Psychiatry

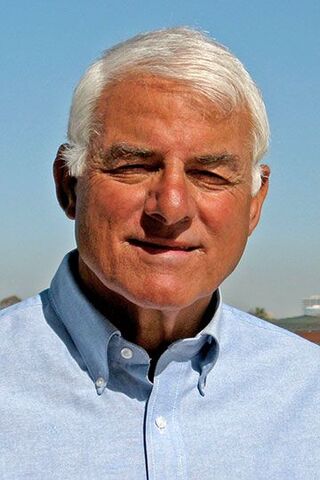

Allen Frances: Portrait of the Psychiatrist as a Young Man

An interview with the renowned psychiatrist and DSM-IV chair.

Posted April 12, 2021 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Allen J. Frances, M.D., is Professor and Chairman Emeritus of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Duke University School of Medicine. He served as Chair of the American Psychiatric Association's DSM-IV Task Force and has broad research and clinical experience in mood disorders, anxiety disorders, personality disorders, and schizophrenia. In recent years, he has become well-known for his concerns about overdiagnosis and medicalization in psychiatry, topics covered in his 2013 books Saving Normal and Essentials of Psychiatric Diagnosis. In 2017, he published Twilight of American Sanity: A Psychiatrist Analyzes the Age of Trump.

Mark Ruffalo (MR): I was first exposed to your ideas upon reading your Psychology Today blogs and then Saving Normal in 2013. What stood out to me was your pragmatism on the question of the nature or essence of mental illness and your defense of a comprehensive biopsychosocial model in psychiatry. As I've mentioned before, you (along with Dr. Ronald Pies) saved me from the Szaszian abyss.

I'd like to focus in this interview on your early life and career path in psychiatry since it may help place your current ideas in a broader context. Would you mind telling us a little bit about your early life growing up in New York, your family, early aspirations, background, etc.?

Allen Frances (AF): My choice of psychiatry as a career was part practical, part passion. My father's work in a pharmacy during the Depression convinced him that doctors weren't very smart but that they had very secure jobs. When I told him I wanted to be an English professor, he countered that I wasn't smart enough and that college teaching was a very insecure profession. I had to agree on both counts.

But there was also intellectual passion. I had started reading Freud, the philosophers, and Dostoevsky in high school and was hooked on joining a profession that could combine the humanities, the sciences, and helping people. My brother became a psychiatrist for the same reasons.

MR: The 1960s seem to have been an era of great promise and excitement in American psychiatry. When you started medical school in 1963, did you know you wanted to become a psychiatrist, or was this a decision you came to at some point as a medical student? What motivated you in this regard?

AF: It was crystal clear that psychiatry was my only possible choice among medical specialties because I was such a terrible clutz at physical things and much more interested in people and the meaning of life.

MR: After graduating residency in 1971, you decided to pursue psychoanalytic training, as did many psychiatrists of your generation. Some of your early work was on personality disorder. However, it appears that at some point, you became disenchanted with psychoanalysis. Can you tell us how and why this occurred?

AF: I am both an insider and outsider when it comes to psychoanalysis. I taught the Freud course at the Columbia Psychoanalytic Center for 10 years, starting in the late 1970s. And my favorite work activity throughout my career was doing and teaching psychodynamic psychotherapy.

My view is that Freud was overvalued in his own day and is now undervalued in ours. Overvalued then, because many of his best insights were really Darwin's and because many of his seemingly plausible speculations were necessarily based on the outmoded neuroscience of his times and have since been proved wrong. Undervalued now because his emphasis on inborn drives, the power of the unconscious, and the ubiquity of the repetition compulsion have been compellingly confirmed by current neuro and cognitive science.

Psychoanalysis was too important to be left to the psychoanalysts—they were too loyal to even his outdated theories and stuck doggedly to the couch and an insistence on sessions four times a week. Their biggest mistake was rejecting brief dynamic therapy and Aaron Beck's CBT as useful extensions of psychoanalysis into the practical world. I think the basic psychodynamic skills should be integrated into the toolkit of every psychotherapist.

MR: Having trained in New York City during what some consider the "Golden Age" of psychiatry, you had the opportunity to learn from some of the pioneers of modern psychiatric medicine. You've mentioned that Silvano Arieti, whose work I have an interest in, was an early mentor. You've also written very warmly about Robert Spitzer, with whom you worked on the DSM-III. Reflecting on your career, who do you consider to have been your greatest professional inspiration?

AF: I was very lucky in my teachers. I learned ECT from Lothar Kalinowsky (who was the first to bring it to the U.S.) and Max Fink (its main proponent for the past 50 years). Ron Fieve taught me about lithium shortly after he first introduced it to the U.S. I learned family therapy from Nathan Ackerman, group therapy from Milton Berger, and community psychiatry from John Talbott.

Sherv Frazier taught me the importance of the therapeutic relationship and of constantly monitoring countertransference. Harold Searles showed me how much I had in common with my most psychotic patients. Hilde Bruch taught me about eating disorders. Aaron Beck taught me CBT through his books.

Marsha Linehan taught me DBT as we collaborated on her books. I learned the fine points of psychotherapy research methodology from Marvin Goldfried when we worked together rating NIMH grants. Aaron Lazare taught me how important it is to include the patient as a partner in decision-making. Leston Havens infected me with the pure joy of being a psychiatrist. But my best teachers were always my patients and my second best were my students.

MR: As you look back on your career that has now spanned seven decades, what do you hope will be your most enduring contribution to psychiatry?

AF: Aside from my impact on patients, students, and colleagues, I don't think I have accomplished much in my career. Severely ill patients are even worse off now than they were 55 years ago when I began working in psychiatry. Then, about 600,000 were in hospital snake pits; now, they languish in prison dungeons or live homeless on the streets.

I have fought against overdiagnosis and overtreatment for 40 years—with little apparent success in containing either. I have fought for an integrated bio/psycho/social/spiritual model—but parochial reductionism abounds. My career has been a wonderful ride, but I never reached any of my desired destinations.

MR: Thank you very much for taking the time to participate in this interview. I'd also like to thank you publicly for your support and guidance early in my career. I'm certain that your work will continue to inspire young psychiatrists and psychotherapists for decades to come.

AF: Thank you, Mark. Helping you and others has made my career meaningful. I am very grateful my wise old dad pushed me into psychiatry.