Environment

Prison Art: Strings Are Attached

The tremendous drive to create in prison

Posted June 24, 2014

Not too long ago, I received an email from a long-time friend and colleague who was then a warden for a men’s prison. Known for her forward-thinking and support for programming and education, she has been a strong advocate for the arts in prisons.

She asked me if I wanted an art piece that was completed by one of her inmates. Could I use it for my classes? It seems that she had to confiscate it as contraband. Rather than destroy this beautiful piece, she sent it to me for safekeeping.

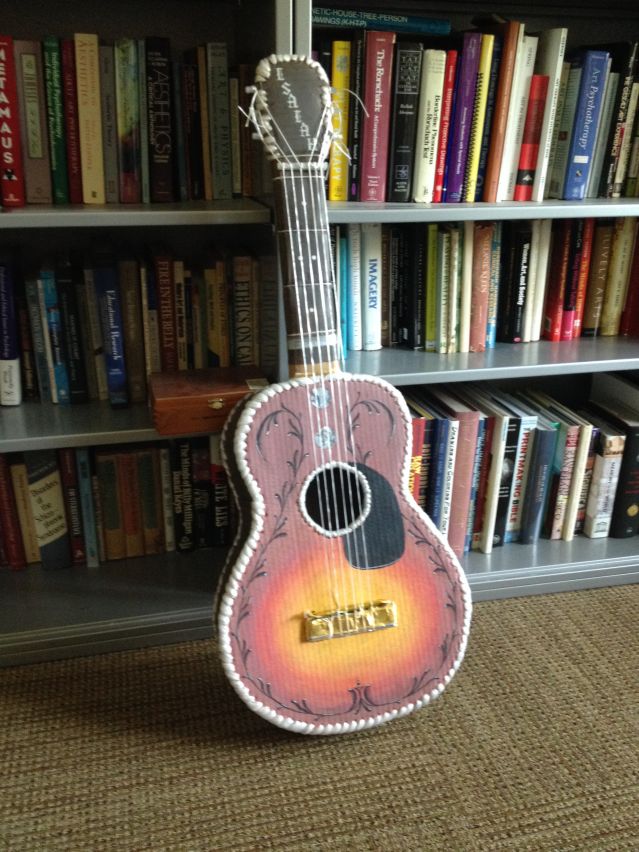

Here it is:

Guitar made out of found objects

It stands around 3 feet tall and is made from what some would call trash. It is constructed from cardboard, artfully folded and painted, sewn together with plastic garbage bags.

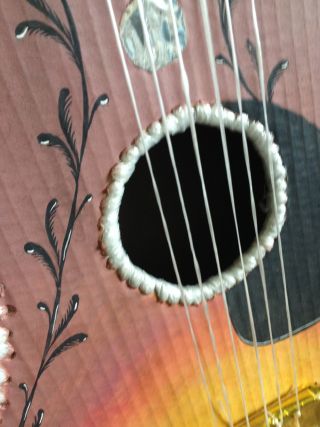

guitar-detail

The strings are stretched and twisted garbage bags, the tuning pegs are made from the plastic of disposable ink pens, and the saddle and bridge are made from candy bar wrappers.

guitar-detail

No information is provided on how it was painted, but the brown looks like show polish, and the black looks like pen ink.

guitar-detail

My colleague does not know from who it was taken—the only clue we have is the name on the guitar head, done in stylized white graffiti-like lettering. It is a common name. No way to tell whom it was.

Hence, we do not know what happened to him.

There was no art programming in this facility. This piece was constructed in the inmate’s free time, likely in secret. As a resident of this system, he knew it was contraband.

He didn’t make the piece for notoriety. We have no idea who he was, and I can’t imagine he showed it to many people. So what drove him to create?

In a previous post, Art Behind Bars, I wrote about the natural creative tendencies of those who are incarcerated. The last post, Drawing Alone: Making Art in Solitary Confinement, demonstrated how art making provided a sense of sanity, a refuge, for one placed in confinement. This piece, in all its tangible form, hammers home this drive to create “insider art.”

Kornfeld (1997), Ursprung (1997) and Rojcewicz (1997) all stressed that, as long as there has been incarceration, there has been art. Kornfeld reflects that the prisons are filled with creative energy needing to explode. As Urprung aptly described:

The incarceration experience, one of sensory deprivation, is a world of imposed controls, rigid regulations, tedium, minimum allowable risk, and consistent inconsistencies. It appears that the creative process (art-making) is an apt coping mechanism in order to survive such an oppressive dysfunctional milieu, especially to derive some sense of order out of chaos. (p. 17)

The piece was made for one reason—the need to make it.

As I was writing this, it conjured up a memory from long ago. This was in the mid-1990s, when I was an art therapist in a California prison. I was walking down the mainline to go to another wing when I saw an inmate carrying a rather large sailing ship, made entirely out of Popsicle sticks and paper. I stopped him so I could take a closer look.

It was one of the most intricate sculptures I had ever seen; no words could describe it. He was justifiably proud of it. He had spent many weeks working on it in the craft room during his free time and was transporting it back to his cell. When talking to him, he revealed he had no artistic training, and simply felt compelled to make it. His sense of accomplishment was palpable.

About a week later I saw him again, walking the mainline. I asked him about the sculpture. He told me in a matter-of-fact tone that a correctional officer confiscated and destroyed it as it was deemed contraband. He was fairly philosophical about it, shrugging in a matter that conveyed the idea, “What can you do? It's prison.”

I was furious for him—I felt impotent and frustrated. It wasn’t until much later that I realized that he must have known that it was only a matter of time before the piece was confiscated.

When all was said and done, it was the act of making it that was important to him. What happened to the piece after may have simply been incidental.

Sadly, my colleague has since left her facility, taking a position elsewhere. Prior to leaving, she sent me several other pieces that sit proudly on my shelf, awaiting me to fulfill my plan for a campus gallery exhibition of prison art.

I hope the inmate knows that his piece is safe and that my colleague knows how much I appreicate that she rescued this piece.

References

Kornfeld, P. (1997). Cellblock visions: Prison art in America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rojcewicz, S. (1997). No artist rants and raves when he creates: Creative art therapies and psychiatry in forensic settings. . In D. Gussak and E. Virshup (Eds.), Drawing Time: Art Therapy In Prisons and Other Correctional Settings (pp. 75-86).Chicago, IL: Magnolia Street Publishers.

Ursprung, W. (1997). Insider art: The creative ingenuity of the incarcerated artist. In D. Gussak and E. Virshup (Eds.), Drawing Time: Art Therapy In Prisons and Other Correctional Settings (pp. 13-24).Chicago, IL: Magnolia Street Publishers.