Fear

Cancer-phobia: Our Fear of Cancer Is Outdated and Harmful

Understanding that fear, and recognizing the harm it does, can protect us.

Posted November 13, 2023 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Despite great progress, we fear cancer more than any disease.

- Understanding where that fear comes from and what it does to us can help.

- Cancer is a natural disease that has been found in fossils more than one million years old.

This is the first in a series of posts based on my new book Curing Cancer-phobia: How Risk, Fear, and Worry Mislead Us.

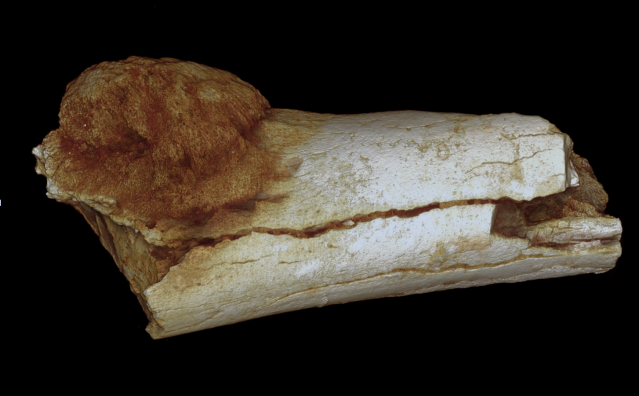

Cancer is a natural disease. Long before there were carcinogens like coal tar, cigarettes, and industrial chemicals, there was cancer. It's been found in fossils more than one million years old. The lump on that 1.7-million-year-old tibia is bone cancer.

And cancer has always been feared because, until recently, no cancer could ever be cured. But the deep and universal fear of cancer we know today is new, little more than 100 years old, because not until the turn of the 20th century did we start to live long enough for cancer to become common.

In 1900, the average American lifespan was 47 years, and cancer killed 64 people per 100,000. Only 5 percent of people said cancer was the cause of death they feared most, trailing tuberculosis, smallpox, lockjaw, consumption, leprosy—even being crushed in a rail accident, drowning, or being burned alive. But, by 1930, life expectancy was up to 61 years, and since cancer is largely a disease of aging—as mutations in our DNA that allow for uncontrolled cell growth accumulate—the cancer mortality rate had shot up to 160 people per 100,000.

Those were the decades when the modern fear of cancer we know today was born. Consider just a few historical events and trends that reflect the explosive growth of that fear back then:

- The American Society for the Control of Cancer, the forerunner of the American Cancer Society, got going in 1913.

- In the early 1900s, cancer-specific hospitals began to open, forerunners of some of today’s leading cancer-treatment programs—Memorial Sloan Kettering, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, the cancer program at Mass General Hospital.

- Alarmist media attention to cancer got going. The New York Times carried 131 stories about it in 1910, but 460 in 1930. Exploding media coverage of what one congressman called “more terrifying than any scourge that has ever threatened the existence of the human race” included a 1937 Fortune magazine and book titled Cancer: The Great Darkness.

- For the first time, people told their cancer stories publicly, so common today, starting with Congressman Robert Bremner in 1913, a friend of President Woodrow Wilson.

- Fear of environmental carcinogens also got going back then. In 1915, the New York Times published an essay titled “Civilization Has Created a Long List of New Diseases: Medical Science Forced to Grapple With Ills That the Flesh of Long Ago Knew Nothing Of.” Indeed our sweeping sense of “cancer” as synonymous with evil accelerated back then. Henry Miller named his 1934 book Tropic of Cancer not for the disease itself, but because “cancer symbolizes the death of civilization, the endpoint of the wrong path.”

- The idea of the fight against cancer as a “war” has its roots in the 1930s. In 1935, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, a women’s rights organization, teamed with the American Society for the Control of Cancer to create the Women’s Field Army, complete with uniforms, ribbons denoting military-like rank and ornamental swords, and organized in battalions, to wage a public education campaign about cancer. That helped pass the first National Cancer Act from Congress, creating the National Cancer Institute, in 1937.

- Public philanthropy for cancer first took off in 1948, when the Jimmy Fund was created using the popular radio program Truth or Consequences to introduce a national radio audience to “Jimmy,” a young boy in Boston being treated for leukemia. People across America wept as they heard Jimmy, from his hospital bed, describe his favorite Boston Braves players, and one by one they came into his room. Since then, the Jimmy Fund alone has raised more than a billion dollars.

- The atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons in the 1950s gave rise to the international “Ban the Bomb” movement, which, in turn, gave rise to the modern environmental movement, which was initially focused solely on the cancer risk from radioactive fallout from bomb tests. Rachel Carson’s 1962 Silent Spring, written as she suffered from breast cancer, likened modern chemicals to that fallout: “Chemicals are the sinister and little recognized partners of radiation in changing the very nature of the world.” “Against these carcinogens which his own activities had created man had no protection.” These are the roots of the belief that cancer is mostly caused by industrial products and processes, a dogma of modern environmentalism.

- Soldiers addicted to cigarettes they’d been given during World War II to help keep them awake led to an epidemic of lung cancer in the 1950s, and the controversy over whether cigarettes cause cancer, which gripped the country for two decades, began.

By the middle of the 19th century, all these trends had helped make cancer so feared that fear alone was imposing its own costs. In 1955, in a Life Magazine article entitled “A plea against blind fear of cancer,” Dr. George Crile Jr. (Rachel Carson’s oncologist) wrote, “it is possible that today, in terms of the total number of people affected, fear of cancer is causing more suffering than cancer itself.” He described this as “a new disease,” which Crile named “Cancerphobia”

Nearly 70 years ago, Dr. Crile wrote, “already doctors are seeing increasing numbers of healthy patients who suffer only because they are afraid of getting cancer. This fear leads both doctors and patients to do unreasonable, and therefore dangerous things.” Things have only gotten worse. We’re so afraid of cancer today that millions more screen for cancer than will be helped by that screening, leading to discovery of thousands of tiny early cancers that are “overdiagnosed”; the cells look cancerous under the microscope but the disease will never grow or spread or do any harm. That leads to tens of thousands of unnecessary surgeries, “fear-ectomies” to remove what is frightening but not threatening, that do enormous harm. The health care system spends nearly $15-billion dollars a year on this overscreening and overtreatment.

There are reasons why our sometimes excessive fear of cancer persists despite progress that has made roughly two-thirds of all cancers treatable as chronic diseases or curable outright. We have been repeatedly promised, with grand “Moonshot” metaphors, that our War on Cancer will produce a sweeping “cure for cancer”… that we will be entirely rid of this menace … but that promise is unfulfilled. And cancer has psychological characteristics that make it particularly frightening, which we will explore in the next part of this series.

Our modern fear of cancer is out of date, excessive in some ways, and profoundly harmful. Understanding the unique modern history of our fear of cancer, and the psychological/emotional factors that make it particularly fearsome, can help us reduce some of that harm.

References

AJ Willingham. Scientists find cancer in million-year-old fossil. CNN. July 29, 2016.