Sleep

Why Weight? Go to Sleep!

When you snooze, you really do lose.

Posted October 13, 2019 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

This is the first installment of "The Sleep Suite," a six-part series of posts on sleep, aging, and wellness. Each will include practical takeaways intended to optimize your physical and psychological health.

Your bed, a treadmill? Kind of. Does that sound as sweet of a dream to you as it does to me?

Turns out, I haven’t exactly exaggerated the analogy: If you want to lose some inches around your waistline, try getting some more z’s. But not too many: growing research implicates both too little or too much sleep for elevated body mass index (BMI) and obesity. It appears to depend on age.

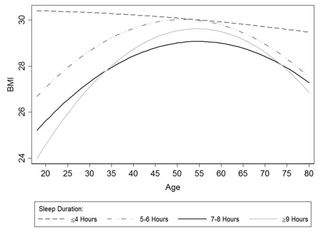

In young adults, the relationship between sleep duration and BMI looks pretty linear: More sleep predicts lower BMI. But this association progresses into a slightly U-shaped relationship during middle age, when both “short” and “long” sleepers show higher BMIs. More complicated still, among the oldest adults, the link between sleep duration and BMI weakens, except that the oldest, shortest sleepers have the highest BMIs of all other age groups.

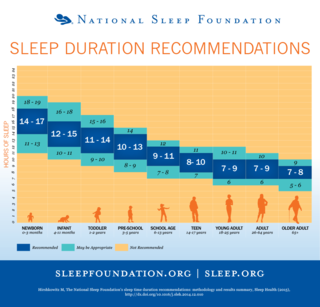

So how much do we need to snooze to lose? The recommended “dose” of sleep again depends on age. Newborns take the cake for requiring the most—14 to 17 hours— while adults aged 26 to 64 need 7 to 9 hours, and adults 65+, 7 to 8. Too little (<5 hours) constitutes sleep deprivation but too much appears counterproductive.

However the relationship looks exactly, the research generally agrees: For a lower BMI— don’t weight, go to sleep. Five empirical reasons may explain why:

-

More time awake means more time to eat. The longer you stay up, the more opportunities you have to eat. Adults experimentally restricted to one hour and 20 minutes of less sleep than controls consumed 559 more calories per day than their counterparts, whose intake decreased by 118 calories. The volume and density of our food also appear to increase over the day, with a majority (>35 percent) of calories consumed after 6 p.m. and a higher percentage of them derived from fat during late-night versus daytime or early evening hours.

-

The energy your body doesn’t get from sleeping, it seeks in eating calorically-dense, highly palatable foods. Because in its continuous striving for energetic homeostasis, the body compensates for sleep deprivation with excessive caloric intake, which explains why you probably didn’t binge on arugula during your last all-nighter. In experimental studies of sleep restriction with subsequent ad libitum feeding opportunity (buffet meals and snacks), sleep-deprived adults not only tend to consume more food overall, but they also eat more carbs, sweets, and saturated fats than controls. Epidemiological studies mirror these experimental data: “Normal sleepers” (7-8 hrs) consume more dietary fiber than short ones (5-6hrs) who eat more calories more frequently from fat and refined carbohydrates, driving insulin resistance in these sleepers.

-

Orexigenic and anorexigenic hormones get dysregulated, promoting weight gain. Under-sleeping may dysregulate two key opposing hormones in appetite regulation: leptin, an appetite-suppressant (anorexigenic), and ghrelin, an appetite-simulant (orexigenic). Morning, fasting blood samples taken from participants following a night of habitual short (5 hr) vs long sleep (8 hr) had reduced leptin and elevated ghrelin levels, a combination often (but not always) co-occurring with hyperphagia, or increases in hunger and appetite. Sleep deprivation may also drive hypercortisolemia and other forms of systemic inflammation, implicated in cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and impulsive behaviors, such as emotional eating.

-

We behave more impulsively with insufficient sleep. Sleep loss may selectively (de)activate brain regions implicated in emotionality and impulsivity. In one study, sleep-deprived adults exhibited a +60 percent greater magnitude of amygdala reactivity in response to negatively-valenced stimuli than controls. And when compared to their non-sleep-deprived counterparts on fMRI, these adults demonstrated significant functional dysconnectivity between the amygdala— our emotional processing hub — and the medial prefrontal cortex, which contributes to impulse inhibition. That means when the integrity of this connection gets compromised after a poor night’s sleep, obesogenic cues (e.g. that chocolate bar taunting you at check-out, the intoxicating scent of fries at the airport) may feel more salient and difficult to resist.

-

Fatigue depletes our motivation. Daytime fatigue secondary to insufficient or poor sleep can hijack our motivation to engage in healthy behaviors, including preparing our own meals, initiating, and/or maintaining physical activities. Short (vs. long) sleep duration predicted more fast food consumption in one study, and briefer, less vigorous next-day exercise in another, as examples. And this cycle can quickly get vicious: over time, reduced activity can promote deconditioning and excessive weight – the biggest risk factor for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)—itself a major driver of daytime fatigue.

Not convinced? Sleep on it.