Guilt

Analysis of Death Row Inmates' Last Meals and Last Words

Rejecting a last meal: You are executing an innocent man!

Posted January 24, 2014

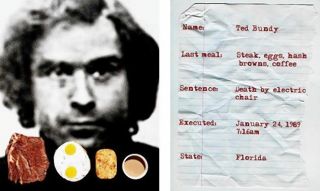

Ted Bundy's last meal

There are many benefits to having interesting friends on Facebook. In my case, given that fellow academics constitute a sizable portion of my online friends, I am at times privy to shared studies that I might otherwise miss (or perhaps only identify at some future date). The genesis of today’s post stems from such a shared study by my fellow Psychology Today blogger Hal Herzog. Thanks Hal!

The study in question was reported in a 2014 paper published in Laws and authored by Kevin M. Kniffin and Brian Wansink, both housed at one of my alma maters (go Cornell!). Wansink is a world-renowned food psychologist known for tackling fascinating and intriguing research questions perhaps none more so than the one reported herewith. Death row inmates face two key decisions prior to their imminent executions (see my earlier article on my position on the death penalty). First, they must decide whether to have a last meal, and if so they must request the items to be included in it. Second, they must provide any last words that they might wish to share prior to being put to death. In many instances, an inmate’s last words contain self-ascribed proclamations as to their guilt or innocence. Kniffin and Wansink examined whether an inmate’s self-ascribed guilt status was linked to their last meal requests. Specifically, they investigated: 1) the likelihood of declining a last meal as a function of self-ascribed guilt status; 2) the number of calories of the last meal as a function of self-ascribed guilt status; 3) the number of brand-name items within the last meal as a function of self-ascribed guilt status. The dataset was comprised of 247 individuals who were executed in the United States for the years 2002 to 2006. In effect, the researchers used different sources to content analyze inmates’ last meal behaviors as well as their last words (for additional details, please refer to the original study). Of note, the researchers point to the fact that several plausible effects might be operative, rendering it rather difficult to posit a priori hypotheses. Here are some of the key findings:

1) 10% of the inmates claimed to be innocent; 65% did not pronounce a position on their guilt status; and 25% admitted their guilt.

2) Those who proclaimed to be innocent were more likely to decline a last meal as compared to those who admitted their guilt (29% versus 8%; p < .01).

3) Those who admitted their guilt requested last meals containing 34% more calories than that those stemming from the two other categories of inmates (2,786 versus 2,085; p < .05).

4) Those who claimed to be innocent requested fewer brand-name items than other inmates for whom the researchers had the necessary detailed data (0.18 items versus 0.56 items; p < .05).

Bottom line: Death row inmates who head off to their execution proclaiming their innocence are more likely to refuse a last meal; they request a last meal containing fewer calories; and they ask for fewer brand-name items as part of their last meal.

Here is a list of some of my other food-related Psychology Today articles:

1. Food Prohibitions: God's Will or "Earthly" Cultural Adaptations?

2. Do Calorie Labels Curb Poor Food Choices?

3. Don't Go Grocery Shopping When Hungry!

4. The All-You-Can-Eat Chinese Buffet: Beware…Scientists Are Watching You!

5. Variety Might Be The Spice of Life But It Can Lead To Weight Gain

6. Huge Increase of Calories in Cookbook Recipes

7. You Want To Smell Better: Don’t Eat Red Meat!

8. Women's Preconception Diets and Their Likelihood To Have a Boy

Please consider following me on Twitter (@GadSaad).

Source for Image: