Trauma

The Neuroscience of Gratitude and Trauma

Attempts to be positive do not expand capacity to endure pain.

Posted January 31, 2020 Reviewed by Chloe Williams

We all know this encouraging expression: "Think positive." People say it with kind intentions, but is it helpful advice?

With trauma survivors, there is good reason to avoid such expressions. Why? The answer requires us to examine the neuroscience of the survival mechanism after trauma.

What Happens After Fight/Flight/Freeze?

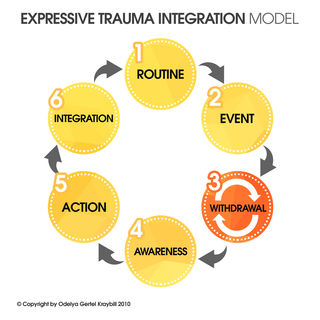

During trauma, people instinctively go into a stress response. The fight/flight/freeze mechanism is triggered, so they are going to do one of those three things. (In the ETI roadmap, this is Stage Two).

When the traumatic event has passed, the trauma trigger remains. The individual can easily be re-triggered to feel the danger has returned by things that look, sound, smell, or feel like things experienced at the time of trauma.

As a result, many survivors feel “on edge” all the time. A feeling that terrible danger is at hand haunts them everywhere they go. This chronic sense of danger often activates a withdrawal response (Stage Three in the ETI roadmap).

It’s important that survivors and caregivers understand withdrawal—its purpose and why it lingers. Universally among survivors, as soon as a traumatic event is past, they experience a powerful urge to withdraw to safety and rest. Withdrawal is a useful, life-preserving response that reduces vulnerability to further injury. It causes people to seek safety, to rest and recuperate after a shocking experience.

However, at some point, this life-preserving response can turn into a cycle of misery. In withdrawal, survivors remove themselves from active engagement with life and other people. They cycle through intense emotions typical after trauma, such as shock, fear, anger, denial, rumination. Later, more complex emotions emerge such as shame, guilt, and a sense of moral injury. Often these show up in the form of endless rumination on “shoulda’/coulda’/woulda.’”

Some survivors are able to move beyond this stage before long. But most have a hard time moving beyond withdrawal. Many remain trapped in it for a long time. For some, withdrawal lasts a lifetime (read this blog about the way out of withdrawal).

For those who experience severe stress and/or trauma at a young age, withdrawal is so much a part of their experience of life that it seems to them a given of reality. Such survivors develop from a young age a sense of shame and guilt rooted in a sense of not being good enough.

After all, young children depend on adults to survive. They tend to blame themselves for their pain responses. It is natural for them to feel “something must be wrong with me.”

When Instincts Help Us Survive But Not to Thrive

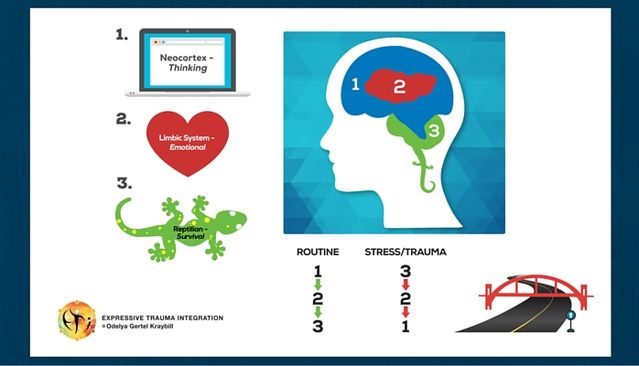

When our fear response is activated, we don’t respond to situations we encounter, we react. Survival mechanisms take over the brain and temporarily set aside logic and reason.

When people are exposed to ongoing stress or multiple traumatic experiences, the fear response gets triggered over and over again. A response meant to be temporary takes up more or less permanent occupation in the nervous system. In this state of hyper-alertness, non-threatening situations of many kinds can easily trigger a fear reaction. Life becomes very hard for such survivors.

So what is the way out?

Awareness is a Way Out of Withdrawal

Awareness helps us engage the upper brain, the part of the brain that is over-run when fear responses are running amok. Three types of awareness are particularly useful in moving beyond the hair-trigger reactivity that troubles survivors in the withdrawal stage. (Withdrawal stage #3 in the ETI roadmap).

- Information about how trauma affects the brain. See my blog post on psychoeducation for more on this.

- Being in the present. In trauma therapy, we do this by helping survivors to pay attention to their inner and outer signals. This can be tricky since awareness may also trigger uncomfortable feelings, sensations, and thoughts that take us right back to withdrawal. Expand awareness slowly!

- Body awareness. This helps self-regulation of emotions. Learning to detect and trace what is happening in the body, what sensations are associated with particular triggers (sensory stimuli), alerts, movements, postures, etc., lays an essential foundation for managing emotional responses.

See this blog post for more information and examples.

You Don’t Have to be Grateful to Improve Your Mental Health

With the above in mind, let's now return to the question of gratitude and positive thinking. We experience gratitude when we recognize goodness in our life and goodness in others and the world.

Gratitude can be very beneficial when it is possible. However, while some trauma survivors can benefit from gratitude, for most it is challenging. The reason has to do with an overactive nervous system. For many survivors, the reactive part of the brain is in charge much of the time (3-2-1). The responsive, proactive, concept-oriented part of the brain (1-2-3), the part of the brain that initiates gratitude, may be mostly on the sidelines.

The difficulty of engaging in exercises requiring robust involvement of the upper brain (1-2-3) leaves many trauma survivors feeling even more inadequate.

This is not because they do not try—or do not want—to be positive. Their hyperactive nervous system holds them in a constant state of anxious reactiveness. The pain of trauma has left them feeling “not good enough,” ashamed, guilty, injured, and unworthy. Their upper brain is not engaged enough to overcome those feelings and contemplate gratitude on an on-going basis.

One study suggests that there’s another way to get the rewards commonly associated with gratitude. In 2018, Wong et al. conducted the first positive psychological adjunctive intervention for psychotherapy clients. About 293 adults who were receiving university-based psychotherapy participated in a study and were randomly assigned to three groups:

- A control group that received only psychotherapy.

- A psychotherapy group that also did plus expressive writing focusing on expressing their deepest thoughts and feelings about stressful experiences.

- A psychotherapy group that also did gratitude by writing letters expressing gratitude to others.

At week 4 and week 12 after doing their first writing work, the gratitude writing group reported better mental health than those who were assigned to expressive writing and to the psychotherapy only group.

The authors found, however, that it was not positive self-expression towards oneself or others that made an impact on the participants’ mental health.

It was refraining from the use of negative emotion words that explained the difference in mental health between the gratitude writing group and the expressive writing group (Wong et al., 2018).

The Key is Not to Try and Change How You Feel

Trying to change how we feel creates a signal that something needs to be changed or fixed in us. This signal is itself so stressful that it can activate the survival mechanism and put us right back into withdrawal.

It is natural of course to want to be positive. None of us wants to feel fear, pain, or anything else that is uncomfortable. But pain and sadness are an unavoidable part of life. They are here to stay. The idea is not to try to change that reality but to expand our capacity to endure it.

How Do We Expand the Capacity to Endure Pain?

Compassion is feeling kindness towards others and empathy for what they are feeling. Self-compassion is feeling kindness towards oneself. Neff (2003) describes self-compassion as “an emotionally positive self-attitude that [can] protect against the negative consequences of self-judgment, isolation, and rumination (such as depression)” (p. 85).

Neff suggests a three-fold strategy to activate self-compassion:

(a) self-kindness—being kind towards oneself instead of self-judging,

(b) focusing on common humanity—perceiving one’s experiences as part of the larger human experience rather than as separating and isolating, and

(c) mindfulness—holding painful thoughts and feelings in balanced awareness rather than over-identifying with them (Neff, 2003. p. 85).

Germer and Neff (2015) suggest the following exercise to experience and build self-compassion:

- Think of a situation in your life that is difficult, that is causing you stress. Call the situation to mind, and see if you can actually feel the stress and emotional discomfort in your body.

- Now, say to yourself:

-This is a moment of suffering (mindfulness)

-Suffering is a part of life (common humanity)

-May I be kind to myself at this moment (self-kindness)

Or: May I give myself the compassion that I need, or May I learn to accept myself as I am, or May I forgive myself, or May I be patient, or May I be xxxxx.

Expanding the Capacity to Endure Pain

As a trauma therapist and trauma survivor myself, I find self-compassion to be one of the most valuable and difficult practices.

Self-compassion is not about being grateful for everything that is happening to you, nor is it about pitying yourself about your injuries. Rather, it is about getting attuned to how you feel and honoring that feeling, as you are able, without self-judgment.

For the reasons described above, for trauma survivors, positive engagement with oneself is difficult, especially self-kindness. It is difficult for survivors not to judge themselves for all the things they wish they could have or should have done differently. The instinct to want to change, to be “better,” to be “fixed,” dominates the thoughts of many survivors. It manifests as an ongoing self-critique and often interferes with survivors’ relationships with others.

The way to expand the capacity to endure pain begins with being open to not being open.

Try NOT to change how you feel, think, or sense things.

Begin by observing what you are experiencing, whatever stuckness, whatever fearfulness, whatever anxiety or withdrawal, without evaluation.

Symbolically, consider this as a research project. Without trying to change anything, gather data on your senses, reactions, and responses.

Simplified self-compassion:

- As a general rule, remind yourself that you are ALWAYS doing the best that you can at any given moment. Given a choice, you may have responded differently to events at the time of the trauma. But you couldn't. Survival mechanisms took over and helped you do whatever it took to stay alive.

- When you are able not to try and change how you feel, you “expand” your response to what you are feeling. When you criticize yourself you “contract.”

- When it is difficult and painful say: “It’s ok to feel pain, it’s ok to feel xxx” “I don’t like to feel xxx but it is ok to feel xxx.” Saying this helps your nervous system calm down. The more you do it, the more your ability to relax by choice expands.

ETI Simplified Self-Compassion Exercise:

- Think of a situation in your life that is distressing.

- Ask yourself:

(1) What do I feel right now xxxx (awareness—recognizing the feeling)?

(2) Rate on a scale of 1-10: How much do you feel this xxxx feeling (1 little – 10 a lot)? - Say to yourself:

(3) xxxx is a part of life, everybody feels like this sometimes (common humanity).

(4) It is ok, I am ok. I am xxxx (your name), I am here, I am now, right now I am safe. - Check in again with the scale of 1-10 to describe how much you feel xxx.

- Repeat until you get to 5 and under.

This introductory exercise is a good way to experiment with self-compassion and expand your capacity to endure pain. Increased ability to live with pain will result in an increased ability to experience joy. The process of trauma integration should target all aspects of wellness (emotional, cognitive, physical, spiritual, and social). Over time, you will gradually feel less vulnerable to extremes of highs and lows, and experience an overall sense of sustainability (read more about sustainability on this blog).

References

Germer, C. K., & Neff, K. D. (2015). Cultivating self-compassion in trauma survivors. Mindfulness-oriented interventions for trauma: Integrating contemplative practices, 43-58.

Neff, K. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and identity, 2(2), 85-101.

Wong, Y. J., Owen, J., Gabana, N. T., Brown, J. W., McInnis, S., Toth, P., & Gilman, L. (2018). Does gratitude writing improve the mental health of psychotherapy clients? Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy Research, 28(2), 192-202.