Coronavirus Disease 2019

Has Pandemic Fatigue Got You Down?

Big-brained mammals don't do well under captivity.

Posted December 11, 2020 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

I have always hated being constrained in my movements for any reason whatsoever—illness, injury, consecutive days of horrible weather, a social obligation—anything that kept me from going out and doing what I wanted to do when I wanted to do it. But when rolling lockdowns began last March to combat the rising COVID-19 pandemic, I joined in, despite my predilections and my doubts that they would work.

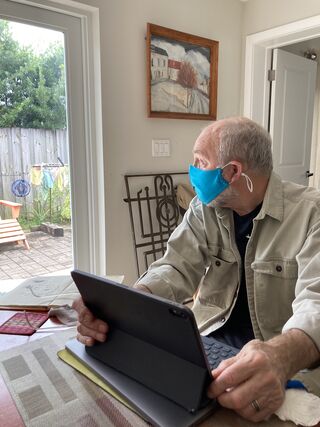

Ever-growing numbers of cases and deaths compiled daily by researchers at Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health confirmed my doubts that enough people would sacrifice their own freedom of movement for the greater good. As two weeks stretched to one month and then nine months, with one year rounding for home at warp speed and the much-anticipated vaccines closing from behind, we are still being told to wash our hands obsessively, wear face masks, and practice social distancing.

Like many of my fellow world citizens, I like to say that I self-incarcerated fully aware that my sentence was open-ended. I didn’t expect any real issues because, after all, I have been working from home for more than 20 years as a writer, which at times is not the most social of occupations. But I was, in fact, not prepared for the ennui that began to engulf me as the months ground on. There is a qualitative difference between isolation by choice and not being able to spontaneously hug people or see them up close and personal. This is the condition people have dubbed “pandemic fatigue,” a weariness with continued social isolation.

I searched for some explanation of this oppressive feeling and then last month saw Marc Bekoff’s blog posting on the damage captivity wreaks on the brains of big mammals. They suffer physical and psychological effects, among them increased aggression and self-mutilation, pacing, and head-butting. Rhinos have been known to grind their horn down to the nub. Although not all animals have been studied, it has been shown that elephants especially suffer. A chief reason for this is that the animals are severely restricted in their ability to wander and to have social contact with members of their own family group. The effects of being penned on orcas and other marine mammals are well-documented. Neuroscientist Bob Jacobs at Colorado College has been studying the brains of mammals in captivity and has found that “living in an impoverished, stressful captive environment physically damages the brain.”

Among the many changes that the pandemic has caused has been, it seems to me, a growing recognition that, as Firesign Theater noted, we are all “bozos on this bus.” Humans are not the exceptional beings we have sometimes thought ourselves to be.

As I reflected on my growing ennui and Bekoff’s post, I thought: Why not recognize that Homo sapiens sapiens is just another large, big-brained mammal. Why should we expect that we would not suffer ill effects of captivity even if for some of us (in our city apartments or country retreats) it is luxurious by any measure? We are by our nature wanderers and high social animals. Our forebears evolved following big game in their great migrations—as the Sámi notably still do. Thanks to the coronavirus, we are largely constrained from wandering, and that no doubt has ill effects. Some of us may turn out to have suffered neurological damages.

We’re told the pandemic will end, but each day it doesn’t adds to the neurological toll. A recent survey in Psychiatry Research by Singh et al. pointed to the need for long-term follow-up on the impacts of the pandemic lockdown on children and adolescents. It will be useful as well to include studies on adults, as it may turn out that there is little difference to our brains between forced and voluntary incarceration. Those studies might well incorporate for comparative purposes non-human animals who suffer no less than we.

In addition, we will want to consider the plight of dogs, record numbers of which have been adopted during this time to provide companionship to locked down families or individuals. It’s time to reexamine the practice of crating. This past summer, Germany implemented new regulations under the Hundeverordnung, or Dogs Act, to limit the number of hours dogs could be confined to crates and mandating that they be exercised twice a day for an hour total. It would also ban the practice of tethering dogs on a fixed length of chain or rope. These new rules seem bare minimum requirements, but are a welcome step and should become a model for other countries, including the U.S.

As the most recent example of the types of catastrophes that will periodically erupt in the age of human-induced global climate change, the pandemic forcefully reminds us that we have not taken care of our planet. All life is connected and is indeed fragile. Independent scientist James Lovelock warned more than 30 years ago that the Earth, in the guise of Gaia, would rise up and reject the virus that humans have become.