Intelligence

So Your Gifted Child Gets All A's... So What?

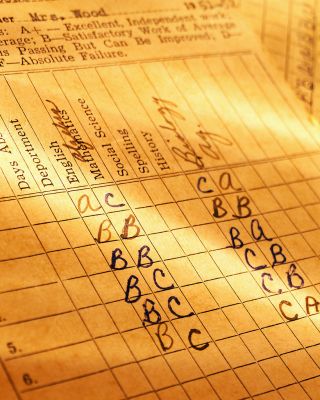

Grades are only a part of the school's information you should be considering.

Posted September 16, 2012

I was reminded a few days ago that already, in my school district, we are just a few days shy of the first marking period’s interim reports. Grades for each subject will be sent home so that parents can see how their child is faring thus far. Presumably, this gives the parents a heads-up about what the first quarter’s final grades will look like, should everything else remain the same. For some parents and students this is helpful information. That B in math could easily become an A if Johnny just turned in his homework more consistently. An average grade could be improved with some careful attention to the study guides the teacher provides before each test. Indeed, for those parents that are interested in their child’s progress at school, this first report can be a valuable tool as they try to set a tone for the year or troubleshoot academic issues early on, before it’s too late.

But for parents of gifted children—and even for the gifted students themselves—grades offered by the teacher can often be of very little help, especially when that gifted student typically gets A's.

To be clear, I will not be attempting to claim in this article that grades are unimportant or that grades have little value. Far from it. I consider grades to be an important piece of communication between parents and teachers about how a child is performing in class. For those students, gifted or not, who take full advantage of the learning opportunities offered at school, grades can be a terrific source of information and pride. Each of us reading this article right now can probably recall at least a class or two where the grade we earned felt exactly like that—earned. That B you struggled for in college made you work; you studied hard, you asked the right questions, you stayed up late in the library instead of going out with friends, and in the end, maybe you were even grateful for the B you received. (Of course, the converse is true as well: there were those classes, hopefully few, where the grade assigned to you seemed arbitrary at best; a paper that received an A one week, got a C the next with few comments provided to help you understand the rationale of the teacher’s grading system.)

The issue with grades and gifted students in particular, however, often revolves around a key element of the paragraph above, namely that grades can and should be an important piece of communication about how a child is performing in class. For gifted students particularly, I would argue, it is essential that grades be viewed merely a piece of the academic story, not its end. Here’s why: in many classrooms across the United States, gifted students are often able to pull A's on a standard report card with very little effort.

This statement is not likely to shock anyone, least of all the gifted student himself, but its implications are profound. When a child or parent regards the A on the report card as a sign of a “job well done” it is often tempting to rest at this level. Having little incentive to do anything differently, they neither seek further challenge nor change any of the (sometimes non-existent) study habits that led to this grade. Sara, for example, mastered the times tables when she was starting second grade. When her classmates were introduced to this in third grade, she had a leg up on them. Every test for her was easy, she had no trouble with the homework, and the teacher even used her skills to help other students in the room who required extra help.

So when Sara got an A for the first quarter report in math… so what? Sure, it shows that she has an understanding that places her at the top of her math class peers. But what did that A mean for Sara? In reality it means very little.

Most of us would like to believe that grades reflect serious effort and hard work on the part of the student to master the material. The grade of a B (over a C or D, for example) has meaning because it presumably reflects a higher level of achievement on tasks that demanded effort. But for gifted students like Sara who expended very little effort, this particular interpretation of “what a grade means” is irrelevant. To be sure, mom, dad, and Sara are quite happy: Mom and dad praise Sara for the A; Sara feels satisfied because, really, she didn’t have to work very hard; the feedback she receives is that all is well in school. Steady as she goes.

However, nothing but trouble comes when this typical notion of grades is accepted as the final arbiter of the child’s work ethic at school. There will be a time when Sara, used to getting A's, finally gets to that class where the A is not so easy to achieve. The work demands attention in a different way, and study skills that have not had a chance (or even a reason!) to develop in the past are suddenly, dramatically, and quite obviously lacking. Sara struggles then simultaneously to both master the material and discover the best way to manage her time. Along the way, she gets a few low grades, maybe even an F or two on a few key tests, and her self confidence plummets. Where math was once a source of joy, it is now a source of confusion and intense anxiety. Perhaps Sara will come across this class in high school where she will learn from it and rebound. Often, however, she won’t encounter it until college. And what a shame that is.

For gifted students, receiving high marks is very often not a true representation of the child’s work habits, potential, or even her depth of understanding of the material—and this is why you as a parent must seek more information. You must ask the teacher questions that will help you determine what that A means. These might include the following:

- What was the numerical average of the grade? (A 91% “A” provides somewhat more interesting information than a 100% “A.”)

- What, exactly, is the source of the grade? Homework? Tests? In-class projects? A combination of all three?

- What is the ratio of these elements to the final grade? How did your child do in each of those categories? (Is it possible, for example, that your child earned a high grade even though he turned in his homework only half of the time?)

- How can the teacher further stretch and challenge your child? If it is clear that Sara knew her multiplication facts early on, for example, what other kinds of homework might the teacher have assigned in its place? Instead of sitting through instruction and material she already mastered, could Sara have been pretested and then offered new material to study using a learning contract?

In an ideal world, appropriate levels of challenge would be offered to all students as soon as they begin school and would continue throughout a child’s career. But that is often, quite simply, not the case. It’s no one particular individual’s fault—teacher, parent, or child—but the stakes for not wondering and investigating what all those A's really mean are quite high.

Potentially too high to be ignored.

Question: Are you one of those people who, as a student, breezed through school only to be slammed by the reality of what it really meant to “work” later on? Tell us about in the comments section. I’d love to hear from you.