to voters across party lines.

We could rewrite our popular cultural myths that have become dominated by caricatured battles between good and evil, returning to more nuanced narratives. And we could strive towards swinging the pendulum back towards the kind of civility and spirit of compromise embraced by our Founding Fathers and the kind of mutual empathy that helped us steer the country through the Cold War and the Civil Rights era.

But of course, that’s all easier said than done. In 2010, No Labels started as a political organization with a goal of “activating citizens and organizing leaders around a new politics of problem-solving” and the non-partisan slogan, “not left, not right, forward.” In 2017, it helped to create the House Problem Solvers Caucus and recently advocated for requiring bipartisan support in elections for the Speaker of the House so that centrist proposals would get more of a voice in Congress.

But enthusiasm for the group and its spirit has been tepid, with critics claiming that it “ignores reality” and has accomplished little. New York Times columnist Frank Rich called No Labels a “bipartisan racket” and argued that “the notion that civility and nominal bipartisanship would accomplish any of the heavy lifting required to rebuild America is childish magical thinking, and, worse, a mindless distraction from the real work before the nation.”

Heavy lifting indeed. While compromise may have been a key factor in our evolutionary success, it still conflicts with our other tribal instincts, like black-and-white thinking, which are tightly sewn into our neuronal fabric. Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel famously argued, “We must take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.”

Just so, in the present political divide staged as a conflict of moral righteousness between “good” and “evil” where the pressure to be immovable in our convictions is pervasive and strong, few want to hear a “kumbaya” message of compromise. Most of us get stuck on, “If I’m right, and they’re wrong, why try to meet in the middle?”

There are two answers. First, that’s what “the other side” is thinking too. One of us, or both of us, could be wrong—that’s intellectual humility. And second, we have to start from a place of empathy for our ideological opposites—not the same as agreement or apologism—if we ever hope to change hearts and minds, bringing us closer to a place of mutual understanding and meaningful change. That’s psychotherapy 101.

“Can we all just get along?” If Rodney King’s timeless rhetorical question can be rightly accused of naiveté, it’s because of the realism that lies at the heart of the familiar joke, “How many psychiatrists does it take to screw it a lightbulb? Just one, but the lightbulb has to want to change.”

There’s no chance of finding the middle way in politics if there’s no commitment from both sides of the partisan divide to move forward together. As in marriage, if there’s no commitment, there’s always divorce. But for our country, that would mean mission accomplished for those with vested interests in fomenting American discord and an end to the United States.

For those that don’t want divorce or compromise, there’s always continuing down our current path of dysfunction. But if we do that, we shouldn’t expect anything other than more of the same.

For more on the psychology of a divided America:

References

1. Fisher M, Keil FC. The binary bias: A systematic distortion in the integration of information. Psychological Science 2018; 29:1846-1858.

2. van Prooijen J, Krouwel APM. Psychological features of extreme political ideologies. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2019 (in press). https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0963721418817755

3. Leary MP, Diebels KJ, Davisson EK, et al. Cognitive and interpersonal features of intellectual humility. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2017; 43:793-813.

4. Samuelson PL, Jarvinen MH, Paulus TB, et al. Implicit theories of intellectual virtues and vices: A focus on intellectual humility. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2015; 5:389-406.