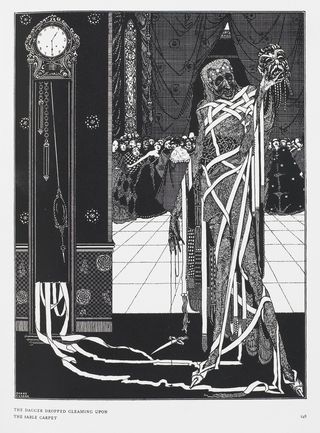

In Edgar Allan Poe's "The Masque of the Red Death" (1842), Prince Prospero lives a life of pleasure in his castle as a plague rages through the countryside. On a particularly festive evening, the prince hosts a masked ball. An unwanted guest enters: The mask which concealed the visage was made so nearly to resemble the countenance of a stiffened corpse that the closest scrutiny must have had difficulty in detecting the cheat.

The gathered gentry are seized with horror and disgust, and Prince Prospero chases the guest with a dagger: "Who dares? Who dares insult us with this blasphemous mockery? Seize him and unmask him."

He is repellent; how can they seize him? The guest is a defamation of the very way of being of the revelers. To capture him would be to hold your shadow in place as you turn a corner.

We are told no amount of attention to the visage will unmask it; it must not be a mask. Our guest cannot be unmasked; he is an assertion, a ghost sent from deep in the Earth. Beneath the mask is the void.

The masked figure is the end of the party, the illness-unto-death. It seems the vitality and confidence at Prospero's party are quite fragile indeed. It is interrupted every hour by the ebony clock when a tense silence reigns. Do the revelers know that their charade of leisure is built around a hollow core, that living in such a manner is a slight impossibility that can be taken away in one fell swoop?

Poe draws from a long tradition of scourge literature. The Black Plague killed 75 to 200 million people in Europe; it also brought to life Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron in which a gang of beautiful youth spends a bucolic weekend in a Tuscan pleasure villa. The stories, the danse macabre, are a relief from the death and destruction wrought by the devastating epidemic.

Like Scheherazade, who makes up stories during the dark times under King Shehryar. Or Far-li-mas in the Ruins of Kasch in which Roberto Calasso writes, storytelling teaches us how to live outside the cycle: It is the esoteric of the esoteric, the secret of the secret. In the inebriate suspension of the word, a way of life comes to light after the suffering and sacrifice, and yet the stories we tell ourselves retain the diluted gesture of sacrifice. The Renaissance was itself an exhalation, a rebirth of the human spirit after the tension of these epidemic waves of misery.

The halcyon days of industrial modernity (1870-1914) ground to an end in the trenches of the Somme, of Verdun. The post-war global order we live in is a relief from the killing fields of the World Wars, but it is also an economic bubble. Will the next stage of our civilization be a sudden or slow squeeze of extinction? Who will inherit the tawdry portion?

According to Carl Zimmer in A Planet of Viruses (2011):

"Viruses outnumber all other residents of the ocean by about 15 to one. If you put all the viruses of the oceans on a scale, they would equal the weight of 75 million blue whales. And if you lined up all the viruses in the ocean end to end, they would stretch out past the nearest 60 galaxies."

Our tale is being written: It draws from the cultural imagination of disaster exemplified by George Romero, who, in his "Living Dead" series of films, depicts the disintegration of public space wrought by the sudden shock that zombies wreak on our normal lives. Like the unwanted guest entering the party, the undead zombies break through the illusion of civilization, of our everyday joys and pains. But they cannot be seized or unmasked—they are us, and we are them. Who, then, makes the zombies?

The guests stumble drunkenly at the party as the disease spreads. Prospero announces that to protect his guests, they must each be quarantined. In their safe rooms, they are free to exercise freedom, to rest in pleasure. The quarantine is not much different than what the guests would normally do.

God is dead. Everything is available (for streaming). Scheherazade lulls us in an unending binge. But these boundless hours of leisure breed discontent with content. How long can the quarantine last? Will there be a slow strangling of the public sphere during the quarantine by paranoia and suspicion of the unwanted guest? The act of escape into pleasure, into seclusion, is itself contagious.

How did the revelers in Prince Prospero's castle react?

…summoning the wild courage of despair, a throng of the revelers at once threw themselves into the black apartment, and, seizing the mummer, whose tall figure stood erect and motionless within the shadow of the ebony clock, gasped in unutterable horror at finding the grave cerements and corpse-like mask, which they handled with so violent a rudeness, untenanted by any tangible form. And now was acknowledged the presence of the Red Death. He had come like a thief in the night.

The psychology of contagion depicted by Edgar Allan Poe remains pertinent as we face another wave of a viral pandemic that reminds us we are attending a party with very fragile boundaries. When an uninvited guest appears, pandemonium ensues. The disruption enables us to see ourselves for what we are, but it also spreads irrationality like a prairie fire.

We infect ourselves and each other with these visions of destruction. Like the infinite freedom of the remaining few during a zombie apocalypse, what serves as an escape is constantly imperiled by the reality outside the gates. We have so many stories about the end times of civilization that, when a real threat arrives, when an unwanted guest appears, we are all too easily driven mad with fear.

References

Calasso, R. The Ruins of Kasch. (1996). Cambridge, MA.: Belknap Press.

Edgar Allan Poe (1842). The Masque of the Red Death.

George Romero. Night of the Living Dead; Dawn of the Dead; Diary of the Dead.

Mark E Smith and The Fall (1982). Hex Enduction Hour. Kamera records.

Carl Zimmer. (2011). A Planet of Viruses. Chicago, IL.: University of Chicago Press.