Motivation

How to Build Authentic Motivation

A laziness cure.

Posted June 29, 2023 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- There are many potential sources of why we do the things we do, including why we sometimes don't do them.

- Feeling "lazy” tells you that you have to start from somewhere else than where you are.

- Improving any area of your life will likely involve some experimentation because you are an individual.

There is no such thing as laziness. We often use the word “lazy” as a broad umbrella term to describe someone who is unwilling to perform certain tasks or duties. What we then fail to acknowledge, however, are the actual reasons why someone is unwilling in the first place. We ignore the many facets and causes of behavior, and simply reduce a person to the label of “lazy," as if laziness was an inherent part of their identity. To make matters worse, we've learned to attach shame and guilt to laziness, making us think less of the person we call “lazy” – whether other people or, more likely, ourselves.

Labels attached to self or others are dehumanizing when we fail to appreciate why. To avoid such objectification we need to know the actual controlling variables. Suppose, for instance, you learned that a so-called “lazy” adult was abused as a child whenever she showed initiative. Are you still comfortable freely putting that label on her? I hope not. And if not, when did you suddenly deserve less consideration than you would give to others? Why not bring an attitude of curiosity to your own so-called “laziness"?

If we were to dig deeper, we might learn that our unwillingness to perform certain tasks or duties might be fueled by…

- buying into a deep-seated fear of uncertainty.

- entanglement with a recurring worry over the future.

- adopting a sense of “not being good enough.”

- experiencing a lack of values clarity.

- a self-objectifying and overly demanding schedule, always filled to the brim.

- a poor quality of sleep at night.

- a lack of close and supportive relationships.

- a diet high in sugar and saturated fats.

…and many other such factors.

There are many potential sources of why we do the things we do, including why we sometimes lack motivation. What is responsible for your “laziness?” That’s hard to tell, because it always depends on you, your history, and your situation. There is simply no one-size-fits-all way to understand motivation. You are an individual and to move ahead you will need to be more curious about why.

Step 1: Look at What Drives Your Motivation

Unfortunately, the answers your mind gives you about your own behavior are often false or useless. For this reason, the first step in overcoming “laziness” (i.e., unwillingness) is to observe yourself more clearly. You need to notice how your engagement ebbs and flows and the situations that impact it. This may sound simple enough, and yet it’s far from it, because our minds are surprisingly bad at knowing why we do the things we do. Research has shown that the vast majority of our choices are driven by influences that go beyond the simple rule-based formulae we carry in our heads. For instance, holding a warm cup of coffee may influence you to perceive others as more warm and friendly. Yes, really.

This is one reason why seeking help from a professional can be helpful. They can point to our blindspots, especially if they have empirical help in understanding the processes that explain your behavior. Fortunately, you do not need to be aware of every factor that is driving your behavior – only of the ones that matter most – and you yourself can collect much of the information you need.

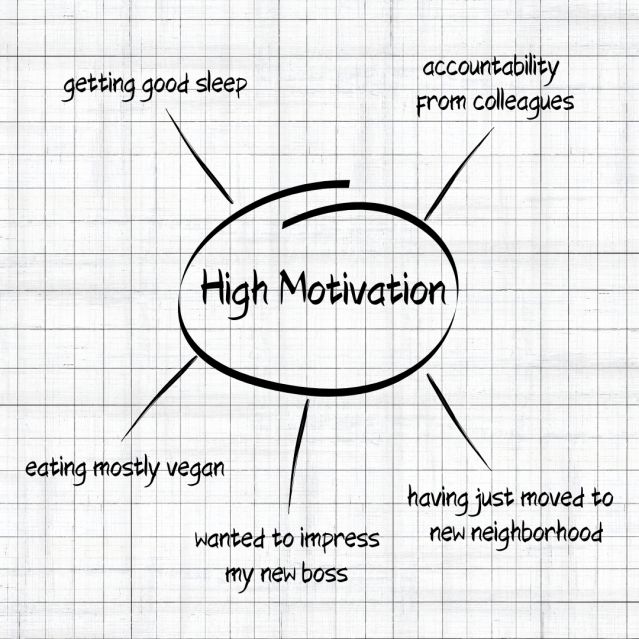

Start this refinement with a bit of introspection. First, rate your own level of motivation on a scale from one to ten (1 = having no motivation at all; 10 = being the most motivated you can be). Next, take a moment to think of a time when you felt more motivated than that (don’t worry – if this exercise is needed you won’t be at a 10 to begin with!). Now ask yourself, what was different back then? Write down whatever comes to mind that may have played a role. If in doubt, write it out. This is not about accuracy, but about capturing ideas. Your brainstorming might look like this:

Step 2: Do Something Different for a Week and Track What Happens

Not everything you have written down will be relevant, so the next step is to get more meticulous. Choose one factor that you think might be likely to influence your motivation; ideally, one you have some level of control over, like getting good sleep. Then, write down ideas about what you could do to change this one factor for the better. For instance, if you struggle with a good quality of sleep, you could get to bed earlier, buy a sleeping mask, stop eating late at night, defuse from worrying thoughts, etc. This is yet another occasion where a therapist can be invaluable, because they can point you toward effective strategies, and how to properly apply them.

Now pick one of the strategies you have written down, and actually make a change. If you think you need to go to bed earlier, do that and stick with it for a few days. Or buy that sleeping mask, and try it out. Do it consistently for at least a week. If you find this too difficult, make it simpler. For instance, if going to bed at 10 pm is too ambitious, try going to bed an hour later, or two. Meanwhile, continuously track what happens (there are a lot of apps that can help you) and rate how motivated you are on a daily basis.

Step 3: Step Back, Reflect, and Try Again

After you have implemented the change for a week, it’s time to reflect: Did your change have the intended effect? Did skipping late-night snacks actually lead you to fall asleep easier and feel more refreshed in the morning? If you were successful in improving your chosen factor, great! How did it impact your own motivation? If nothing happened, that’s less great but still good because you learned something.

The truth is that improving any area of your life will likely involve trial-and-error experimentation because you are an individual. What works for you may be nothing like what works for someone else. Some strategies may be helpful, and others not so much. And it’s hard to tell which is which until after you have given them a try. Furthermore, things that have helped you before can become ineffective—or the other way around. That means that learning how to move ahead is not a matter of “one and done,” but a continuous process. What may have been true years ago may not be true anymore.

You need to a) become aware of the shifting demands of your current life situation, and b) adapt to them accordingly. This requires practice and patience. It means a continuous process of learning to become more self-aware, noticing how your choices—both small and big—affect your life on a day-to-day basis.

The tricky part of “lazy” is that it tells you that you have to start from somewhere else than where you are. That’s impossible. Being genuinely curious about yourself will help you be more compassionate with where you are. If you are struggling with being engaged, it is because real factors are affecting you in very real ways. There is no such thing as “being lazy.” Find out how engagement works for you; it always goes a layer deeper.

References

Williams LE, Bargh JA. Experiencing physical warmth promotes interpersonal warmth. Science. 2008 Oct 24;322(5901):606-7. doi: 10.1126/science.1162548. PMID: 18948544; PMCID: PMC2737341.