Bias

5 Ways White People Can Interrupt Our Racism

Addressing the fear and embracing justice.

Posted June 27, 2020

1. Know and trust in your own goodness

In conversations around race, White people often exhibit fear and defensiveness. Those who are not overt White supremacists fear being identified as racist or associated with the evil of racism.

A White person responding to a recent post of mine about White fragility described being expected to confess the existence of some hidden, semi-conscious, racist demon inside them. They were confident that in their heart they were not racist at all. I responded that I didn’t think the hearts of White people were very relevant to the question of race.

Racism is a system that denies the oppressed person’s interior experience has any significance at all. That’s the point. The color of one’s skin determines who one is, both internally and externally. For well-meaning White people to point to their good intentions, kind hearts, and justice-oriented thinking in response to the oppressive manifestations and concrete mechanisms of systemic racism, is an aggressive act of the privileged to change the topic from their own complicity to a claim that they are the ones being injured.

All people do, in fact, have an interior life. What is worthy and just in our hearts and minds are often manifest in our external life. Kindness in thought and feeling can shape and motivate our engagement in struggles for justice and mercy in the world. The absence of kindness, mercy, and the valuing of justice within a person will often manifest in a lack of those qualities in social interactions.

However, no amount of goodness within me has stopped me from manifesting insensitivity, selfishness, or fear-based aggression. These interior qualities and values do not exclude misdeeds and even active participation in evil. This is evident in every large-scale atrocity throughout history in which good people have passively and actively supported genocide and other great injustices.

Knowing and trusting your own goodness is not a way to minimize our responsibility for being bystanders through decades of racial oppression and injustice in our country. Rather, it is essential to acknowledging the complexity of that by-standing and addressing it in the future.

An individual White person’s goodness does not prove that they did not participate in racism.

An individual’s participation in racism does not reduce their goodness. Although it certainly delineates its limits, just as an internal orientation that favors anti-racism delineates a distinction between White supremacists and other White folks.

Remember that being a White ally is not about being perfect. It is far more helpful to be increasingly self-aware: confident in your values and good intentions, but not confusing them with innocence.

2. Acknowledge the authority of Black people around racism

It has often been said that humility is a virtue. What is often overlooked is the relationship between humility and humiliation.

Most people believe they know the truth of their own experience and many believe they know a good deal about the experience of others as well. We experience humiliation when we are confronted by the limitations of what we know and believe we know. This kind of humiliation, the bumping up against the limits of our own understanding, is a principal factor in any learning experience. A good student embraces being a student and is not pretending to be the teacher: they are humble. Their humility allows for the possibility of growth. A good teacher is not afraid of exposing the student to humiliation, in this sense, and helps them to experience it, not as an assault, but as a bridge to learning something new.

White people need to be humble students when hearing or witnessing the experience of Black people about race.

The history of racism is humiliating to the well-intended White person. When exposed to that history—our history of racial oppression—we should not strive to counter, minimize, or ignore it, nor distance ourselves with claims of personal innocence. In the moment of acknowledging and feeling our humiliation, we often respond with defensiveness, anger, and tearful expressions of hurt. I am suggesting that we might respond instead by allowing ourselves to be humbled by what our Whiteness actually means in this world. While it might feel like an assault, we need to remember that we are learning. This lesson is one not only for our minds, but also the development of our hearts.

Please note: White people, in the above classroom metaphor, must play both the role of the humble student and that of the courageous, supportive teacher. Our transformation is not the responsibility of Black people. It is ours.

3. Identify your signs of defensiveness

When approaching a discussion about your own humiliation one should expect to get defensive. That’s OK.

Your responsibility, however, is to notice and manage that defensiveness.

Some hints in identifying your defensiveness:

- Becoming angry or aggressive

- Strong reactions to Black people being angry

- Declining to respond to the questions or ideas of others

- Tension in your body

- Crying or feeling victimized by discussion

- Raising the volume and intensity of your voice

- Harsh criticism of others (in thought or word)

- Feeling that no one is hearing you

4. Learn techniques to return to openness

When we are being defensive, whether with aggression or tears, we have closed down and have little availability to dialogue or interaction. Again, that’s OK. Facing and speaking about one’s humiliation is threatening and, therefore, defensiveness is to be expected.

Our responsibility is to return ourselves to a state of openness. We should not expect Black people to take care of us or to back down so we can return to equilibrium.

Some hints for returning to openness:

- Acknowledge your defensive feelings

- Take at least a 30-minute break if your stress is elevated significantly

- Check to see if what you are defending is actually being threatened

- Practice relieving the sensation of tension in your body using breathing or other stress-reduction techniques

- Notice how acknowledging what is true will not mean that you are a bad person

5. Embrace that your primary job as an anti-racist is and will always be identifying and addressing your own racism

The hardest part of my own anti-racism development was embracing two words: My racism.

I clung to several philosophical and political justifications for maintaining a distance from the notion. I called it my insensitivity, my naivete, and my privilege. I could even admit to my biases. But not my racism. I didn’t want to own it. In my last-ditch effort to cling to innocence, I spoke of “my participation in racism.”

But it’s mine.

I did not create it, I do not share its values, I oppose it when and how I can, I am embarrassed by its existence, and I long and I work for its annihilation. I hate it.

But I have racism. I was born into it, I have contributed to it at home, school, and work, in thought and deed, by action and failures to act. I have been paid my whole life by racism in the currency of privilege and I have rarely declined the advantage.

Acceptance of what our skin color means is a door that promises to open to a whole new world. It provides the opportunity to exchange our luxurious isolation for diverse celebration; to abandon exclusivity for community, and to surrender privilege for justice.

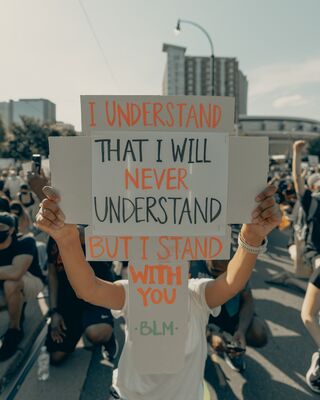

In recent days, the number of White people protesting alongside of their Black brothers and sisters on behalf of equal justice is enough reason to begin to hope.

"Copyright Keith Fadelici"