Loneliness

What Emotion Does That Pokémon Represent?

How to use Pokémon with the Human Systems Emotion Wheel System.

Posted March 24, 2021 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Guest post by Brian Scott Hamilton

Emotions are complex. Even the most basic emotions can be difficult for adults to understand, let alone articulate. Now imagine that you’re four years old and trying to convey how you feel about someone taking your favorite toy. Are you angry or sad? Are you surprised or fearful? Maybe you’re appalled. Maybe you’re disappointed. Maybe you’re feeling all of these things, but you just don’t have the words to convey it.

When we look at the brain, it’s easy to understand why these problems exist. The parts of the brain responsible for generating emotions are known collectively as the limbic system (Shelat, 2020). This system represents some of the oldest structures in the human brain (Bruce and Neary, 1995). By contrast, the frontal lobe, the part of the brain that generates speech and controls emotional expression (Healthline, 2020) is one of the latest structures of the brain (Robson, 2011). It doesn’t even fully develop in humans until we’re 25 (Sapolsky, 2018).

This is one of the reasons that children and adolescents often have such a difficult time describing their emotions and explaining their behaviors. The parts of the brain responsible for processing these experiences are still developing (Sapolsky, 2018). It’s also why what we know consciously to be appropriate behavior and emotional expression is often different from how we actually behave and express our emotions.

The recognition of this duality is nothing new. Ancient humans recognized it and turned to the language and archetypes of mythology to help explain it (Glaveanu, 2005). Theseus fighting the minotaur, for example, can be viewed a metaphor for the conflict between our rational and emotional parts of the brain (Glaveanu, 2005).

While children today may not be familiar with stories like Theseus and the Minotaur, they are likely aware of more modern archetypes that convey similar themes. For example, in the Pokemon universe, the human characters explore the world, searching for various monsters that they can catch using special, handheld devices called pokeballs. Like the story of Theseus defeating the Minotaur, the human characters rely on cunning, strategy, and friendship to defeat the monsters they encounter. As they adventure, the Pokemon grow more experienced and occasionally even evolve into stronger Pokemon.

In many ways, Pokemon evolution mirrors the evolution of our own emotional understanding. When we are young, our ability to articulate our emotions is limited to words like happy, sad, angry, scared, bad, and gross. As we get older, our understanding becomes more nuanced: We’re not just sad, we feel despair or guilt. The more in touch we are with our emotions, the easier it is to describe these nuances and our understanding of them evolves.

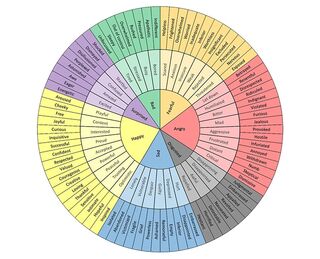

Not everyone is able to articulate their emotions or explain how emotions drive their behavior. To help clients develop these skills, Robert Plutchik developed the Emotion Wheel or Wheel of Emotions (Plutchik, 2014). The center describes basic emotions, with the outer spokes describing related, more nuanced emotions.

Since then, other versions of the emotion wheel have emerged. The Human Systems Emotion Wheel System, for example, divides emotions into seven basic types, which are then further subdivided as one moves out from the center (Human Systems, 2021).

Looking at the various Pokemon in the Pokemon universe, it is easy to see how different characters can act as archetypal representations of these various emotions. For example, Cleffa, with its rosy cheeks and bright smile, clearly expresses feelings of happiness. Koffing, a noxious floating ball that exudes noxious gas and feeds on the fumes from rotting trash, is clearly designed to evoke disgust.

The evolution of various Pokemon can also be useful to convey a developing and more nuanced understanding of emotions. Someone who is skilled at describing emotions might recognize that one is not just surprised, but confused or excited. As these skills develop, one might be able to convey perplexity or disillusionment.

When working with clients who are familiar with the Pokemon universe, it can help to demonstrate how different Pokemon represent different emotional states. The charts below are just one example of how clinicians can use these characters to help clients describe how they’re feeling.

A lot of the characters from Pokemon display their emotions through their appearance and expressions. Others convey it through their backstory. For example, Cubone, who in this chart represents sadness, does not appear particularly sad. However, if you know that Cubone mourns for its mother and wears her skull on its head to remember her, it’s more apparent how this creature can represent feelings of sadness, despair, loneliness, abandonment, and grief.

Clients who are particularly familiar with the Pokemon universe may quibble over whether a particular Pokemon truly represents the emotions assigned in these charts. For example, Grimer could just as easily represent disgust as it could bad feelings and this is a great place to start. Debating over whether a character accurately represents a feeling demonstrates that clients are actively engaged in thinking about these emotional concepts and trying to come up with archetypes that better represent their cognitive worldview. You might even encourage them to create their own Pokemon map for their feelings so that they spend more time thinking about these emotional concepts.

Learn more about Geek Therapeutics’ Geek Therapy Training and see our book, Integrating Geek Culture Into Therapeutic Practice: The Clinician's Guide To Geek Therapy.

References

Bruce, L.L, Neary, T.J. (1995). The Limbic System of Tetrapods: A Comparative Analysis of Cortical and Amygdalar Populations. Brain Behavior Evolution, Vol. 46, No. 4-5, p. 224-234. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1159/000113276

Glaveanu, V.P. (2005). From Mythology to Psychology – An Essay on the Archaic Psychology in Greek Myths. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, Vol. 1., No. 1. Retrieved from https://ejop.psychopen.eu/index.php/ejop/article/view/351/html

Healthline (2020). Frontal Lobe. Retrieved from https://www.healthline.com/human-body-maps/frontal-lobe#1

Human Systems (2021). Emotional Intelligence: A Different Approach. Retrieved from https://humansystems.co/emotionwheels/

Plutchik, R. (2014). Approaches to Emotion. Psychology Press, London, United Kingdom.

Pokemon (2021). Parent’s Guide to Pokemon. Retrieved from https://www.pokemon.com/us/parents-guide/

Pokemon (2021a). Pokedex. Retrieved from https://www.pokemon.com/us/pokedex/

Robson, David (2011). A Brief History of the Brain. New Scientist. Retrieved from https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg21128311-800-a-brief-history-of-…

Sapolsky, R. (2018). The Teenage Brain: Why Some Years Are (a Lot) Crazier than Others. Big Think. Retrieved from https://bigthink.com/videos/what-age-is-brain-fully-developed

Shelat, A.M. (2020). The Limbic System. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/imagepages/19244.htm