Psychiatry

Psychology In Poetry: In Conversation With Sandra McPherson

Insights into psychiatric institutionalization as seen through a poet's lens

Posted April 13, 2022 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

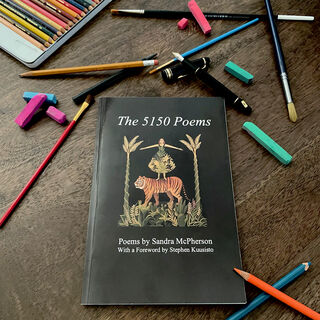

Sandra McPherson is the acclaimed author of 21 books of poetry, including the National Book Award-nominated The Year of My Birth, and her latest, The 5150 Poems (Nine Mile Press). She is a retired poetry professor from UC Davis and was mentored by Elizabeth Bishop. Adrienne Rich called her "a master of the unexpected" and Annie Dillard said Sandra has "a miner's eye for translucent color in the earth and a painter's eye for the 'hard catchable light' in the air."

Through Dillard's praise, we enter into McPherson's mastery of visual art through the printed word. She is, without question, an artist. But just how does her black and white produce such vivid color? How do words grasp our wrists and lead us into someone else's lived experience, as though stepping over the threshold of a painter's canvas? Why are we observers so transfixed by the creative impressions of the others? Compelled by empathy, revulsion, voyeurism, beauty, or even the generated impulse to write—to make some sense of the light and shadow in our own lives. Perhaps releasing our work into the ether in that time-honored tradition of inviting others into our inner world, as though the act of release closes a chapter and allows us to move forward with renewal.

In The 5150 Poems, we're invited behind the doors of psychiatric institutionalization, and how that sightline translated into McPherson's poetics. In California, where McPherson has lived most of her life, 5150 refers to "the number of the section of the Welfare and Institutions Code, which allows an adult who is experiencing a mental health crisis to be involuntarily detained for a 72-hour psychiatric hospitalization when evaluated to be a danger to others, or to himself or herself, or gravely disabled."

We learn the seeds for this collection were planted while the poet was involuntarily detained in a psychiatric ward. While there, she explains, she lived and observed impressions, recollections, correlations, and "shocks" that would later become section one of the book: "Glass Bead Notebook."

Take, for example, a thought fragment that begins, "Valentine's nap:"

Smell the new lumber—contractor-built house—the mirror in my built-in sunken treasure cabinet, box of chocolates kept in the bottom drawer to make them last, then little worms grew in them, end-tables aside my double bed, book of poems I hand-wrote, in a maple drawer, parents' love letters saved up top their linen cupboard...

Although it's a fragmented recollection of her childhood, we read it in the context of her institutionalization. A place of strange beds, missing comforts, and disorientation. Is her recollection a mechanism for her mind to find a foothold in a former reality that felt safe and grounded? Does our mind, through writing and art, attempt to stitch together fragments of our past and present to codify a memory that has been shattered by trauma?

With questions like these arising out of a poetry collection, we see the value of poetry as medical humanities. How a poetry book like The 5150 Poems can serve as a case study and textbook. How writing, as a therapeutic tool, offers deep insight for both patient and practitioner. Modern texts such as Poetry in the Clinic (Alan Bleakley and Shane Neilson) and Poetry Therapy: Theory and Practice (Nicholas Mazza) ask us to consider just that.

Mazza writes, "It is common knowledge that psychology is both an art and a science. The depth of human experience (cognitive, affective, and behavioral domains) is best addressed by drawing from the humanities and sciences... Poetry therapy, as one of the expressive arts therapies, includes attention to verbal and nonverbal behavior, language, symbolism, use of sensory modes, vision, order, and balance (Mazza, 1988)."

Utilizing The 5150 Poems as a medical humanities text one could, for example, examine the repetitive symbolism of beds and pillows. Readers get the sense of proximity to other patients—a barrage of fragmented language and noise—with beds serving as their only location for ownership of space. At the end of section two, she writes:

In my case, I had no choice—

they'd send police.

I gripped

their Reader's Digest condensed book

of a bed.

I've never met McPherson in person. One year pre-Covid, long after her time in the hospital, she contacted me about a doll I was selling online–inquiring about its maker. This year she shared the news of her new book release and, upon savoring its 70 pages in one sitting, I asked if I could talk to her about its importance. Not just as an evolution in her poetic canon but as a teaching tool. How did The 5150 Poems assemble? What is it telling us about mental health and the mental health system?

She writes about her poetry practice: "I never stop; I'm always writing, in my head or on paper or screen. I feel words physically in my brain, and I feel a duty to work on what might be called the art of understanding. From the time I had to write with my newborn on the bed with me—to mother and write simultaneously—I've been note-taking in marshes, restaurants, and so on. Using poetry to write my mental health narrative allowed me to visit various poetics—the fragment, the character portrait, the sort-of-stream of consciousness in "Five Leaves Left"—to explore my changing states of mind."

"Five Leaves Left" is the final section of the book. And after sitting beside McPherson in the psychiatric facility—the shouting, bandages, pills, and recycled air—we are breathing again. The windows are flung open with a view of the trees in a return to McPherson's classic sensory travelogue of music, color, and nature:

"Clear sky over loose birches

head pillowed

in the middle

of Bach

a severethunderstorm

warning

concerto #6

get out of the water

if you hear thunder

Here, the writer works in consciousness and contrast. Loud and soothing, soft and sharp, danger and safety; engendering an expansive sense of place beyond the confines of the psychiatric bed. As practitioners or students of her work, we might get the sense that she is feeling more grounded, living in the present with a renewed agency and purpose, yet wary of where the storms of life can take us. A return to her poetic form, but fresh with curiosity, zest, and grace—utility released by fragmentation and time's passage. We don't presume a finality to the healing of trauma; but through the shift in tone, form, and imagery, we are gifted with an intimate invitation to witness a thriving, curious, being, life-in-progress. And "in-progress" is all of us.