Fear

The Psychodynamic Brain

Emotion systems in the brain can run into conflict.

Posted September 25, 2017 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Freud once wrote: "I have no inclination to keep the domain of the psychological floating as it were in the air, without any organic foundation. Let the biologists go as far as they can and let us go as far as we can. Some day the two will meet."

In the field of neuroscience, that day may be approaching. There has been an explosion of interest in unconscious processes in the brain. Freud’s canonical idea that our emotional life has unconscious origins is now widely accepted. Neuropsychoanalysis — a movement that seeks to relate unconscious phenomena discovered through psychoanalysis to brain processes — is gaining momentum.

For example, neuroimaging studies and neuroanatomical studies of mammals have shown that there are two brain systems involved in fear. A system centered on a subcortical structure, the amygdala, is optimized for immediate response to possible signs of danger in the environment. A second brain system composed of various regions in the cerebral cortex is optimized for accurate perception of the environment, and thus the control of fear.

A dark patch in the ocean is instantaneously identified by the amygdala as a threat, which initiates a fear response, and we feel a surge of adrenaline. A moment later, the second, cortical system accurately identifies the patch as seaweed, and controls the fear response induced by the amygdala, turning it off.

From a psychoanalytic point of view, the existence of dual fear systems raises interesting questions about what happens when the behaviors that they support conflict. The relevant phenomenon is counter-phobia. Most people automatically experience fear just before they perform in front of an audience (thanks to the first, subcortical brain system). Nonetheless, we fight such fear and do what we need to do (thanks to the second, cortical system).

Indeed, Freud believed that “Inside of every phobic, there is a counter-phobic” — an unconscious desire to confront and master what one fears, rather than avoid it. That is, we are in conflict about what we fear. Consciously, we want to avoid it. Unconsciously, we want to approach and master what we fear.

Correspondingly, can the brain's dual fear systems conflict with each other — the subcortical system activating fear, while the cortical system simultaneously inhibits it?

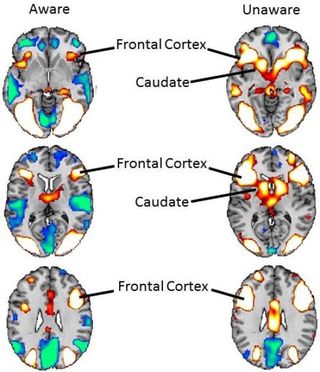

Bradley Peterson and I recently published a neuroimaging study that demonstrated such conflicting brain responses in spider-phobic people. When they viewed subliminal pictures of spiders (i.e., they could not recognize them), both brain systems were powerfully activated: the subcortical system that activates fear, and the cortical control system that inhibits fear and its associated behavioral responses — especially the frontal cortex and caudate nucleus, as shown in this figure.

When the same spider pictures were presented at a considerably slower speed — so that the phobic people could clearly see and thus were aware of the spiders, the cortical control system was hardly activated at all. Consistently, the phobics reported that they were experiencing considerable fear. Ironically, the control of fear responses occurred only when phobic people were not aware of the spider pictures. These findings are uniquely explained by Freud’s theory that unconsciously, we are conflicted about what we fear.

For decades, Howard Shevrin, Michael Snodgrass and colleagues have similarly manipulated awareness of phobic stimuli to study unconscious conflict in the brain. Their most recent study supported the canonical psychoanalytic hypothesis that unconscious conflict underlies anxiety. After interviewing patients with anxiety disorders, trained psychoanalysts selected words from the interviews that were associated with the patients’ unconscious conflicts. The researchers then presented these words to the patients either subliminally or within their conscious awareness. While these words were being presented, they measured brain waves that typically indicate the suppression of anxiety.

These waves spiked — indicating that the brain was suppressing anxiety — only when the conflict words were presented subliminally. No such pattern was shown when the patients viewed the same, visible conflict-associated words within conscious awareness. This pattern of findings suggests that patients’ unconscious conflicts were activated by the subliminal words, which resulted in the suppression of anxiety.

Freud is smiling from his grave. Modern science supports what he proposed: Human behavior is dynamic in nature, controlled by brain systems that can be at cross-purposes.