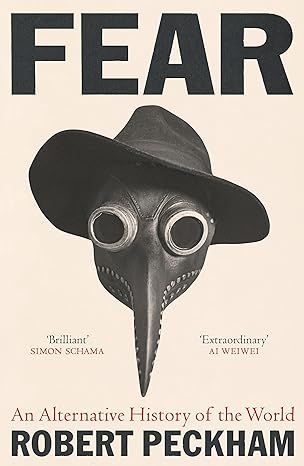

Fear

The History and Psychology of Fear Can Inform Our Future

A conversation with author and professor Robert Peckham.

Posted November 1, 2023 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

For 13 years Robert Peckham was a Professor of History at the University of Hong Kong, as well as the MB Lee Endowed Professor in the Humanities and Medicine. Today he is based in New York City, where he is working to develop an independent think-tank, Open Cube, which brings together the humanities and the sciences to study the social and health implications of transformative new technology. We spoke about how the psychology of fear helps explain our past, present, and future.

What did you learn about the psychology of fear?

Robert Peckham: From the comparative study of cholera, plague, HIV/AIDS, and influenza, I learned fear was more than a psychological response to a specific threat; it was also a response to the many uncertainties that epidemics can reveal and produce. While they often make visible underlying societal tensions, epidemics have destabilizing social, economic, and political effects. Fear of a pathogen can swiftly mutate to fear about social breakdown, financial collapse, threats posed by others, or the erosion of freedom. There may be confusion about causes or transmission pathways. Fear has a fickle, "liquid" quality; its object can easily change. Different fears become entangled in ways that make their individual root causes hard to discern. One could say that fear is plural, even when we think it’s singular.

Fear often involves a process of “othering” where the source of a threat (real or imagined) is attributed to a stigmatized object, person, or social group. Fear can give way to anger, hate, and violence – all of which can be harnessed for political ends. The management of fear is a tricky business, however, often backfiring as new countervailing fears arise that challenge the governing authority. Measures taken to anticipate panic may induce panic, which sparks counter-panics, which then confirm official fears and a set of other panics.

Fear is often viewed as a disruptive force that shatters the collective, but my research suggests the opposite is also true. Individuals can bond through shared fears, which may be instrumental in the formation of new associations. Fear brings us together and tears us apart.

This last aspect of fear had been driven home to me many decades before, when as a student traveling across South Asia in the late 1980s, I got caught up in a terror attack in eastern Afghanistan. Bombs went off, causing death and injury from flying shrapnel. As I ran for my life, I experienced a perplexing sense of simultaneous isolation from and fraternity with the panicking crowd. This traumatic episode highlighted several other psychological aspects of fear, which I would go on to study. I saw how fear could be weaponized as part of a political calculation; how it could be motivational, even thrilling – the sudden threat to life that day gave me new purpose; and finally, how our individual fears are always situated in and shaped by enveloping historical contexts.

What did fear mean to us in the past?

RP: Fear has been understood in different ways in different times and places. Part of my argument is that old fears never go away, they are just reconfigured in new ways. Borrowing from the history of technology, I describe this as a “recombinatory” process where fears are constantly remolded within evolving social and political systems.

A modern Western lexicon of fear took shape in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. At this time, writers and philosophers in Europe began to reflect more systematically on the merits and perils of fear, and the printing press helped to disseminate their work. Niccolò Machiavelli’s treatise The Prince is perhaps the best-known disquisition on the pragmatic use of fear in political life. As he expressed it, “It is better to be feared than loved, if you cannot be both.”

In my book, Fear: An Alternative History of the World, I show why this focus on fear came about. In the mid-fourteenth century, a bubonic plague pandemic killed up to 50 percent of Europe’s population. The social, political, economic, and psychological shocks that this crisis produced were factors in the breakup of Christendom. An incapacity to manage fear – of disease, death, divine judgement, famine, and war – played an important role, not only in the challenge to established authority, but in the consolidation of centralizing states.

During the Reformation and the Wars of Religion, the successful governance of fear became a key justification for power, integral to the state’s bureaucratic machinery. This was also the period that Europeans began to carve out global empires, exporting a fear-based politics with them. It’s this global expansion of Western fear that I set out to explore, recognizing that fear has different meanings in different cultures.

While it’s far easier to study the effects of fear in relation to specific events – say an epidemic, natural disaster, or war – I’m interested in the fears that inhere within and diffuse through social and economic systems: slavery, industrialization, and market capitalism. As a researcher, my focus is on the concatenation of fears that emerge with our modern, globally connected world, and how individuals and communities attempted to understand and make sense of them.

For example, fears coalesced around novel technologies like the telegraph and the telephone. The telegraph, which was viewed as means of rapid communication that could forestall potential threats, soon led to worries that important news could get lost in the flood of data. And worries, too, that it might fuel panic, or that networks would be sabotaged.

During the Industrial Revolution there were those who argued that technology would liberate humans, but there were also those who claimed that it heralded the end of human “civilization.” Fears grew around new dehumanizing industrial processes. There was fear that the individual’s autonomy was being undermined; fear that technology could be misapplied; and worries about industrial accidents. From the invention of writing to the printing press, and from the telegraph to the internet, technology has created new conduits for fear at the same time as it has furnished new opportunities to manage fear. It’s this contradiction within technology that we continue to grapple with today in relation to the internet and fears of an AI takeover.

It’s important to point out that fear can be a catalyst for positive change, since there’s a tendency to look back at the past and imagine that fear, as it has been used politically, is the preserve of the wicked despot. “Benevolent fear” was crucial to social reform in the nineteenth century. When cholera arrived in Europe and North America in the 1830s, it led to widespread panic, triggering riots in some cities. Subsequent epidemics gave urgency to the issue of how to deal with the problem of the urban poor, whose squalid dwellings were viewed with alarm by the wealthy as incubators of contagion and violent crime. It was fear, rather than a humanitarian impulse, I’d argue, that spurred action and secured change.

How can understanding fear help us face the future?

RP: While fear is a neurophysiological phenomenon – involving neural circuits, reflex and cognitive processes – it also has an acquired social and cultural dimension. To an extent, we learn how and what to fear. If we accept that fear is in part enculturated in us, then we concede that it may be possible to “unlearn” our fear. As the psychiatrist Karl Menninger observed in 1927, “Fears are educated into us, and can, if we wish, be educated out.” Understanding where our fears come from puts us in a much better position to evaluate them critically and ultimately to manage and modulate them. This is why history in conjunction with psychology are such vital areas of research.