Happiness

Happiness Is Not a Destination

Mental Health Response Sometimes Make Things Worse. Time for a Paradigm Shift

Posted March 30, 2019

Like others, I read social media posts, magazines, and websites on trauma, personal growth, self-care and more. From all sides I am bombarded with techniques and tools on how to be happy, feel good, fulfil my potential, become resilient (see blog) and successful and more.

Truthfully, rather than being inspired and uplifted, I often feel discouraged and upset when I read these pieces. Why?

I tried a lot of that stuff. Tried hard. Some things helped for a little while but nothing worked for very long. I might feel better for a few days or weeks, but then I couldn’t sustain the feeling.

After many years of trying, contemplating, being in therapy, expanding my introspect, I finally began to question my expectations of happiness and realized that I needed to figure out a definition that is achievable for me.

To be happy has a unique meaning for each of us. But one thing it does not mean is to live without pain!

Happiness is not a destination

In the great chase for happiness that pervades much of today’s thinking, it has come to be understood as a destination, a place we can go and reside if we figure out the magic formula for getting there. “If and when I get that XXX (job/partner/desired weight/house…) then I will be happy!”

But in fact, happiness (however you define it) is a temporary state, one of many on a spectrum of states and feelings that come and go. Whatever we call it, being in such a state does not mean that our pain is gone for good. Underneath it all we all carry a “bag” of pain, that goes with us everywhere, whether we remember and notice it or not, whether we direct our attention away from it, or deny it. Pain and sadness is part of life. It’s here to stay.

Millions of people are doing their best to get to a destination that doesn’t exist, at least not in the form they imagine. So the quest itself, and the fact we are not getting “there” becomes a source of misery.

It keeps us feeling that “we are not good enough”. It dooms us to endless comparing of our ordinary selves to someone else’s extraordinary, perfect social media moment. Bombarded with flashes of the peak moments of others how could we not feel that everyone else is better than us, more successful, more socially desirable,, and of course, happier?

Living in a gap between imagination and reality creates a lot of pain. People turn to all kinds of tactics to survive. Some present the world with a facade of cheerfulness. Others enslave themselves to a drive for material success, or try to anesthetize their pain with “diversionary tactics” (see blog).

For me, the quest and the many things I tried eventually brought me to a different understanding of what to expect of life and the reality of painful experiences.

Like many others I sought professional help, and ended up in therapy. I came into this with the most common obstacle to growth, the expectation that there is some magic “pill” (therapist, modality, technique, medication etc.) out there that would take pain away.

It took me years of repeated disappointment to figure out that healers of all kinds, including many therapists, are themselves trapped in the magical thinking that drives many people to seek out therapy. With promises of full recovery, healing, reversal of experiences, etc., many talk shows, blogs, and magazines hold out hopes that are irresistible to people in great pain.

How did we get here?

How did therapy come to be understood by many as a medium to find happiness?

How did it become normal to expect that one methodology or another would be enough to truly help people get better, especially survivors of trauma?

How did we come to think that taking a pill, perhaps with psychotherapy or perhaps not, is a sufficient response to mental health symptoms?

At the heart of much of the “magical” thinking I describe above is a simplistic understanding of mental health, regarding both causes of problems and solutions to them. In this view, mental health symptoms are rooted in past trauma (see blog), often not even recognized as such.

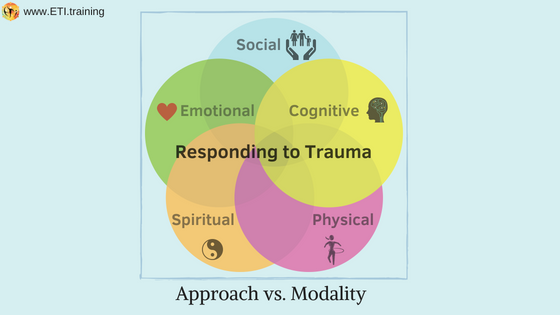

To respond effectively to the injury of trauma, it is crucial to recognize that it deeply affects many aspects of being: (1) Cognitively (ability to process thoughts and make good judgments; (2) Physically (affects our muscles, joints, metabolism, temperature, sleep immune system appetite and weight, etc.; (3) Emotionally (feelings of shame, guilt, sadness, fear, anger, pain) (4) Spiritually (affects our worldview, our understanding and meaning of life, society, and the world; and (5) Socially (affects our relationships with spouses, family, friends, colleagues and strangers.

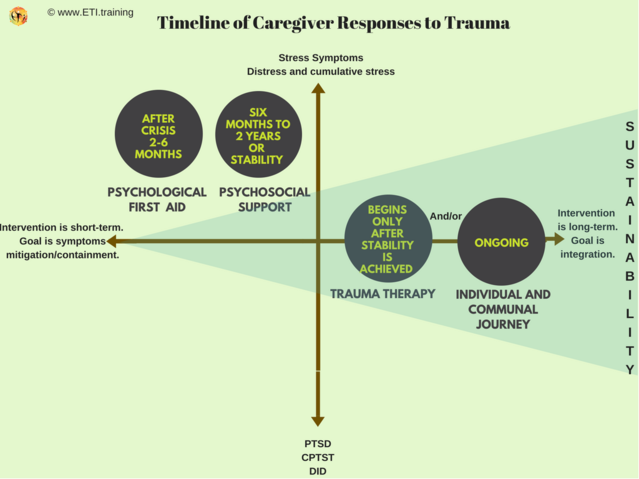

Complex injury requires complex response. From the moment a critical incident takes place until a trauma survivor gets to trauma therapy responses should target all aspects of wellness (cognitive, emotional, physical, spiritual, and social). See blog.

My experience with trauma as a survivor and therapist has made it clear to me that survivors are best assisted by realistic expectations of what can be achieved, and that these expectation are more limited than many therapists seem to suggest to clients. With only rare exceptions, I find clients relieved to engage in a conversation that helps them define realistic expectations for their work in therapy and beyond.

Defining realistic expectations doesn’t bring magical results, of course. In fact, it brings its own challenges as clients turn their attention to things that may seem mundane or even disappointing compared to the “bright stars” expectations that may have carried them for a long time.

Realistic objectives of trauma therapy in my view are: (1) symptoms mitigation - reduction in post trauma stress symptoms and increased capacity to self-regulate ; (2) expanded ability to endure pain and loss caused by the trauma and its aftermath; (3) increased capacity to self-sustain and experience joy with self and others.

The components of an All-Wellness Response include:

-In response to critical incidents – provision of psychological first aid (see blog).

-Appropriate psychoeducation – by providing information about trauma and its instinctual mechanisms and impacts on all aspects of living (see blog).

-Expanding capacity to self-regulate by using appropriate techniques and tools that fit each survivor individually (see blog).

-If developmental trauma is part of the picture, using a secure-attunement framework (see blog).

-Designing and implementing a self-sustainability plan (see blog). A self-sustainability plan is a comprehensive individual program for wellness that has features to address the brain-gut connection (nutrition), inflammation, immune system, stress symptoms, sleep, rest, and exercise, brain training, self-compassion, and social engagement.

I wish you well in finding resources within you and around you to create a set of responses and strategies that address all these aspects. I wish for you to define for yourself what it means and does not mean to be happy!