Narcissism

The One Thing Every Narcissist Craves

... and why some will never believe they've achieved it.

Posted July 30, 2022 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- Two types of narcissism are grandiose narcissism (thick-skinned, extraverted) and vulnerable narcissism (thin-skinned, shame-prone).

- A new study finds grandiose and vulnerable narcissists strongly desire status.

- The new research further finds that grandiose narcissists, but not vulnerable narcissists, believe they have successfully attained status.

Are narcissists born or made? Are narcissists happy? Do narcissistic people’s dominance, self-centeredness, or arrogance hide deep insecurity, guilt, and shame, or do these characteristics reflect high levels of self-confidence, self-esteem, and self-love instead? And can narcissists change?

The above is a sample of common questions about narcissism. Unfortunately, many questions, including “what causes narcissism?” or even “what is narcissism?” are more difficult to answer than they may appear.

One such question is whether narcissists have a strong desire for social inclusion (i.e., being liked, loved, accepted), social status (i.e., being respected, admired, even worshiped), or both. For possible answers, we turn to studies by M. Mahadevan and C. Jordan, published in the May issue of Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

Understanding Narcissism

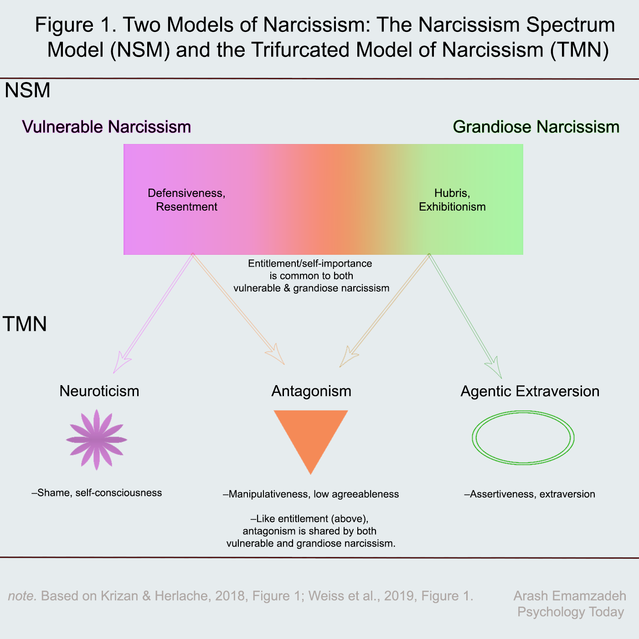

Before we review the methods and findings of the studies, a brief description of two models of narcissism referenced in the paper:

- The narcissism spectrum model. One way of understanding narcissism is to think of narcissism as consisting of grandiose narcissism (overt, thick-skinned, dominant, exhibitionistic, manipulative) and vulnerable narcissism (covert, thin-skinned, anxious, shy). According to this view, the common core of narcissism is a sense of entitlement/self-importance.

- The trifurcated model of narcissism. The second view divides narcissism into three factors: neuroticism (self-conscious, prone to shame), agentic extraversion (socially active, assertive), and antagonism (exploitative, entitled). The model considers antagonism to be the root of narcissism.

See Figure 1.

Investigating Narcissism, Status, and Inclusion

Study 1

Sample: 309 individuals (140 women); the average age of 37 years; mostly White (71 percent).

Measures (example items in parentheses):

- Status aspirations (“I aspire...to be a person of importance and distinction.”)

- Inclusion aspirations (“I desire...to have many friends and close relationships.”)

- Perceived status attainment (“I feel that people see me as an important person.”)

- Perceived inclusion attainment (“I feel that people like me as a person.”)

- Psychological entitlement (“I honestly feel I’m just more deserving than others.”)

- Grandiose narcissism (“I like to look at my body.”)

- Vulnerable narcissism (see below)

Researchers used the vulnerability subscale of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory to assess vulnerable narcissism. The inventory evaluates multiple dimensions of pathological narcissism, such as entitlement rage, exploitativeness, grandiose fantasy, and self-sacrificing self-enhancement. Three dimensions, which evaluate narcissistic vulnerability, were used in the present investigation:

- Contingent self-esteem (“I need others to acknowledge me.”)

- Hiding the self (“It’s hard to show others the weaknesses I feel inside.”)

- Devaluing (“Sometimes I avoid people because I’m concerned they’ll disappoint me.”)

Study 2

This replicates the above but uses different measures of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism.

Sample: 367 individuals (141 women); the average age of 36 years; mostly White (59 percent).

Narcissism measures are described below.

- The Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire: Assesses two aspects of grandiose narcissism, namely, narcissistic admiration (“I am great”) and narcissistic rivalry (“I want my rivals to fail”).

- The Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale: Evaluates vulnerable narcissism (“I am secretly ‘put out’ or annoyed when other people come to me with their troubles, asking me for my time and sympathy”).

- The short version of the Five Factor Narcissism Inventory: Assesses various dimensions of narcissism, like arrogance (“I only associate with people of my caliber”), authoritativeness, need for admiration, shame, reactive anger, distrust, lack of empathy, exhibitionism, exploitativeness, and manipulativeness.

What Grandiose and Vulnerable Narcissists Want

Data analysis indicated that “all underlying components of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism related to a strong desire for status, not only their common components of antagonism or entitlement.”

So, the difference between vulnerable and grandiose narcissism is not that just one type desires climbing social and work hierarchies, achieving status and prestige, and feeling powerful and superior. They both desire that. It is, instead, a matter of which type of narcissist has been successful in achieving what they want. Grandiose narcissists are more likely to say they have; vulnerable narcissists, less so.

What about differences in the desire for inclusion?

The data showed that “grandiose narcissism (and agentic extraversion) related strongly to the desire for status,” but “modestly or not at all to the desire for inclusion.”

Indeed, the only time grandiose narcissists desire inclusion (e.g., being liked and accepted by friends and colleagues) may be when inclusion helps them achieve a higher status. This is not the case for those high in narcissistic neuroticism (vulnerable narcissism). Vulnerable narcissists, the results indicated, desperately wanted to belong and feel accepted by others. Yet, just as with achieving status, they had little success meeting this goal.

Finally, the results show the core of narcissism is more likely antagonism than a sense of entitlement and self-importance.

Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry

These findings may have applications for the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Concept:

To maintain a sense of self as superior, one strategy grandiose narcissists use is agentic extraversion (also called “narcissistic admiration”). Agentic extraversion refers to a tendency toward self-assured assertiveness, self-enhancement, and self-promotion.

When the strategy of agentic extraversion fails (e.g., when self-doubts creep in), narcissists often use the strategy of “narcissistic rivalry.” Narcissistic rivalry, a type of aggressive self-defense, involves maintaining superiority through ruthless competitiveness and belittling others.

What if narcissistic rivalry also fails to protect the person’s status? Then, narcissistic vulnerability might result, leading to pulling out of the competition and focusing on satisfying their need for inclusion and belonging in order to make up for their loss of status (see here for more detail).

Takeaway

All narcissists have a high desire for status.

Grandiose narcissists believe they have attained status already.

Vulnerable narcissists, in contrast, desperately want not just status but also inclusion. Unfortunately for them, they often feel unsuccessful in achieving a high position in life or attaining acceptance and external approval. So, in a way, vulnerable narcissists are failed narcissists.

Facebook image: fizkes/Shutterstock