Genetics

Bare Branches With Rotten Fruit

The surprising and disturbing outcomes of surplus males

Posted March 19, 2018

“Why are you nerdy science types interested in such weird abstract stuff?”

Well…one reason is that we are weird abstract types of people…but another reason is that you never know when the solution to weird abstract problems is going to shine a light on something imminent, urgent, and as practical as a heart attack.

Take the issue of violence against women—I hope I do not have to argue that this is a serious problem, or one that needs urgent attention? Good. Then let us first take an abstract problem and see if it helps us understand it.

Fisher and the sex-ratio problem

Here’s the abstract problem: “Why are there (almost) exactly equal numbers of men and women in the population?” It turns out that the solution to the second problem sheds some interesting (and disturbing) light on the first. I’ll leave the practical implications to policymakers.

Despite the myriad ways there are of being male and female across species, and the wildly variant ways that species reproduce, it turns out that (with intriguing exceptions that I’ll leave aside for the moment) numbers of males and females are roughly equal across species. Why is this? The great biologist and mathematician Ronald Fisher solved the problem mathematically in the 1930s, and it has some implications that are little appreciated. (1) The essence of the solution is this: If being one sex is inherently more likely to pass on copies of genes then, by the law of supply and demand, the opposite sex becomes more valuable (genetically) to compensate.

Copies of genes? The first thing to take on board is that from the perspective of your genes you (me as well, let’s not take this personally) are just a strategy for getting copies of themselves into the next generation. Specifically—being male or being female are also just strategic options for those genes. Each sex supplies half of your ancestry, but it does not mean that the sexes do this in exactly the same way. For reasons discussed here (roughly—differential minimum parental investment) males constitute a slightly higher risk strategy—in genetic terms. (2) Humans can mess with the riskiness of this—and do so—but the genes bite back, and genes, unlike humans, are not concerned with morals or ethics when they do this. And they have time on their side—they are immortal while we are decidedly not.

Reproductive value versus reproductive variance

Every individual has a father and a mother, but that does not mean that every individual has the number of fathers and mothers in their ancestry. Indeed—we now know from genetics that each of us has about twice as many mothers as fathers in our ancestry. (3) This can be rather counter-intuitive so I will take a second to explain it. The total reproductive value of each sex must be equal—because if it is not then the value in genetic terms of being the less valued sex goes up. But individual reproductive value is not the same as total reproductive value. In the past, lots of men did not get to reproduce at all, while some did so very successfully. In other words, men show higher reproductive variance than women. Recently we have smoothed out a lot of this discrepancy by imposing monogamy (more or less) on the human population, but the underlying mechanisms are just lying dormant.

Here is one consequence that everyone can see: Because reproductive variance is the most important type of variance that there is, males are under selection to keep on trying different schemes to get their genes into the next generation. That’s what phenotypic variance is, and it tracks reproductive variance. In less technical terms that means that when it comes to measuring men we get, to use Helena Cronin’s lovely phrase, “more Nobels and more dumbells”. (4) Men occupy more (not all, just more) space at either end of any bell curve that has any implications for reproduction. Incidentally, this important (and largely unappreciated) fact gives a ready-made response to 99% of “battle of the sexes” questions.

For instance, when people have those utterly fatuous conversations about “Who is better at X, men or women?” the lack of appreciation of phenotypic variance versus individual reproductive value, makes many opinions pretty much worthless. Are men better at X than women? Which man? Which woman? Women want (at the ultimate level) the best contributors to their eggs possible, and one of the easiest ways of deciding this is to watch for the men to form some sort of local dominance hierarchy (men love doing this) of some phenotypic marker of genetic quality, and then pick the ones at the top of the heap. So, when you hear some blowhard in the pub saying things like “Men are smarter than women, name five things that a woman invented”, one reasonable response is to say “Name five things that you invented, smarty-pants”. Men (whatever you may have heard about the “Patriarchy”) do not share reproductive interests. On the contrary, if all the men on the planet dropped dead tomorrow, then Alicia Vikander might start returning my phone calls…

Moreover, we are all at some level perfectly well aware of this competitive element to reproduction. What does a woman say to a man she wants to reject utterly so that she crushes his present flirtatious behavior and any danger of his ever repeating it? “Not if you were the last man on earth.” Ouch. This translates to “Even in a hierarchy of one—you would still be a loser”. Being hit with that is like being that couple in an episode of The Twilight Zone who find themselves alone on a mysterious planet and (surprise surprise) the guy reveals his name to be “Adam” only for the gal to say, “That’s amazing my name is Ev…err, actually I think I have a headache.”

When sex ratios go awry

That is the lighter side of phenotypic variance and Fisherian ratios, what about the darker side? From the perspective of genes, males are a slightly riskier strategy than females. So—if there are more males there are to go around, the riskier (and nastier) the strategies favoured may become. The technical term for “more males to go around” is “higher operational sex ratios” (O.S.R.s). These are measured as deviations from 100 (parity) so that, for example, an O.S.R. of 104 would mean 104 males for every 100 females. There are a host of technical issues about how to assess these (they vary from birth for example, and the ratios during peak reproductive years are more important than at other times—but I am not going to have space to address these complexities here. See the references for follow-up).

The link between discrepant O.S.R.s is a powerful example of how what is good for genes may not be good for individuals or societies. And this is not confined to our species either. From fights that tend to kill offspring, through forced copulation, to group violence, high O.S.R.s result in what any reasonable modern moral individual would agree were bad outcomes.

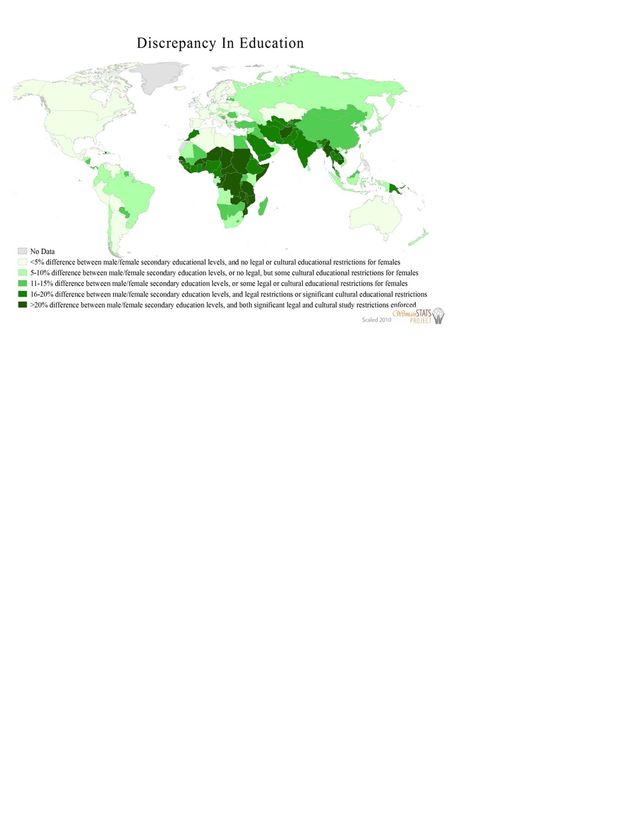

Back to humans: Across most of the planet high O.S.R.s correlate with male violence generally, and especially with violence against women. It also correlates with comparatively low investment in girls as evidenced by, for example, access to education (which is a cost). Surplus males are bad news at the local demographic level. The marginal ones are pushed to riskier and nastier strategies to the point where some authorities regard high O.S.R.s as a general security threat. In China they call these surplus males “bare branches” and it is a serious social policy question to decide what to do about them. Because—if we don’t, then we run the risk of the genes doing the deciding for us, and the results are not pretty. (5)

Demography isn't destiny

The realisation that humans obey the same rules as other species can badly mess with our sense of exceptionalism. “But humans have freewill”, someone might object. Treating hideous behaviours like rape, intimate partner violence, and gang warfare as, in part, demographically predictable, might be seen as lessening the responsibility of these behaviors. These are deep waters and I can do no more than ski across the surface of them here. It can be unsettling to realise that, at one level of magnification, individual humans might seem like de-individuated cogs in a vast machine. But I would like to suggest that this is a magnification issue—not a deep philosophical one.

Here is one way to see this in a similar demographic issue: Car crashes. Most people are probably unaware that the rate of car crashes is pretty constant in each country. Not only that, but there are some pretty well-understood power-laws relating speed of impact to severity of injury and likelihood of death. Unless steps are taken to lessen speed (say) the death rate will remain the same.

There are other factors too of course—enforcement of drink/drug laws, rigour of enforcing traffic violations, traffic volume and so on. Unless you change those one or more of those variables then the death rate on the roads will remain constant—at roughly ten a day in the UK, for example. No-one gets up in the morning planning to crash. No-one is deliberately careless or shuts their eyes. They all drive as carefully as they can. They are not the helpless pawns of forces beyond their control either—if they crash into someone because they are drunk or speeding then, quite rightly, the law will hold them criminally responsible. But it is possible to change the ecology in which they live so that certain decisions are simply less likely to happen. The implications of that can be somewhat unsettling—but maybe we need to be unsettled once in a while?

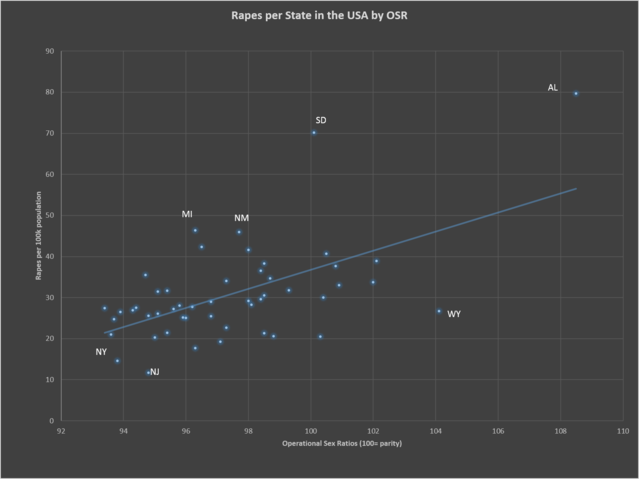

I did an informal test of one the predictions of O.S.R.s myself, correlating rape statistics across American states with operational sex ratios in those states. Given the fact that the O.S.R.s of American states are not that far apart I was frankly astonished that the degree of correlation was significant (p< .001) and of some effect (Spearman’s Rank coefficient .423). Obviously, it’s not the only thing going on, but it is one of the predictors. Like speed is a predictor of deaths on the roads. And, just like deaths on the roads, we can take the perspective of addressing individual driver responsibility (and there is nothing wrong with that). But we can also alter our scale of magnification and look at demographics. And when we look at demographics the data are clear—surplus men are a menace to women.

References

1) Fisher, R. A. (1958). Theory of Natural Selection. New York: Dover Publications.

There is higher male mortality during periods of parental investment, this makes males costlier in terms of rearing (though not per male born) than girls at the same stages. This results in selection favoring more boys at birth but also higher male mortality. Fisher rather brilliantly predicted exactly this happening. And it does. Total effort to produce sons = total effort to produce daughters, the sex ratio that we see is always biased towards the least costly sex. Fisher’s theory is really about investment, not numbers per se.

2) Trivers, R. (1972). Parental investment and sexual selection (Vol. 136, p. 179). Cambridge, MA: Biological Laboratories, Harvard University.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/hive-mind/201404/penis-mightier-th…

3) Wilder, J. A., Mobasher, Z., & Hammer, M. F. (2004). Genetic evidence for unequal effective population sizes of human females and males. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 21(11), 2047-2057

4) Cronin, H. (1993). The ant and the peacock: Altruism and sexual selection from Darwin to today. Cambridge University Press.

5) Hudson, V. M., & Den Boer, A. M. (2004). Bare branches: The security implications of Asia's surplus male population. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bose, S., Trent, K., & South, S. J. (2013). The effect of a male surplus on intimate partner violence in India. Economic and political weekly, 48(35).

Kokko, H., & Jennions, M. D. (2008). Parental investment, sexual selection and sex ratios. Journal of evolutionary biology, 21(4), 919-948.

One of the variables that has been left out in many studies is individual responses to social programmes—such as Chinas one child programme. It turns out that efforts to debunk the O.S.R. hypothesis of bare branches has ignored the normal human responses to authoritarian attempts to interfere with family life—ignore and circumvent the rules. In this case it turns out that the official OSR of China largely result from parents waiting longer to register daughters. So one reason for the lack of rioting and unrest across China is simply that the OSR were not a skewed as we might have thought. A recent paper (Stone, 2017) tested these hypotheses and found support for the evolutionary over the “culture of violence” explanations.

There have been some studies showing that lower numbers of men correlates with same-sex aggression. Alas, these studies failed to control for the fact that the “lower numbers of men” in question resulted from the fact that they were being killed off! It seems a bit rich to claim that low O.S.R.s are to blame for violence when it’s the violence causing the low O.S.R.s in the first place. It reminds me of the old plea for mercy on the art of someone who has murdered their parents on the grounds that you should take pity on them because they are an orphan.

The statistics for rape and O.S.R.s per states can be found here

http://edition.cnn.com/2014/02/03/opinion/sutter-alaska-rape-list/