Relationships

Sex, Love, and Machines

How artificial intelligence (AI) could redefine relationships.

Posted April 12, 2022 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- AI technologies are being used to build machines that provide human companionship.

- In the coming decades, humans could turn to machines for sexual and emotional intimacy.

- Now is the time to consider what human-machine relationships will look like in the future.

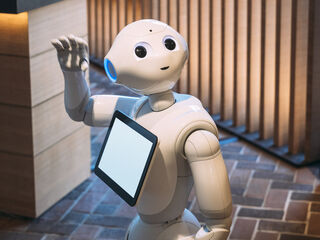

In the plot of Spike Jonze’s Her, the main character, Theodore, falls in love with Samantha, an AI assistant depicted only as a voice coming from his computer. While the premise of the film may seem far-fetched to some, it raises an intriguing question: What does it look like when people form attachments to AI technologies like social robots and chatbots? The evidence is compelling that human relationships with machines are not only possible, but may soon be inevitable.

Machines as Sexual Companions

One place to begin searching for answers about the future of human-machine relationships is in the sex industry, which is a historically good gauge of where technology is headed. In 2000, a man by the name of Davecat became the focus of intense academic and media interest when he began a relationship with (and later married) his sex doll, Sidore. Today, some sex dolls are AI-enhanced to make them more life-like, which could further encourage their use as human companions. A new essay by Marco Dehnert, a graduate student in the Relationships and Technology Lab at Arizona State University, dives deeper into the controversial topic of sex robots and what they could mean for relationships between humans and machines.

Machines for Love and Intimacy

In his book Love and Sex With Robots, David Levy predicts that by 2050, humans will turn to AI for not only sex, but also love. Machines are already being trained in social skills and even emotional intelligence to make them more responsive to human needs. And if it seems unlikely that this could lead to something resembling an intimate relationship, consider the possibilities presented by an AI that can pass the Turing test – where talking to it is indistinguishable from interacting with another human. These sorts of AI technologies will be there to assist their owners while requiring nothing of them in return, making them natural targets for human affection.

Looking Ahead: The Future of Human-Machine Intimacy

What will a future of human-machine relationships look like? The time to start thinking seriously about this question is now. Just this past year, the San Francisco Chronicle reported on a man named Joshua who built a custom chatbot to simulate his late fiancé, Jessica, who passed away from a rare liver disease when she was only 23 years old. The chatbot service – Project December – is powered by GPT-3, a highly sophisticated text-generating algorithm created by OpenAI. It was never intended to simulate real people. As AI technologies become more ubiquitous in everyday life, it will be important to anticipate their potential human uses and effects on relationships.

References

Dehnert, M. (2022). Sex with robots and human-machine sexualities: Encounters between human-machine communication and sexuality studies. Human-Machine Communication, 4, 131-150. https://doi.org/10.30658/hmc.4.7

Fagone, J. (2021, July 23). The Jessica simulation: Love and loss in the age of A.I. San Francisco Chronicle. https://www.sfchronicle.com/projects/2021/jessica-simulation-artificial…

Knafo, D. (2015). Guys and dolls: Relational life in the technological era. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 25(4), 481-502. https://doi.org/10.1080/10481885.2015.1055174

Levy, D. (2007). Love and sex with robots. Harper Perennial.

Turing, A. M. (1950). Computing machinery and intelligence. Mind, 59(236), 433-460. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/lix.236.433