Trauma

Fight, Flight, Freeze and Withdrawal After Trauma

Part 2: Polyvagal Theory and withdrawal as a secondary autonomic stress cycle.

Posted May 3, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

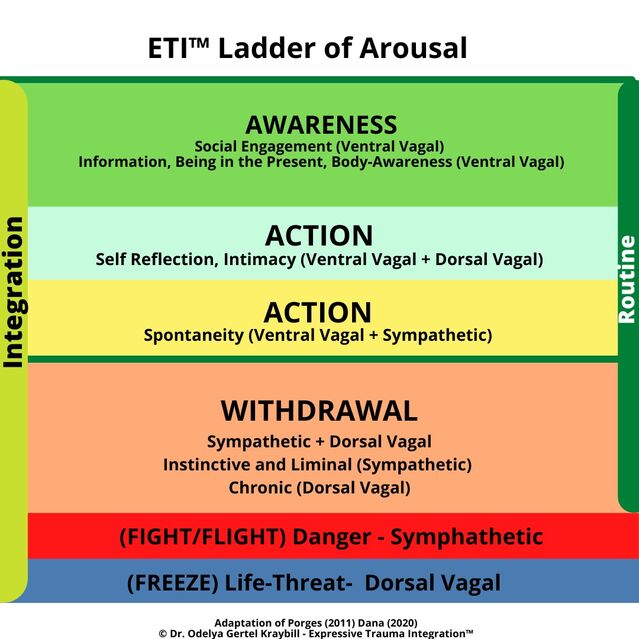

- A third state of stress reaction exists between fight/flight and freeze: Withdrawal. Working with withdrawal lies at the core of trauma therapy.

- Three types of Awareness assist exit from Withdrawal: Awareness of key information, awareness of the present moment, and body awareness.

- Three types of Action, each a mixed state in terms of PLV theory, facilitate trauma integration: Self-reflection, intimacy, and spontaneity.

- Integration involves narrative processing of prior stages and brings an emerging sense of purpose, meaning, and joy in life after trauma.

In my last post, I proposed a third state that exists between fight, flight and freeze extremes: Withdrawal. This in-between state, characterized by troubling episodes of withdrawal, is the reality most trauma therapists face in working with clients. Such withdrawal after trauma is complex, requiring a systemic response. In this post, I present a framework for guiding such a response.

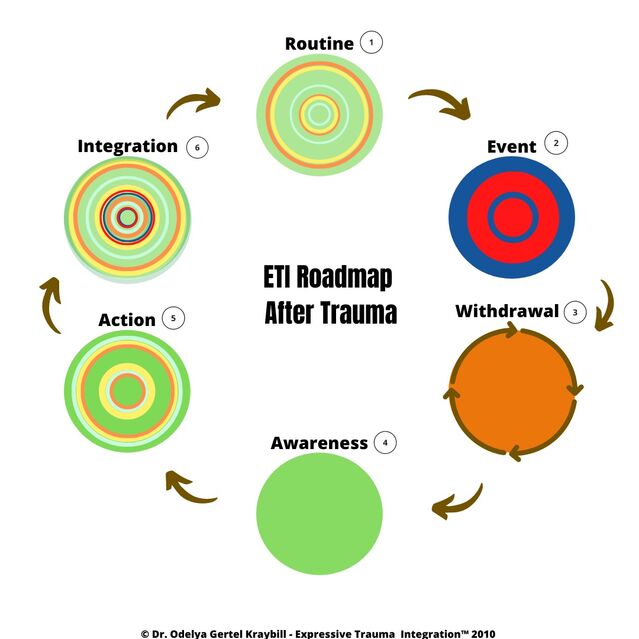

ETI Roadmap After Trauma

In a 2010 essay, I proposed a roadmap for describing what takes place before, during, and after trauma, to serve as a guide for the process of trauma integration. The roadmap describes Withdrawal as a phase in its own right that comes just after a traumatic episode.

It’s important to recognize, however, that withdrawal is not “once and done." Trauma integration is a complex and messy process and survivors go through each phase more than once. Think of a spiral, not a line. The spiral nature of trauma integration is especially important in understanding Withdrawal.

Stage One: Routine

The baseline, before the trauma. Life is characterized by routine without excess highs and lows of any kind.

Stage Two: Event

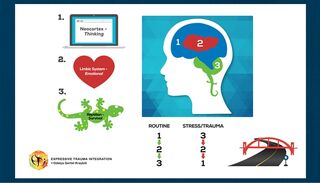

A traumatizing event occurs that triggers defense mechanisms, which take over in the brain and the body. See the description below called a “3-2-1” reaction*.

Stage Three: Secondary Autonomic Stress Cycle

As soon as a traumatic Event passes, most survivors experience a more-or-less irresistible urge to withdraw to a safe, quiet place. Survivors cycle through intense emotions, feelings, and sensations such as shock, fear, anger. Some are gripped by rumination (“shoulda’/coulda’/woulda’”).

Some survivors move beyond this stage before long. Many others experience episodic returns and move on with difficulty. Some seem to remain stuck here.

In its simplest form, Withdrawal is an instinctive and often helpful reaction to threats of almost any kind. Without it, we’d remain in harm’s way. It is so much a part of the way humans are wired to cope with danger and stress that it is basic to our patterns of behavior.

Applying Polyvagal Theory to the concept of Withdrawal, we can recognize three different kinds of withdrawal, and many survivors vacillate back and forth between them:

- Instinctive Withdrawal (Sympathetic + Dorsal Vagal). Moving away from immediate danger is an instinctive, life-giving response. Without this instinct, we’d never remove ourselves from danger.

- Liminal Withdrawal (Sympathetic). This is a later response, long after the immediate threat is gone, that occurs occasionally when anxiety is triggered by specific reminders of trauma. Anything that looks, sounds, smells, or feels like things experienced at the time of trauma can trigger fear that danger has returned. Survival mechanisms respond by taking over the brain, temporarily setting aside logic and reason. Survivors don’t respond to situations they encounter, they react in panic.

Situations of perceived threat can easily trigger this stress reaction and life becomes very hard for survivors. In this state, survivors continue to feel flooded, “on edge," unable to sit still. A sense that danger is at hand lingers. Anger, fear, anxiety, and panic are common, as is difficulty with attention and focus.

- Chronic Withdrawal (Dorsal Vagal). When an individual’s fear response gets triggered over and over again, withdrawal becomes deeply wired into being. This happens when people are exposed to ongoing stress or multiple traumatic experiences, or when they have a history of developmental (early life) trauma. In such circumstances, what began as a temporary reaction takes up permanent occupation in the nervous system, and shows up as numbness, depression, or dissociation (possible DID), as well as complex life patterns built around the resulting dysfunctions. Survivors struggle with a chronic sense of isolation and cycles of shame, guilt, and feelings of worthlessness. They are at high risk for addictions, autoimmune conditions, and other chronic illnesses.

For the most part, withdrawal is a mixed state in which survivors struggle with hyperarousal for a time and then, overwhelmed and exhausted, shift to some variation of stress-arousal. Mixed states can be temporary for some survivors and prolonged for others.

Stage Four: Awareness as Exit From Withdrawal

Awareness engages the upper parts of the brain and enables the resumption of a 1-2-3 state (see ETI psychoeducation image above). From a PLV perspective, this stage engages the Ventral Vagal. In selecting activities for awareness when withdrawal is a big challenge, it’s useful to recognize three different options:

-

Information. Psychoeducation about how trauma affects the brain. This information provides context and assists survivors come to the realization that we don’t get to choose our response to trauma — we react instinctively. That’s an important realization that helps ease the shame and guilt many survivors carry.

- Being in the present. Paying attention to inner and outer signals. This can be tricky since awareness may also trigger uncomfortable feelings, sensations, and thoughts that return the survivor to withdrawal. Expand this awareness slowly!

- Body awareness. This helps the self-regulation of emotions. Learning to detect and trace what is happening in the body, what sensations are associated with particular triggers (sensory stimuli), alerts, movements, postures, etc., lays an essential foundation for self-regulation. This type of awareness is mixed with the Action stage (#4 in the ETI™ Roadmap).

Awareness can't achieve its full impact in moving out of Withdrawal without Action (stage #5), since exiting Withdrawal requires an active decision to engage with self-reflection. A typical flow of therapy might begin Awareness work with psychoeducation about trauma and its impact, then continue with expanded capacity to take action.

Stage Five: Action

Action involves a conscious choice to use resources available to the survivor to act. From a PLV theory perspective, the three kinds of Action usually engage with more than one Vagal pathway, so we should view it as also a mixed state.

Three kinds of actions can be considered:

- Act of Self-Reflection (Ventral Vagal + Dorsal Vagal). Making a conscious choice to recognize and acknowledge resources. It is hard to overstate the degree to which Withdrawal reduces a survivor’s awareness of resources, both their own and those around them, for surviving during and after trauma.

Often just getting out of bed requires great courage for survivors who know they will be greeted with painful reminders of the past. Few survivors recognize the courage, persistence, determination, and perseverance they are displaying hour by hour just to perform the basics of life. Few survivors credit themselves for being creative for trying one thing after another in an attempt to feel better.

Recognizing these resources survivors carry can be an important step in the process of trauma integration. (See this post about redefining resilience.)

While the survivor is still immobilized with withdrawal, she feels safe enough to take action and move ahead in the trauma integration process. In PLV terms, this state is called stillness.

- Experiencing Intimacy (Ventral Vagal + Dorsal Vagal). This state engages the Social Nervous System with the Dorsal Vagal. The ideal strategy is engaging in an attuned relationship, preferably with a therapist, in order to reconnect to (or discover for the first time) the experience of feeling safe in a relationship. The experience of being attuned to in a predictable, repetitive, safe, and loving way is a powerful antidote to Withdrawal. (See this post about Attunement and Love in trauma therapy.)

- Experiencing Spontaneity (Ventral Vagal + Sympathetic). Activities that enhance self-regulation through spontaneity, movement, and sensory integration. Such activities engage the sympathetic nervous system in ways that facilitate self-regulation by expanding the window of tolerance to stress. We continue with this practice until the time seems right for “safe” engagement with the core distress of trauma, using methods of Imaginal Space (spontaneous state of being) in a contained environment. In this state, we also practice engagement with playfulness to enhance spontaneity, what Porges called mobilization without fear.

Stage Six: Integration

Trauma integration is achieved when trauma is acknowledged to be a part of ongoing reality but is no longer at the center of experience for it is now surrounded by awareness of resources for coping with adverse experiences, past and present. (Gertel Kraybill, 2010)

For survivors whose trauma is unprocessed, this stage is likely to be the hardest, since the work here involves accepting that life has moved on.

Feelings of “normality” begin to return. These can lead to letdown when the reality of pain/loss again resurfaces, as it inevitably must. The challenge for the survivor is to build a meaningful life around a new narrative that includes: what existed pre-trauma, the trauma event itself, and thereafter. Integration involves narrative processing of prior stages in a way that highlights the emerging sense of self, personal aspirations, and a definition of purpose, meaning, and joy in life after trauma.

Back to Stage One: Returning to Routines

Stress comes with life. Triggers can’t all be avoided. Survivors will continue to move in and out of withdrawal, even after they have integrated the traumatic event.

The most important antidote to this is living in the present. Survivors have to be proactive about planning and sustaining a life that supports trauma integration. For most, this means they must design and implement a sustainability plan that targets all aspects of wellness (emotional, cognitive, physical, spiritual, and social) to attain sustainability after trauma therapy is over (See this post about the All-Wellness Approach).

The journey after trauma is not a linear one, nor is ETI a linear roadmap. Participants often seem to move back and forth among the stages randomly. Any number of triggers, including even the stress of day-to-day living or the stimulation of excitement at times, can return a survivor to Withdrawal.

Integration includes all stages of the Roadmap: the traumatic event/s, withdrawal, all types of awareness, and action. It does not bring recovery or reversal of all that was lost. A sense of well-being comes and goes. However, with the right kind of systemic intervention, survivors spiral upward over time, and quality of life expands.

*In times of stress, we actually experience a 2-3-2-1 situation since the Limbic system is triggered first and then activates the lower part of the brain, while the upper parts of the brain shut off.

References

Dana, D. (2020). Polyvagal Exercises for Safety and Connection: 50 Client-Centered Practices (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

Gertel Kraybill, O. (2010). Psychodrama and Trauma Integration Model. MA thesis. Lesley University. Natanya/Boston.

Kraybill, R. (1988). From head to heart: The cycle of reconciliation. Conciliation Quarterly, 7(4), 2-3.

MacLean, P. D. (1985). Brain evolution relating to family, play, and the separation call. Archives of general psychiatry, 42(4), 405-417.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

Siegel, D. J. (1999). The developing mind: Toward a neurobiology of interpersonal experience. Guilford Press.