Law and Crime

The Art of Murder(ers)

Our fascination with the art of those that kill

Posted January 28, 2014

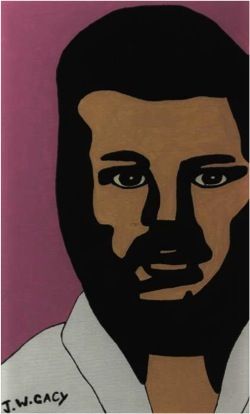

Gacy's self-portrait

At the end of last week, Dr. Scott Bonn posted on his Psychology Today blog Wicked Deeds, “The Strange Hobby of Collecting “Murderabilia”: Those who desire the artifacts of murder.” In this well written post, Bonn mentioned several valid reasons why collectors may be interested in purchasing artifacts of notorious serial killers.

Several years ago, I had the good fortune to be invited by Dr. Laura Henkel to her art gallery Sin City, in Las Vegas, to provide lectures on two separate occasions. The Arts Factory was selling some paintings by John Wayne Gacy, and Dr. Henkel wanted to provide an opportunity to explore their sociological and psychological impact through lectures and discussions. Although local professors refused to be attached to the event, the first series of lectures included noted criminologist Dr. Jack Levin of Northeastern University. The second series of lectures included the honorable Sam Amirante who, before he was a circuit judge, was one of Gacy’s defense attorneys.

Amidst a backdrop of Gacy’s original paintings and drawings, all of us reflected on different perspectives of a serial killer and his work (please refer to this article in the Las Vegas Review-Journal for local coverage of these lectures).

For years I had delivered art therapy services for many who were in prison for murder. Prior to the lectures in Las Vegas, I had provided expert witness testimony on the art of a man who murdered (details can be found in the Introductory post to this bloghere] and was finishing up the book that documented this experience [Art on Trial, published by Columbia University Press]. Now I was being asked to review and reflect on the paintings of a notorious serial killer.

Through these experiences, I was aware of an interesting dynamic. Oftentimes, I would show art pieces that would not otherwise earn a second glance. However, once someone is told the artist murdered someone, viewers linger over the piece with fascination and disgust. Such curiosity is reminiscent of rubbernecking—a perverse desire to gaze on the results of a horrendous act.

I learned that as much as we are attracted to the beautiful, we are fascinated by the ugly.

As one would expect, the Gacy art show and subsequent lectures were somewhat controversial, and garnered some interest and press. As a result, I took part in several interviews. One was by J. Boyett who interviewed me for the online magazine Sensitive Skin [this interview can be found here]. As expected, he asked:

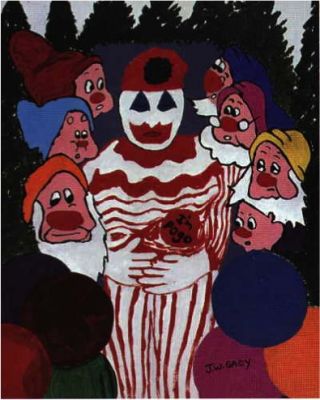

Gacy's clown with seven dwarves I understand the reasons for studying Gacy’s art. But can you speculate on some of the reasons for collecting it? What do you think are some of the motives for paying $15,000 for one of his paintings?

Gacy's clown with seven dwarves

I understand the reasons for studying Gacy’s art. But can you speculate on some of the reasons for collecting it? What do you think are some of the motives for paying $15,000 for one of his paintings?

This was, of course, the crux of the issue.

I indicated “that one thing I find fascinating… is that people may look at a piece of art work and say, ‘oh that’s nice', or 'well, I’ve seen better,’ but then they find out that it was completed by one who killed someone, and they are riveted. They look at the image with awe, with disgust, with undue attention… The art of murderers seems to attract less a systematic evaluation and more of a compulsive, macabre curiosity.”

During my interview with Boyett, I wondered aloud about why people find such work enticing:

“What are they looking for?

What messages do they hope to get from it?

Conversely,

Are they looking to find the morbidity within the art?

For the lack of humanity?

For the human element that exists in one who committed what was seemingly an inhumane act?

Some see the ability to create art as humanizing. Others may view the art as more of a warning that while we like to think there is a clear separation between the common, average person, and the infamous, callous, murderer, the art may reflect more of a bridge between these two types of people than we would like to realize.”

In the interview I also discussed the notion of our own Shadow, as described by Jung, the part of us that we stuff down and prevent from emerging because we are so afraid of it. I wondered if such work gives us an opportunity to glimpse and address our own fears, base elements and instincts, to give them an opportunity to be expressed.

“[Gacy’s work] is evidence of those whose Shadow reigned supreme, without control or balance, and it scares us. We can look at these pieces, and realize that as it was done by the hands of a human similar in make up to us…”

It is fair to point out that I found Gacy’s art mundane, sophomoric and primitive. I do know that Gacy was aware that others may pay top dollar for one of his pieces and was selling his own work to raise money for his appeal. I made the point during the lectures that unlike the defendant of the case that appeared in Art on Trial, this art did not reveal a mental illness; rather, if anything, it revealed the human detachment, the cynicism and sociopathy that existed simply because the images appear devoid of any emotional investment. Yet, we are still fascinated by it because Gacy did it. And it is still important for us to examine such art.

A painting by Charles Manson

Could our fascination with the art of murderers be an effort to grasp the glimmer of humanity the art may reveal? Or maybe it is simply intriguing to wonder how those who are so detached from humanity can be simultaneously destructive yet create works of art that resonate somehow—perhaps with the darker side within us all.