Anger

Personal Histories and Dynamic Systems

How can personal histories be incorporated in psychological science?

Posted October 25, 2019

Why don’t people in the other political party accept my slam dunk argument against their favorite public figure?

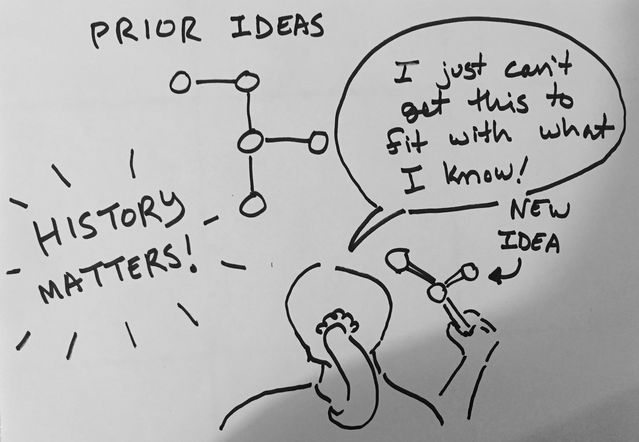

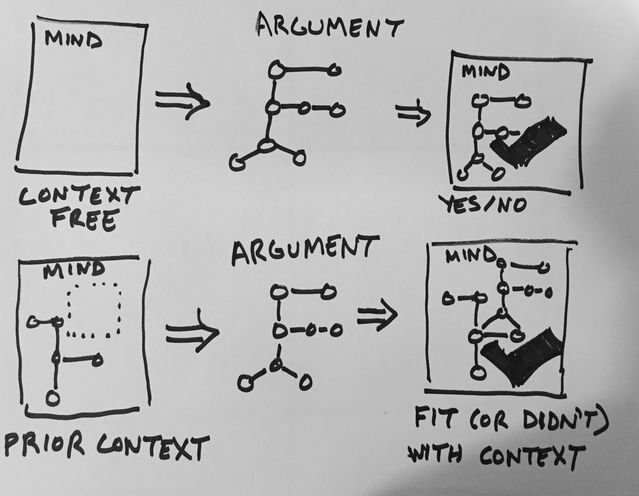

People on both sides of the political spectrum share articles and videos they believe “prove” or definitively demonstrate that people on the other side of an issue are wrong. Yet these kinds of arguments rarely seem persuasive to people in the opposing political party. Why is the same argument persuasive to some people but not to others? Don’t the facts just speak for themselves? From a dynamic systems perspective, not quite.

The framework that suggests any particular argument can be definitively adjudicated based only on the limited set of facts and logical statements in that argument strips away the statement’s context. The dynamic systems perspective is one way to put that context back in place.

A common feature of dynamic systems is hysteresis, or dependence on history. That means that the influence of a particular factor on a system depends on the previous history of that system. In other words, how convincing a political argument is doesn’t just depend on its content; it depends on from which side you’re coming when you hear it. The facts don’t change. The context of the system changes.

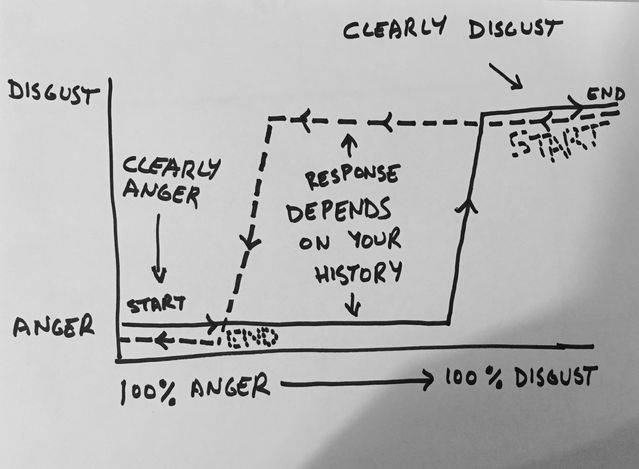

Simple models of hysteresis typically examine how a system responds to a single variable being gradually changed over time. This was demonstrated in a study that examined facial expressions of emotion being slowly morphed. The first image a participant would see was a very clear, strong expression of anger (for example), and the participant would be asked to indicate if the expression was anger or disgust. Then the same image would be blended with a little bit of a disgust expression, and the participant would have to say whether this new expression was anger or disgust. Over a series of 29 images, the anger expression was blended more and more with a disgust expression, until the last image was pure disgust. The researchers were interested in finding out at what point people thought anger turned into disgust.

Moving from anger to disgust was one condition in the experiment. Another condition started with a disgust expression and gradually blended in anger. A hysteresis effect would mean that the point of transition—switching to say an expression was anger or disgust—did not depend just on the information being presented. The “facts” of the face—what it looked like—were not enough to decide. For a hysteresis effect, the previous history of the system, meaning where the images started, would alter people’s judgments. This is exactly what the researchers found.

If you started by seeing an anger expression, you were more likely to keep saying the expression was angry until after the midpoint of the blending. You might not switch to saying the expression was disgust until only about 1/3rd of the expression was anger—and 2/3rd was disgust. But if you started by seeing a disgust expression, there would be a different transition point. You would keep saying that the expression was disgust until about 2/3rd was anger and only 1/3rd was disgust. (Note: these are not the exact numbers found, but rough approximations. Exact numbers differed across other experimental conditions. Also, not all pairs of emotions demonstrated this type of hysteresis effect.)

This effect is important when you start thinking about how the 50 / 50 split face would be interpreted. If you were to think in terms of a context-free model, where all that matters is the information being presented at that moment, you would just say it’s random whether you see it as anger or disgust. After all, participants in the study gave mixed responses: many labeled that ambiguous face anger, many labeled it disgust. But that would obscure an important regularity. Which label you gave wasn’t random, it depended on what kinds of faces you had seen previously. The previous state of the system mattered.

Think back to trying to people posting arguments on social media. How would history matter in this context? Imagine one person is starting with a progressive position on a given issue and pro-conservative arguments are slowly being introduced on their timeline. That person’s opinion might continue to fall on the progressive side long past the point of a 50 / 50 split in terms of arguments. Perhaps their opinion wouldn’t shift until 75% or 90% of the strong arguments fall on the conservative side. Of course, the reverse would then be true for a person starting with a conservative position on an issue who is slowly being introduced to progressive arguments.

Dynamic systems research allows earlier states of a system—a person’s or society’s history—to affect its current behavior. In fact, hysteresis is just a simple example of how dynamic systems can do this. The more complicated “Cusp Catastrophe” model, which has been applied to attitude change, is a dynamic model that adds information about when hysteresis does or doesn’t occur. And, of course, the psychology of why people hold political views involves many factors. A person’s history of beliefs is just one of these. Yet psychology is beginning to have enough sophistication as a field to start thinking more seriously about history and context. Dynamic systems theory provides a powerful set of tools for doing this.

References

Flay, B. R. (1978). Catastrophe theory in social psychology: Some applications to attitudes and social behavior. Behavioral Science, 23(4), 335-350.

Sacharin, V., Sander, D., & Scherer, K. R. (2012). The perception of changing emotion expressions. Cognition & emotion, 26(7), 1273-1300.

Van der Maas, H. L., Kolstein, R., & Van Der Pligt, J. (2003). Sudden transitions in attitudes. Sociological Methods & Research, 32(2), 125-152.