Bias

Why Being a Hypocrite (Especially Online) Is Probably Normal

We practice few values equally across all situations.

Posted May 10, 2022 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- People possess both personal (self-interest) and relational (cooperative) values.

- Many values people possess are situationally activated—they don't guide one's behavior all the time.

- Because of the presence of self-serving bias, people tend to behave in ways that benefit the self, which can lead them to act inconsistently.

On Twitter, there’s a personality called @DefiantLs, whose primary focus is sharing screenshots of past and present tweets as a way of pointing out the hypocrisy of others. And there’s a reason DefiantLs has over 740,000 followers: we dislike hypocrites. Evidence suggests we dislike hypocrites more than those who readily admit to behaving in ways we disapprove of. We even dislike them more than we do liars.

But what if I told you that, in many situations, hypocritical behavior might not be what we make it out to be? Might there be a logical explanation (beyond the conclusion that hypocrites lack moral character) for what appears to be others’ hypocritical behavior? The answer is yes[1].

First Up: Moral Values

All people possess values, but people vary in the weight they implicitly assign to different values. And these values, whether we’re talking about those included in Haidt’s Moral Foundation Theory (MFT), Curry’s Morality-as-Cooperation (MAC) Theory, or some other perspective, influence human behavior.

However, Verplanken and Holland (2002) demonstrated that many values are situationally activated, and once activated, those values are used as a primary guide to decision making in that situation – but only if those values are more central to how we view ourselves. The more central the value, the more likely it would be activated in a situation consistent with it. Values that are less central to our self-concept are less likely to be consistently activated, especially when a conflict exists with a more central value.

For example, someone who possesses compassion as a highly central value is likely to behave compassionately toward others much more consistently than someone for whom compassion is a more peripheral value. If compassion is more peripheral, some situations may activate compassion, but others may activate other competing values (e.g., hedonism, security) instead.

The values that are activated in a given situation, then, are integral to the frame of reference that guides our decision making. Borrowing from Deci and Ryan’s self-determination theory (SDT), how we think and behave when pursuing achievement might differ from how we think and behave when we are pursuing affiliation or competence.

We might even be pursuing all three at the same time, but it’s likely one of those values will take precedence if a values conflict arises. When values conflicts occur, those values that are more strongly activated are likely to serve as a more central guide to decision making than less strongly activated values.

And here’s the rub. We tend to possess both personal values (more self-interest-based values, such as those mentioned by SDT) and relational values (such as in Curry’s MAC theory)[2]. We pursue our self-interests, but we tend to do so in a way that accommodates relational values (as cooperation is important for our self-interest).

Let’s Welcome Self-Serving Bias to the Story

We’re generally motivated by our personal values, and these form the cornerstone of our self-interests. Our self-interests, though, are generally pursued while adhering to relational values. Curry offered a list of seven relational value domains – family, group, reciprocity, heroism, deference, fairness, and property[3] – and these values are activated at different strengths in different situations.

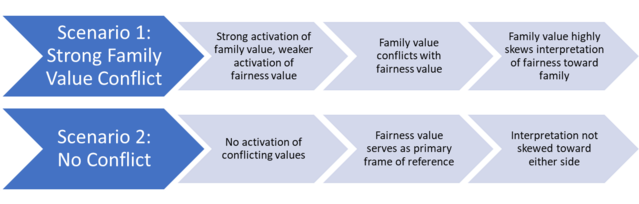

As with personal values, relational values can conflict. For example, we may value fairness, and, when activated, fairness can create a frame of reference through which we interpret a particular situation, such as the decision to punish someone for misbehavior. But our assessment of a comparable situation could differ if our fairness value now conflicts with another relational value, such as family. Hence, we might interpret a situation one way if we have no connection to the parties involved but interpret it differently if our fairness value is brought into conflict with the value placed on family (i.e., if someone involved is a close relation) or group (i.e., if someone involved is a member of a group we identify with). Such conflicts can alter how we judge a given situation.

When conflicts occur, we often resolve those conflicts in a way that is more protecting of our sense of self (also called self-serving bias). In the case of the example I just used, family is often more central to our sense of self than is fairness. As such, the activation of family can skew our interpretations of fairness in such a way that it biases our assessment of fairness toward one side (i.e., the side involving our family) of the fairness scale (see also Figure 1)[4].

The bias that occurs may range from weak to strong, depending on the discrepancy between the strength of the activated values. If there’s a small discrepancy between the strength of family and fairness, it may lead to only a slight bias toward family, but if the discrepancy is large, the bias toward family may be more extreme, and the outcome would have to much more strongly favor our family member for us to perceive the outcome as fair[5].

Motivated Reasoning: The Sidekick

Self-serving bias helps to explain why we might interpret seemingly similar events very differently and make what appear to be hypocritical behavioral choices[6]. When our personal self-interests are involved, we tend to be biased toward protecting those interests.

However, if it were merely as simple as having strong self-interests, more people would choose to engage in unethical (and illegal) behavior while criticizing others who engage in the exact same behavior (thus making us extreme moral hypocrites). After all, our personal values could be used to justify the choice to rob a bank, while simultaneously criticizing anyone else who engaged in the behavior (as it is a violation of the relational value of property).

But our behavioral choices aren’t just a function of self-serving bias. Our self-serving bias also must be accompanied by a way to justify our behavioral choices (also called motivated reasoning). For most egregious behaviors (especially of the illegal kind), the costs of pursuing our personal values at the expense of relational values simply do not justify the benefits, keeping us from reasoning our way into doing so.

Less egregious behaviors, though, may be much more likely to result in one set of standards for others than for ourselves. This is because the reasoning we use to justify our own actions in such situations is often different than the reasoning we use to criticize the behaviors of others in the same or comparable situation (as Hale & Pillow, 2015[7], argued).

We Are All Moral Hypocrites

In returning to the medium that initiated this post (Twitter), the social media environment is rife with situations that promote hypocrisy. There are generally few costs incurred for online hypocrisy, and the benefits of playing to one’s audience (garnering likes and shares) is often sufficient to justify the costs, especially when it is easy to reason our way into a justification for that hypocrisy (e.g., “here’s why my choice is excusable but theirs isn’t”).

Everyone has the potential to engage in moral hypocrisy. All it takes is the right situation with the right conflict in values and a strong enough justification to motivate hypocritical behavior. So, rather than using hypocrisy as evidence to conclude that someone is morally deficient, we might be better off understanding the motivational forces that led to the hypocrisy to begin with.

By deliberately giving thought to those motivational forces (with greater weight given to external motivators), we might better understand where others are coming from even if we cannot effectively put ourselves in their shoes. If nothing else, it might reveal the importance of their personal values to the arguments they make (and offer insight into our own), which could lead to more productive online conversations.

References

Footnotes

[1] If the answer were no, this would have been an awfully short post.

[2] See Verplanken et al. (2009) for how priming of the personal self and collective self can elicit different cognitive and behavioral strategies.

[3] The specific meaning of each isn’t important for our discussion, but Curry (2019) offers a full description of each one.

[4] I also discussed this same issue when explaining why it is unreasonable to expect politicians to “follow the science”.

[5] Anecdotally, we see this play out frequently in the criminal justice system, where family members of victims and defendants often have very different interpretations of the fairness of an outcome than do those who have no conflict of interest.

[6] The potential also exists to explain hypocritical behavior (especially when there’s a lengthy gap in between the events) as a function of maturity, a change of heart, or a change in perspective, but that often fails to accurately describe hypocritical behavior that occurs much more closely in time.

[7] Though they also argued that some types of hypocrisy can be more difficult to justify than others. Why that is, though, is unknown.