Bipolar Disorder

When Bipolar Disorder Moved Into the House

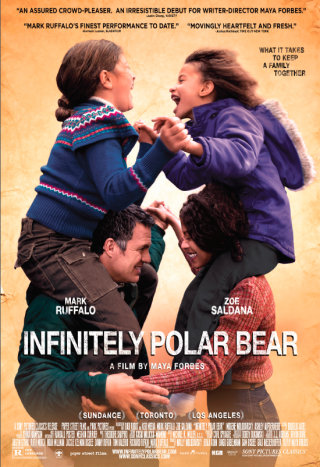

Writer/director Maya Forbes creates a moving portrait of love and chaos.

Posted June 24, 2015

Your film Infinitely Polar Bear, based on growing up with a bipolar father, played by Mark Ruffalo, has just opened. What spurred you to make this (wonderful) movie now, at this particular juncture in your life or the culture’s life?

I wanted to present a humane portrait of a person who suffers from bipolar disorder, but is a loving and loved member of a family. Having children caused me to reflect on my own childhood. I felt the culture today was telling me to be afraid of everything when it came to raising my kids. When my oldest daughter was little, some parenting expert said I should never lose my temper in front of her, because she might be scared. I tried this and I felt like a mommy robot. I wanted my children to see me as a full complicated human being, imperfect. That's how I had seen my own parents and it was painful to reckon with their imperfections, but also illuminating. And when you make mistakes you have the opportunity to apologize, which is a good thing to show kids too. I realized how much the hard, sad experiences I'd had as a child had benefited me.

Your family experience is portrayed with such warmth. Did it feel that warm in actuality? And I don’t mean every day—no one’s feels warm every minute of every day.

It was very warm. Both my parents told great bedtime stories, and my father was a terrific reader. I think reading to kids is so important. I felt very loved -- which was at times a burden, since I wanted my father to have something in his life other than me and my sister. Of course, there was also a fair amount of conflict and anger. But we all knew each other so well, no one was hiding who they were. We let it all hang out, the good and the bad -- I think that made it feel warm.

What scenes or experiences in the film were most different from your real life and why did you feel you had to fictionalize the experience?

To make a ninety minute movie, you have to fictionalize, condense, distill. It is different from writing a memoir. The film combines things that happened to me with stories from other people and some times I create all the elements of a scene to capture a true feeling that I felt. There are many important people who aren't in the film because it isn't a film about grandparents and aunts and uncles. There were way more broken-down cars, more schools, more everything. With a film you have to pick a story to focus on.

Mental illness is a “heavy” topic. Have you had any feedback from those who might think the very nuanced portrayal of someone afflicted understates the seriousness of it?

I wanted to tell the story of a period where my father was able to maintain his (relative) stability because he was not lonely, and he had responsibility. He also had two daughters who had to learn to take care of him as much as he took care of them. I never think his illness isn't serious. In fact at that time he was treated as a guinea pig -- he had many dangerous experiences with his medication. He loses his wife, and the film ends with the recognition that his children are going to leave him ultimately. That means he succeeded as a father -- he launched his girls -- but loneliness looms in the future. He is dealing with the serious consequences of his mood disorder. And why was my father able to hold it together during this time? That interested me. Mental illness is mysterious and doesn't present in one way, nor is there a single way to treat it. Finding what works is a process, a unique individual journey. I think there are a lot of wonderful people on that difficult journey, and I have empathy for them.

Among the many things that struck me about this film are two parallel themes. One, that there is much more humanity to the mentally ill than we might give them credit for. And two, children are often more resilient than we give them credit for. Were they conscious considerations as you wrote the script?

Yes, both those themes were very important to me and always present as I was writing.

I’ve come to think that all of us grow up in these little tribes called families, each of which has its strange set of customs. Yours had a particular brand of customs, but do you think it was really any stranger than what many others grow up with?

I have two families with two distinct sets of customs. My mother comes from an educated, middle-class black family. Her father was a doctor and her mother an educator. They had a recognizable outlook: get an education, work hard, bust barriers, help your community. She grew up well-off -- yet , among other indignities, she could not go to the ballet school her white friends went to, because she was black. This situation requires one set of lessons and coping strategies. On my father's side, the pressure to be effortlessly brilliant was crippling, because brilliance comes with sweat and failure. Money dribbled down from the top, but you weren't supposed to talk about money. All of this created an unhealthy culture of dependence. I am fascinated by these family tribes and their unique experiences and customs!

You and your sister obviously turned out to be highly accomplished individuals. What in your direct family experience do you attribute that to?

My parents encouraged us to express ourselves and there was a lot of room to just play and be creative. They also had high expectations of us. And my anxiety about not having money was a tremendous motivator, though not always healthy or fun to live with.

Your real-life daughter plays the young Maya Forbes, and you directed the film. One of the things that distinguishes this film is the believability of the child’s experience. What instructions did you give her about the feelings you had as a child.

I was often frustrated and often worried and I thought I was more powerful than I was. I gave both girls simple direction. I have two daughters, so when I wrote the script I had two opinionated little girls in front of me. That helped too. They can get really angry really fast.

And did this incredibly intimate exchange—your daughter playing you, you directing your daughter—affect the relationship between the two of you? It seems to me it could be a recipe for enormous empathy—or enormous disaster.

To prepare for some of the more emotional scenes, we would go off in a corner together and I would explain the context. I would cry, and that would make her cry, and then we would shoot the scene. So it was a recipe for empathy. The movie deals in part with a mother going off to pursue her career and what that means for the family. Making this film was hard on the whole family, but also exhilarating. My husband produced the film so he was quite busy too. I think it is inspiring for them to see their parents trying to do something meaningful together. I realized, as I got older, how much I appreciated my own mother's choices. I think it is okay for mothers to be ambitious. Another benefit of throwing yourself into something is: it gets you out of your children's business.

Did you write the script with Mark Ruffalo in mind to play your father? His performance seems inspired.

I didn't. I focused intently on the real people, knowing that the moment I cast the parts they would become something new. The moment I met Mark, I knew I wanted him to play the role.

And last, what question hasn’t been asked that you would like to answer?

Q: Where does 'Infinitely Polar Bear' come from? A: When my sister and I were in college, our father had a manic episode. We took him to McLean Hospital in Belmont. He was filling out the intake form and it said, "What is your diagnosis? Schizophrenia? Manic-Depression? Bi-Polar Disorder? Other?" He circled "Other" and wrote "Infinitely Polar Bear." He had been labeled for over thirty years, with labels that had negative connotations, and also labels that changed with the DSM. He wanted to come up with his own label for his condition; one that was a little bit silly, and positive, and expansive. That's how he felt sometimes.