Genetics

Is Education Written in Genes?

Genes are relevant but can’t say how long or why someone will stay in school.

Posted April 7, 2022 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- A study of 3 million people follows decades of research on educational attainment’s genetic background.

- Genetically related people tend to have somewhat similar attainment levels.

- But no genes specifically influence an individual’s attainment or allow accurately predicting it.

- Genes’ roles are too complex to say anything meaningful about individual people.

Among the key questions of psychology is the nature versus nurture problem. Are we born with our characteristics or do we pick them up as we go?

This is no longer a merely philosophical debate. Over the last decades, scientists have studied millions of people with different degrees of genetic relatedness. Comparing them in hundreds of traits has established some of the most robust findings in psychology.

Relatives tend to be more similar than strangers

For example, insomuch as genetically identical twins are more similar than non-identical twins, genes must somehow matter. The same logic extends to other kinds of relatives.

From this work, we know beyond a reasonable doubt that:

- Genetically similar people tend to be more similar in any measurable trait, from height and disease to personality traits and educational attainment.

- But because even genetically identical twins can be quite different, life experiences must also have a say.

No trait is genetically determined, but only partly heritable. But exactly how much do genes versus experiences matter? Establishing this has been tricky because the two cannot be separated. For example, genetically similar people like identical twins tend to experience similar things, because partly heritable traits play a role in which environments they create for themselves—that is, genes “leak” into the environment.

For most psychological traits, twin comparisons suggest that about 30 to 60 percent of differences between people might be due to their genetic differences. The same goes for educational attainment. But these estimates could be biased, possibly quite strongly, so they need to be confirmed in other research designs.

Hands-on with the genome

Over the last two decades, it has become ever easier to measure specific DNA variations (alleles). It is now possible to map individuals’ alleles in millions of locations along their chromosomes and see whether one versus another allele tends to go with higher or lower levels of any measurable trait. Some call it the "DNA revolution."

As a result, researchers now study whether genetic similarity among non-relatives tracks their trait similarity. This provides another way to estimate how much genes matter, but also which specific genes may be relevant for which specific traits.

One trait (or life outcome) has received outsized attention in this work because it is easy to measure and has many consequences in Western people’s lives: educational attainment, often measured as the number of years that people receive formal education.

Of course, no one thinks that genes, which define protein assembly in cells, directly influence how long people go to school. Instead, genes are expected to influence any number of cognitive and bodily abilities, personality traits, or mental and physical health aspects relevant to educational outcomes.

Recently, Aysu Okbay and her colleagues published the largest ever genetic study on educational attainment. It included over 3 million people whose genetic differences had been mapped in over 10 million locations along their chromosomes.

Their findings confirmed what most already suspected: genes are undeniably relevant, but their roles are too complex to say much more than that.

Thousands of genes do something

Nearly 4,000 locations along the DNA were singled out to have statistically reliable links with educational attainment, but each link was very weak. On average, having one more copy of an education-increasing allele meant that people went to school for seven more days.

Counting how many copies of these education-increasing alleles people carried, researchers created a “polygenic” score for each individual, showing their genetic probability for longer schooling. These scores correlated up to 0.30 with people’s actual years of education.

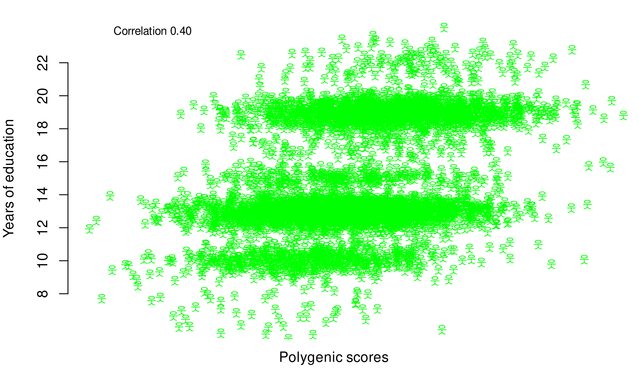

Researchers then expanded the polygenic scores to include thousands of additional alleles that could not be decisively linked to attainment but could still have tiny associations with it. These expanded scores correlated with years of education more strongly, up to 0.40.

This shows that many, many thousands of locations in the DNA must somehow matter for education. Specifically, squaring the 0.40 correlation to get the proportion of variance that polygenic scores and actual years of education shared says this:

Sixteen percent of why people differ in their length of schooling can be ascribed to the small effects of many thousands of alleles.

Authors were quick to point out that this statistical association was too weak to meaningfully predict individual people’s educational levels from their polygenic scores, nearly all scores could be found at nearly all levels of education.

Here’s very roughly what this association could look like:

Also, the education’s polygenetic scores had statistical links with several common health conditions like heart issues, diabetes, and depression. Previous work has found many more links with various health conditions and personality traits, not to mention cognitive skills.

This is very important, meaning that there are no one-to-one relationships between genes and people’s traits. Most genes that create differences between people don’t specialize in shaping specific traits or outcomes but somehow manifest broadly across our minds and bodies.

Here’s what this probably means.

Partly genetic but without genes

It is unlikely that all of these thousands of genetic variations that were statistically linked with education among 3 million people were equally relevant for each and every individual’s attainment. Instead, the large number of small statistical associations probably means that the same education can be achieved through very many different combinations of traits and genes linked with these traits.

For example, any number of traits can help someone towards a college degree, including a range of cognitive or bodily skills, working hard, weaseling, or numerous other personality traits. Likewise, any number of traits can be obstacles, such as physical or mental health issues, poor social skills, or low academic self-esteem.

Each of these traits can be associated with some combination of genes in some individuals, which then appear weakly linked with educational level in very large groups of people. But because the same educational level can result from many different trait combinations, most of these statistical links are not actually relevant for most people's ways of getting on at school.

This can also explain why polygenic scores created from education-allele links among people with European ancestry poorly predicted attainment among people with non-European ancestry. People with different backgrounds can achieve the same level of education through different traits and whichever genes are associated with these traits.

Genes and environment really are inseparable

A subset of participants included parents and their children. Not surprisingly, parents’ polygenetic scores for education were also somewhat linked with their children’s educational level—again, educational attainment is partly heritable. But here’s the interesting part: even the education-increasing alleles that parents had not passed on to their children somehow mattered for children’s attainment.

Some of the reasons that genes are correlated with educational attainment are not because genes directly influence education, but because parent-provided environment matters for their kid's education, and this environment also happens to come with certain genes being passed along to the kids.

Useful for research, but not for individuals

Even all genes combined are only part of why some people go further in education than others because education—like any other trait—is only partly heritable. Also, it is now quite clear that there are no genes specifically for education. Many different traits and their associated genes can lead to the same educational outcomes, and genes also work by shaping the environment.

Polygenic scores can be useful for research with large samples, where predicting or understanding the attainment of individual people is less important. For example, they have been used to show that selective schools don’t provide better average educational outcomes than ordinary schools, once children who are comparable in their genetic probability for higher education are compared. Selective schools tend to attract higher-achieving students, but they can be good for some, bad for others, and hence not benefit students on average.

Polygenic scores may also help to show which interventions can actually improve average educational outcomes and for whom, beyond people naturally finding ways to use environments to their advantage. For example, kids from more educated families may often manage to secure better treatment even within the same environment, so those who appear to benefit from interventions may often be different to start with. Polygenic scores can capture such effects and help to statistically mitigate them.

But the gene-education links mean very little for individual people. Children’s future educational levels cannot be read from their genes with a meaningful level of accuracy. Nor can genes explain why some people go to school for longer than others, because of the intractable number of ways that genes can matter in any given individual. The idea of genetically personalized education is unlikely to be practical—even if we actually wanted it, for some reason.

There really is no genetic determinism for educational attainment, the very best genetic research suggests as much.

References

Okbay, A., Wu, Y., Wang, N., Jayashankar, H., Bennett, M., Nehzati, S. M., Sidorenko, J., Kweon, H., Goldman, G., Gjorgjieva, T., Jiang, Y., Hicks, B., Tian, C., Hinds, D. A., Ahlskog, R., Magnusson, P. K. E., Oskarsson, S., Hayward, C., Campbell, A., … Young, A. I. (2022). Polygenic prediction of educational attainment within and between families from genome-wide association analyses in 3 million individuals. Nature Genetics, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-022-01016-z