Career

How to Get More Students to Participate in Programs

Asking students to sign up can be a bigger obstacle than you think.

Posted October 4, 2018

Congratulations on creating an amazing new success program that will help disadvantaged students navigate the Daedalian labyrinth that is college and emerge with a life-changing degree in hand! It has taken you countless hours, numerous committee meetings, and two parts sweat to one part tears. Students have been duly informed—a postcard in every mailbox, an e-mail (or three) in every inbox, and a poster on every bulletin board—and now it’s up to them to sign up for this transformative experience.

But will they?

Whenever we launch a new program to help our students achieve their goals, it’s always worth considering the benefits of automatic or opt-out enrollment. Although automatic enrollment won’t fit every scenario, we often default to manual enrollment—students have to sign up to be part of our program or to receive supports—without even thinking about it. Requiring students to enroll guarantees that no one gets something that they didn’t ask for. Manual enrollment can also promote efficiency by ensuring that services are not provided to students for whom they are either unwanted or unnecessary. But asking students to sign up can have surprising impacts on participation, especially for those in greatest need of your support.

Automatic versus manual enrollment

A recent study encapsulates the barriers that arise with manual enrollment. A group of researchers wanted to know if requiring parents to sign up for text message alerts about their child’s academic performance—as opposed to sending alerts automatically—would make a difference in whether parents made use of the service. This study included nearly 7,000 parents from 12 middle and high schools in Washington D.C. that served almost exclusively African American and Hispanic children. All parents were sent a text message with instructions about how to receive further alerts.

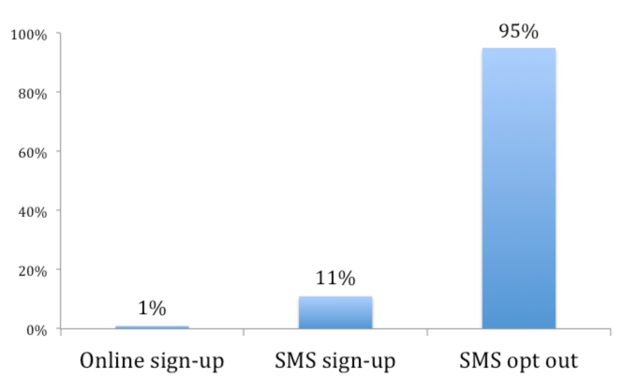

Before reading on, take a moment to ask yourself: What percentage of parents do you think would sign up for this program? Likewise, what percentage of parents would opt out of the program if they were automatically enrolled? Now that you’ve pondered that, here are the results:

When parents had to sign up online, fewer than 1% did so. Only 11% of parents signed up when they needed to respond to that first text message with “Start” in order to receive alerts. Under automatic enrollment, however, parents received the text alerts unless they replied with “Stop.” In this condition, 95% of parents used the service for the entire school year. More importantly, children whose parents were automatically enrolled in text alerts saw a 3% increase in their GPAs and a 10% reduction in class failures, whereas the intervention had no effect on children’s outcomes when parents were asked to sign up.

How accurate were your guesses about parental participation? If you were far off, don’t fret because you’re not alone. As a follow-up, the researchers asked 130 principals, superintendents, and other education professionals who came through the Harvard Graduate School of Education to predict the results of the study. On average, they thought that 40-50% of parents would sign up for text alerts, well off of the actual figure of 1-11%. Moreover, they believed that over a third of parents would opt out of automatic enrollment, much higher than the actual rate of 5%. Thus, even experts in their field grossly overestimate the efficacy of manual enrollment and underestimate the efficacy of automatic enrollment, misperceptions that may affect how they design their own student success programs.

This study, in which opting parents into the text alert program improved their children’s educational outcomes, is just one example of when automatic enrollment may be more justified than manual enrollment. These findings also point us to two key elements to consider when deciding whether to use automatic enrollment: access and equity.

How automatic enrollment promotes access

How did automatically enrolling parents in the text alert system promote access any more or less than letting parents sign up? We must realize that when people don’t sign up for a program, it doesn’t necessarily mean that they don’t want it. People fail to sign up for a number of reasons—they’re too busy, they forgot, they don’t understand the sign-up process—none of which involve an active choice. As evidenced by the parent study, any burden presented by the sign-up process, like having to access a website, needing a password, etc., can disproportionately dissuade behavior. We know from the automatic enrollment condition, however, that only 5% of parents actively declared that they did not want text alerts. Thus, when automatic enrollment leads to uptake rates approaching 100%, and manual enrollment omits four-fifths of your target population, the sign-up process becomes a barrier that unfairly limits access.

A counterargument is that automatic enrollment makes a choice on other people’s behalf that impinges on their autonomy. To address this concern, automatic enrollment must always coincide with a simple and easy way to opt out. In this case, all parents had to do was reply “Stop”—the same amount of effort required to sign up by texting “Start”—yet only 5% of parents did so. Perhaps more importantly, manual enrollment doesn’t preserve autonomy in the way we assume it does. When your choice between automatic and manual enrollment can lead to nearly everybody or nearly nobody receiving a valuable service, you must acknowledge that, either way:

You are making a decision on behalf of the people that you want to help about whether they will participate in your program.

How automatic enrollment promotes equity

For the most part, parents who didn’t sign up for the text alerts were the same ones who couldn’t participate in other programs for their children. Moreover, these parents’ children had lower average GPAs and were more likely to fail a course before the intervention started, exactly the outcomes that were improved by the text alerts. Manual enrollment, therefore, proved to be a barrier to helping specifically those parents and children who needed it most. In another telling example, one-half to three-quarters of new hires don’t sign up for their 401(k) benefits within their first 6 months, as opposed to the more than 85% of new employees who remain enrolled in this retirement program at 6 months following automatic enrollment. More importantly, employees who are younger, earn lower salaries, and are either African American or Hispanic are more likely to delay signing up for their 401(k), or never sign up at all. Again, the sign-up process acts as a barrier, but more so for those who are most vulnerable.

When we closely examine the students who fail to sign up for our programs, it often reflects traditional lines of disadvantage: first-generation students, students from low-income backgrounds, students struggling academically, and students with less social capital are the ones who don’t show up. This “rich get richer” effect undermines the purpose of any program trying to help at-risk students succeed and close achievement gaps. But inequity is eliminated the nearer that our participation rates get to 100%, which is exactly what automatic enrollment can do. In any instance where you observe systematic inequities among the students who engage in a support program, it is well worth considering whether automatic enrollment can bridge those gaps.

Why is automatic enrollment so effective?

Often when researchers discuss automatic enrollment, they frame its benefits in terms of the status quo bias: people generally prefer to leave things as they are unless compelled to make a change. So if we haven’t started a 401(k) and there’s no immediate problem that will be solved by having one, we have little reason to sign up. With automatic enrollment, on the other hand, if we’re given a 401(k) and cancelling it won’t meet an immediate need, we keep it. As Yale Professor of Finance James Choi and his colleagues argue, we follow “the path of least resistance.”

But I believe an even more important ingredient to automatic enrollment is that it signifies a recommendation, one that is all the more influential when coming from a trusted, expert source. If your child’s school automatically enrolls everybody in the text alert system, it implicitly tells you that the school thinks these alerts are important. It also establishes a norm that all of the other parents are getting these texts about their child, motivating you to do so as well. This is why automatic enrollment is a “nudge”: it doesn’t just exploit the status quo bias, but it also tacitly recommends a course of action, which can be very powerful in increasing uptake and persistence.

Using automatic enrollment at your institution

I hope by now you’re convinced of the benefits of automatic enrollment for promoting access and equity, but it may be challenging to figure out how you can use this strategy for your programs. The first thing to realize is that automatic enrollment is more common on campus than you think. When students enroll at your institution, do you give them an email address? Are they assigned to an advisor? Are they credentialed to use an online portal? While getting students to actively engage with these resources requires ongoing effort, automatic enrollment propels usage outside of our awareness because we don’t even think any more about how it would compare to manual enrollment.

Second, keep in mind that automatic enrollment isn’t binding…and it doesn’t need to be in order to be effective. For example, if you want more incoming students to use Career Services, why not automatically make them an appointment that fits their class schedule? This would convey the norm that new students should be visiting the Career Center and remove the burden of signing up that could disproportionately affect certain populations. Yes, some students would cancel, and more would simply not show up, but a message about the importance of early career planning could still get through even if the desired behavior doesn’t follow. In a similar vein, instead of asking students to sign up for a new success program, just tell them that they’ve been selected into it and how it works. For the same effort on your part (e.g., writing an email), you’ve now implicitly recommended your new program to students and removed unnecessary barriers to participation. While these strategies likely come at the cost of efficiency, they may more than make up for it in terms of access and equity.

Conclusion

A knee-jerk reaction when nobody signs up for our programs is that students are unengaged; why wouldn’t they want free help to get through college? But there are myriad reasons why when you build it, they don’t come, few of which are that students neither want nor need your help. Automatic enrollment should only be applied, of course, with students’ best interests in mind, which is why both access and equity are good barometers for when you should use this strategy. But whenever possible, I urge you to strongly consider how automatic enrollment could help you help more of your students to achieve their educational and personal goals.

References

Bergman, P., Lasky-Fink J., & Rogers, T. (2018). Simplification and defaults affect adoption and impact of technology, but decision makers do not realize this. Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Research Working Paper Series.

Choi, J. J., Laibson, D., Madrian, B. C., & Metrick, A. (2005). Saving for retirement on the path of least resistance. Rodney L. White Center for Financial Research Working Papers - 9.