Bias

Should We Throw Out the GRE?

Graduate programs are dropping the GRE requirement. Will it reduce bias?

Posted September 21, 2019 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

I was out with my friend Heather, who was in mt Ph.D. program in quantitative psychology, when one of our non-psychologist friends asked her what she studied. She replied: “My research is about how to make psychological tests less biased. So when people take the SATs or other tests, the questions shouldn’t be easier for one group—like men versus women—to answer.”*

Her research area is called measurement invariance, and it involves continually coming up with ways to better ensure—using rigorous statistical criteria—that test questions are fair for everyone who takes tests. This actually came up on an episode of Malcolm Gladwell’s podcast this season. Gladwell went to talk to test makers, who described their day-to-day work to him, much of which involved removing biased questions that would have otherwise gone into standardized tests (in his interview, they were talking about the LSAT).

I thought about my friend Heather as I was reading recently about a movement in science and technology graduate programs to stop using the Graduate Record Examinations (GRE). There are strong arguments for dropping the GRE: it costs $205 to take, which can be prohibitively expensive for some students, and test prep and tutoring can raise scores on the GRE—further giving wealthy students an upper hand in admissions. The skills it assesses also may not be the primary determinants of success as a scholar: passion and perseverance likely matter as much—if not more—than your ability to solve math or word problems quickly.

But then there’s the fact that you can do an entire Ph.D. in figuring out better ways to de-bias standardized tests. In a recent impassioned twitter thread, a quantitative psychologist expresses her frustration with the arguments against the GRE. It was originally instituted as a method of recruiting candidates to Ivy League schools who weren’t already part of the “Old Boys” network of recommenders. Its continued research is what allows us to accurately assess bias in tests. It employs hundreds of researchers who are constantly trying to improve tests. (That is not to say that the GRE is effective at increasing diversity—historically it has been explicitly used by some universities to try to reduce diversity.)

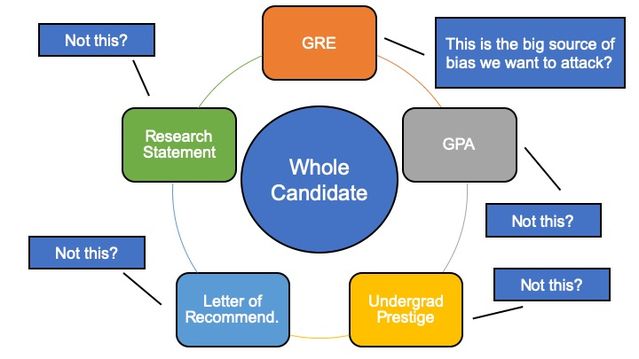

Assuming my university’s psychology program follows through on their promise to drop the GRE for graduate admissions, what would be used to make decisions? Undergraduate transcripts, research statements, and letters of recommendation. The question then becomes: are these really less biased than the GRE? We’ve got an army of researchers doing sophisticated statistical analyses trying to make standardized tests more fair. Are we doing even a fraction of that work to make sure what gets left in the application isn't more biased?

Transcripts will give graduate programs the names—and the prestige rankings—of students’ undergraduate institutions. Undergraduate admissions at the most prestigious schools are now so competitive that acceptance for highly qualified candidates can feel like a coin flip. Further, wealthy students are often tutored and coached on how to get admitted. University prestige is therefore likely to be at least as biasing a metric as GRE scores. Additionally, grades at these various institutions may be handed out using different rubrics. When I was in college, people would say that undergraduates at Harvard would easily get A’s just for showing up; other private schools like Swarthmore were known to have lower average grades. Comparing GPA’s across institutions where grading differs substantially is definitely biased.

Research statements are a great place to find out about passion and perseverance—but they are also highly coached. Undergraduate students who are in touch with graduate students get multiple examples of successful essays, and faculty advisors often give feedback as well. This is good and helpful behavior by mentors, but it’s also biased. Applicants who are not coming straight from an undergraduate institution, but might be in the working world and don’t have people to coach them through writing, might not realize what they are missing in insider knowledge.

There’s another, subtler form of bias here: where you went to school, and how much time you had to cultivate relationships with faculty (as opposed to, say, work to support yourself), can play into how much help you get in writing your letter. People from wealthier backgrounds who didn't have to support themselves financially gain a leg up by being able to do unpaid labor in research labs, where they have the opportunity to learn about the "hidden curriculum" in academia. This willingness to do unpaid labor also plays into the next component of an application: the letter of recommendation.

Letters of recommendation may be the biggest potential source of bias. The word of a famous faculty member—as opposed to a newer or less established figure—means more. But undergraduate students may not know who the famous faculty are, and ideally are more motivated by the desire to learn about a particular topic area than by the "name brand" of the research lab. We should be rewarding students for their passion about a research topic, not their ability to ingratiate themselves with famous faculty. Moreover, who has access to “star researchers” is also unevenly distributed. Prestigious, hard to get into schools have more famous scientists working for them. Having access to these letters is therefore again dependent on biases in the admissions systems for elite universities.

Further, there is research showing gender bias in how letters are written. A study of medical school letters found that women were more often described as teachers or students; men as researchers or professionals. Under-represented minorities are also more often described as "caring" in medical school recommendations, suggesting that there are ethnic/racial differences in the way recommenders describe candidates. Research on recommendation letters in a psychology department showed similar gender bias, with women being described as having more nurturant, community-oriented goals—as compared to men being described with assertive, control-oriented goals. This community-oriented language was associated with a lower likelihood of being hired for a faculty position.

There is a certain level of discomfort with putting a number on difficult to define concepts like “quality of a graduate application.” No number can ever fully capture what an individual brings to the table intellectually or creatively. But when we reject careful measurement, we are rejecting an important tool for quantifying and reducing bias. By taking stock of gender, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status across all aspects of an entire application, we can better understand where bias comes from: the GRE, letters of recommendation, personal statements, etc. It’s easy to say we’re taking steps forward by jettisoning standardized testing: people hate taking them, and they have real flaws. It’s harder to step back and invest serious resources into studying the parts of the problem that haven’t had an army of statisticians carefully analyzing them.

Before we throw out standardized testing, we need to make sure the energy we expend on continually reducing biases in the GRE doesn't just dissipate. We should also make sure that we are continually reducing the bias in the other important parts of graduate admissions. Otherwise, I worry that we are just taking away one more way that students can demonstrate the particular skills they bring to the table—and potentially increasing the overall bias in our decisions.

*This is a paraphrasing of what she said, based on what I remember. Mostly I just remember my non-psychologist friend saying “wow, that was a really clear description of what you do.”