Health

The Current View of Microbes and Mental Health

Findings demonstrate potential for microbiome therapy in clinical psychology.

Posted June 27, 2022 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Mental health is influenced by many aspects of physical health; microbiota-brain interactions are among them.

- Alterations in diversity, composition, and function of gut microbes influence anxiety and depressive symptoms.

- Microbiome-related biomarkers may help better match individuals with specific treatment options.

By Jane A. Foster, Ph.D.

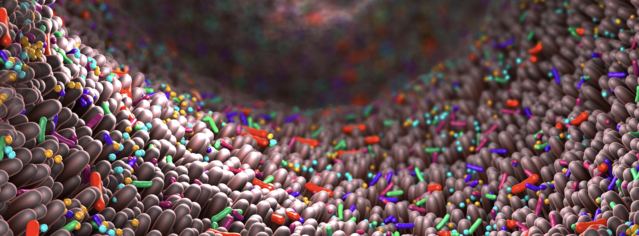

Trillions of microbes living in our guts play an essential role in health. Remarkably, crosstalk between gut microbes and the body influences brain and behaviour. Microbes include viruses, fungi, parasites, protozoa, and bacteria—but at this time, most research has studied gut bacteria in relationship to mental health. Curiosity in this fast-moving area is fueled by media attention related to recent advances in our understanding. And the potential of psychobiotics—that is, treatment with live bacteria (probiotics) that benefit mental health—is of great interest.

As a neuroscientist and active microbiome researcher for 15 years, it is exciting to see microbiota-brain research gain momentum. For me and others, interest in studying the microbiome was sparked by a scientific report published in 2004 by Sudo and colleagues showing that mice raised in sterile conditions (germ-free mice lacking all microbes) had an exaggerated physiological reaction to stress. It was clear then that stress, and how the body responds to stress, have a direct impact on mental health.

Studies considering the link between microbes and behaviour, particularly stress-related behaviours such as seen in anxiety and depression, were soon to follow. These early preclinical studies across different labs in different countries further established a link between gut microbiota and anxiety-like behaviour. While initially only a handful of neuroscientists saw value in studying the microbiota-brain axis, the engagement of the broader neuroscience community has expanded in the past decade. What’s more, clinical evidence now shows an important role of the microbiota-brain axis in psychology and psychiatry.

Based on a strong foundation of preclinical studies, mounting clinical evidence demonstrates that microbiota-brain signaling is an important factor in anxiety and depression. Several studies have reported differences in the diversity, composition, and function of the gut microbes in individuals diagnosed with major depression and anxiety disorders compared to healthy individuals. Moreover, changes in particular microbes are associated with increased depressive and anxiety symptoms, sleep disorders, and reward processing.

Probiotics are live bacteria that, when ingested, confer mental health benefits through interactions with resident gut bacteria. A collection of studies have administered probiotics to healthy people, most often for four weeks, and demonstrated improved mood, reduced levels of stress hormones, and reduced anxiety and depressive symptoms. Interestingly, studies using imaging tools have shown an association between the composition of a person’s gut microbes and brain function including emotional responses.

But how do gut microbes communicate with the brain, and how might that link to mental health? For clarity, we need to go back to the basics, the gut-brain axis. The gut-brain axis has been studied for more than 100 years, yet only in the past couple of decades has the microbiome and its importance to the gut-brain axis been recognized. Researchers now refer to the “microbiota-gut-brain axis" and have identified pathways by which gut microbiota communicate with the brain.

- Gut microbes activate neural pathways to communicate with the brain.

- Gut microbes also regulate the immune system and influence immune-to-brain communication pathways that are important to mood.

- Alterations in gut microbes may lead to increased inflammation and contribute to anxiety and depression.

Gut microbes contribute to a healthy metabolism. Specific types of bacteria can ferment fibre in our diet to produce a wide variety of metabolites that can act locally to facilitate good gut health and can enter the bloodstream to act remotely on other tissues, including the brain. Imbalances in these metabolic pathways can also contribute to anxiety and depression. Certainly, clinical studies have shown altered profiles in microbiome-related and host-related metabolites in depressed individuals.

Advances in our understanding in this area have been incremental; however, state of art approaches used in current microbiome studies provide both compositional and functional readouts of the microbiome that will help move this field forward to better understand in more mechanistic detail how changes in microbiota-to-brain signaling contribute to clinical features in anxiety and depression. Strategies to harness the potential of microbiome-based biomarkers to better match patients to available treatments, as well as the development of microbiome-targeted therapies to improve clinical outcomes are promising.

Where do we go from here? Brain research has lagged behind other research areas such as metabolic disorders and cancer immunotherapy, areas that have seen major clinically impactful discoveries related to the microbiome in recent years.

It is important to point out that microbiota-brain communication is continually active and part of healthy body homeostasis. It is not a static bystander but rather a dynamic and interactive partner.

Compared to a decade ago, studies investigating the microbiome and mental health are now at the forefront of biomedical research. The shift from a brain-centric approach to a more holistic one in psychiatric healthcare is essential to paving the way to discoveries that increase our ability to leverage the microbiome to promote better outcomes in the clinic and in daily life.

The potential benefit of microbiota-targeted therapeutics to treat brain-related disorders has led to an expansion of companies targeting the gut-brain axis. In addition to probiotics and prebiotics, companies are developing live biotherapeutic products to be used, while others are focusing on the molecules produced by microbes as potential therapeutics.

The potential for novel therapeutic strategies in a more holistic framework opens up the conversation to consider the mental health impact of physical health, as well as diet and other lifestyle factors. Notably, nutritional psychiatry as a research entity is expanding and gaining more recognition. A more holistic view, across psychiatry and psychology, paired with greater acceptance of the importance of the microbiome to mental health by the broader medical community, is a necessary next step.

References

Sudo, N., Chida, Y., Aiba, Y., Sonoda, J., Oyama, N., Yu, X.N., Kubo, C., and Koga, Y. (2004). Postnatal microbial colonization programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system for stress response in mice. J Physiol 558, 263-275.

Tillisch, K., Mayer, E.A., Gupta, A., Gill, Z., Brazeilles, R., Le Neve, B., van Hylckama Vlieg, J.E.T., Guyonnet, D., Derrien, M., and Labus, J.S. (2017). Brain Structure and Response to Emotional Stimuli as Related to Gut Microbial Profiles in Healthy Women. Psychosom Med 79, 905-913.

Valles-Colomer, M., Falony, G., Darzi, Y., Tigchelaar, E.F., Wang, J., Tito, R.Y., Schiweck, C., Kurilshikov, A., Joossens, M., Wijmenga, C., Claes, S., Van Oudenhove, L., Zhernakova, A., Vieira-Silva, S., and Raes, J. (2019). The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression. Nat Microbiol 4, 623-632.