Relationships

Is It Love, or Just a Scary Movie?

Experiments in misplaced arousal show how our feelings can go wrong.

Posted June 19, 2014 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Can you imagine watching a scary movie and then falling in love with the first attractive person you see as you leave the movie theater? Probably not. But classic social psychology experiments have shown that sometimes people do misattribute feelings of fear and anxiety to sexual attraction. More generally, researchers have found that when people feel physiologically aroused—racing heart, sweaty palms—they use environmental cues to help them determine why they are feeling that way (Schacter & Singer, 1962).

- Step 1. Notice I have sweaty palms and a racing heart.

- Step 2. Determine what is going on around me: Is there a big bear behind me? I must be afraid. Did I just get an award? I must be excited. And, in the case of sexual attraction: Am I on a date with someone I like? I must be really attracted to him or her.

Most of the time, this process should lead people to correctly figure out why they are feeling the way they do. However, as I mentioned above, there may be times when this process leads people to misattribute their physiological arousal to the wrong environmental cue, such as assuming you are really attracted to your date after you watch a scary movie together.

Do people really do this? To find out, Dutton and Aron (1974) conducted an experiment on two bridges, one scary, one less so. The fear-arousing bridge was a 450-foot suspension bridge made of wooden boards attached to wire cables. It hung 230 feet above rocks and shallow rapids, had very low handrails, and a tendency to tilt, sway, and wobble. The “control” bridge was made of solid wood; was wider and firmer than the first bridge; was only 10 feet above a small rivulet; had high handrails; and did not tilt or sway. The authors expected that people who crossed the suspension bridge would experience physiological arousal due to anxiety and fear, whereas people who crossed the control bridge would not.

How did they test this? On the far side of each bridge stood an experimenter who stopped males between the ages of 18 and 35 crossing the bridge without a female companion and asked them to complete a brief questionnaire. Afterward, the experimenter thanked the male subject and offered to explain the experiment in more detail later. Then the experimenter tore off a corner of the questionnaire, wrote down the subject's name and number and invited each subject to call if he wanted to talk further. Half of the male subjects met a male experimenter and half a female experimenter.

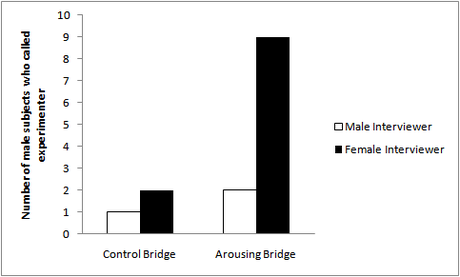

The big question: Dutton and Aron wanted to know how many of the male subjects would actually use the number to call the experimenter later. If people do misattribute physiological arousal to sexual attraction, then male subjects who crossed the scary suspension bridge and immediately interacted with an attractive female experimenter should be more likely to call her than male subjects who crossed a less scary bridge, or who interacted with a male experimenter. So what did they find?

Indeed, as the graph above shows, while only one or two male subjects who crossed the control bridge or interacted with a male experimenter made the follow up phone call, nine male subjects who’d crossed the arousing suspension bridge and interacted with the female experimenter gave her a call later on.

The bottom line? Perhaps, it's: Go on the roller coaster instead of the Ferris wheel, or pick the scary movie instead of the romantic comedy if you really want your date to like you. But more seriously, I think that this effect may play a small hand in phenomena like the Florence Nightingale effect and situations when a number of firemen left their wives for the widows of fallen comrades after 9/11. Of course, there are many other variables at play in these situations. Still, it may be best for us all to avoid making important romantic decisions on scary bridges or during crises, and if we really want to figure out our true feelings about our attraction to someone, we should probably avoid amusement parks on the first date.

Have you ever experienced a misattribution of arousal that led you to make decisions you later regretted?