Mindfulness

Mindfulness of Body While With the Instrument

Using the Satipatthana Sutta for the musician.

Posted March 1, 2021

Probably the most popular Buddhist teaching on mindfulness meditation is the Satipatthana Sutta. This text was compiled sometime during the first century B.C.E. and serves as a detailed practice and theory manual for mindfulness meditation. A sutta (Pali) or sutra (Sanskrit) is a manual. The word in English is thread and signifies a line of thought that ties ideas together in a meaningful and useful way. Satipatthana can be understood as presence of mindfulness. I like to think of satipatthana as being aware of being aware.

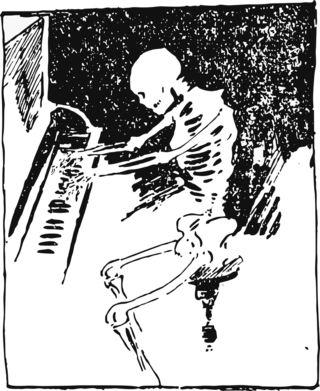

The first part of the manual introduces mindfulness of body studies. These first exercises explore all of the aspects of the physical body, beginning with the breath and concluding with the contemplation of the corpse after death. The mediations on the body are of particular interest to musicians. I will offer an adapted practice for the mindfulness of body while making music.

Bhikku Analayo, in his text, Satipatthana Meditation: A Practice Guide, suggests that we cultivate mindful awareness of our body by scanning the anatomy from toe to head. We systematically contemplate the skeletal structure, the flesh (internal organs and muscles), and finally the skin. We then focus our contemplation on the four elements of the body: earth (solid aspects of our body), water (liquid aspects of our body), fire (temperatures of our body), and wind (our animated bodies).

We can undertake this meditation before playing the instrument or while playing. One can play a familiar piece, play scales, a long-tone, or free-playing. The focus will be on the body while playing, not on what is being played.

Begin by sitting and focusing on the breath. In the breath, we become aware of the motion of the chest rising and falling. With each inhale and exhale, we become aware of the cool and warm air on our nostrils, throat, and lungs. We think of the ribs forming structure to our torso and the supple skin and sinews that hold the skeleton in form. With each inhale we are aware of the rising and falling of the anatomy.

We now focus our attention on the skeleton. Feeling our upper and lower teeth touching allows us a visceral awareness of the solid (earth) element of our anatomy. With this awareness of the hardness of our bones, we focus on the toes and contemplate the presence of the skeletal structure that supports us. Scanning through the feet, ankles, and legs, through the pelvis, chest, arms, hands, shoulders, and neck, we conclude at the skull. Each skeletal part has its moment in the spotlight while we are scanning. Parts of our structure that we might have never paid attention to are brought into awareness. This offers us an opportunity to contemplate posture while sitting or standing with our instrument.

Our attention will now turn to the flesh or internal parts of our body. We scan from the top of our head, down to our toes, remaining aware of the fleshy muscles that bring the element of the skeleton into motion (wind element). We become aware of how our body moves and in which muscles we are expressing the most motion. We can also become aware of using too much effort or tension in our playing. Asking the muscles to relax and economizing our effort and motion can result in a more pleasurable and meaningful musical experience.

Finally, we focus our attention on the skin. Scanning from the toes to the scalp, we are aware of the suppleness (water) of our skin and how the sensitivity of the skin’s nervous system allows us to feel the piano pedal beneath our toes, the keys or strings beneath our fingers, and the mouthpiece against our lips. A pianist might pay attention to the sensations of the hand while playing passages on the piano.

Using the first part of the Satipatthana Sutta to explore the three anatomies of the body and the four elements, can offer us an opportunity to learn from our bodies and to cultivate a more centered awareness while making music.