Relationships

Self, Society, and Our Stuff

How do objects, things, and possessions shape our lives?

Posted June 12, 2013

“Things embody goals, make skills manifest, and shape the identities of their users…To understand what people are and what they might become, one must understand what goes on between people and things. What things are cherished, and why, should become part of our knowledge of human beings.” (Csikzentmihalyi and Halton, 1981)

An industry focused on stuff.

This morning The Atlantic ran an interesting article reporting that, rather than our stuff making us happy, it is actually the act of wanting and the idea of owning stuff that creates our joyful emotions. Though some reports disagree, a vast body of literature exists that debunks the idea that higher incomes and the resulting influx of stuff makes us happy.

In our increasingly consumer-driven culture it seems important to consider the significance of our material possessions. In their book, The Meaning of Things: Domestic Symbols and the Self (1981) Csikzentmihalyi and Halton write about the importance of understanding our relationship to the things that surround us. According to the authors, we use objects to express and relate to our self, others, and the larger world around us.

Through the use of objects we attempt to both differentiate and integrate ourselves; objects help distinguish us from others and also help us connect with larger society. Csikzentmihalyi and Halton write about the importance of striking a balance when interacting with our material world. According to the authors, both relying on objects too much to establish individuality and conversely, using objects to relate to one another too closely, leaving little room for individual development, can lead to problematic situations and relationships. It seems that finding a middle ground in which objects help us learn about and express our selves while also linking us to others and the cosmos is a foundational step in navigating our relationships to objects and things.

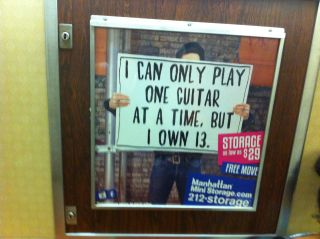

It is undeniable that objects and material possessions play vital role in our daily lives. As time moves forward, this is perhaps increasingly true. Australian author and public intellectual Clive Hamilton contends that over the past century, society has shifted from a production to a consumption sphere. Due to this shift, instead of focusing on the production of goods to meet needs, we now focus on the process of consuming goods and our consumption drives social change. This idea finds support in anti-consumption initiatives such as The Story of Stuff Project. Hamilton holds that the shift from production to consumption has changed the way we relate to things, relying on them heavily for the formation of our individuality and also using them as a major vehicle to connect with others.

Though this seems to match up well with Csikzentmihalyi and Halton’s writing on object relations, the question of balance becomes important. According to Hamilton, the act of defining ourselves by what we consume rather than what we create has hindered our ability to relate to one another. These changed relations between things and the self results in identities no longer based on life stories but rather based on the products we use and consume. In a consumption society, participation does not rely on material need but is founded on the assumption that consuming goods and owning possessions will make an individual a happy, well-established, connected member of society.

So it appears that according to both Hamilton and Csikzentmihalyi and Halton, when our relations with things become unbalanced, our sense of self, connection to others, and understanding of the larger world also becomes unbalanced and muddled. This question of balance has been addressed in various ways, including reassessing our connection to our stuff and thinking through necessities versus desires. According to various authors on the topic and individuals engaged in simple living, it appears that an integral part of the simple living lifestyle includes this process of thinking through the importance of stuff and our relationship to our possessions.

Richard Gregg was an early proponent of “voluntary simplicity” stating that it “involves both inner and outer condition. It means singleness of purpose, sincerity and honesty within, as well as avoidance of exterior clutter, of many possessions irrelevant to the chief purpose of life… It involves a deliberate organization of life for a purpose.” Along with the ideological components of simple living, it appears that it is pivotal to consider the role that possessions play in our lives. Furthermore, predating Hamilton, E.F. Schumacher, author of Small is Beautiful (1973), aptly pointed out the damaging effects of endless growth, increasing consumption, and the changing nature of ownership.

Less clutter, more time?

According to Duane Elgin, author of Voluntary Simplicity (1981), simple living is not about completely turning away from the material world but rather about shifting the focus away from the material and towards the experiential aspects of life, “living more ever more lightly and aesthetically.” As individuals focus less on stuff, they have more time for them selves and fulfilling experiences and relationships. In her book Choosing Simplicity (2000), Linda Breen Pierce writes about the experiences of individuals who choose to live simply. Before changing their lives, they often felt burdened by too many possessions and the tiring actions that were required to upkeep that lifestyle. By choosing a simpler lifestyle, these individuals report feelings of increased freedom due to the reduction of possessions and they prefer having fewer possessions for various reasons, often because it allows them to spend their time in new and different ways.

So while we obviously cannot live without objects, things, and stuff, it seems that striking a balance between necessities and our desire for and reliance on things, is important. Perhaps consciously navigating our material lives, knowing what we need versus what we desire, and making good use of the things we do have could help us better know ourselves, connect with others, and increase our understanding of our place in the world.