Depression

Mental Illness – Seeing and Hearing from the Inside Out

A photovoice exhibit on mental illness from the University of Calgary.

Posted May 22, 2018

Brad Necyk is a PhD candidate in Psychiatry and Fine Arts. He combines his skills in art with his life experience of bipolar disorder. Brad has curated a permanent photovoice exhibit at the Mathison Centre for Mental Health, Research, and Education in the Cumming School of Medicine at the University of Calgary entitled “Visualizing a Way Through.” The exhibit was opened this year during Mental Health Week (May 7-13). Andrew Bulloch, the Education Director of the Mathison Centre, assisted Brad Necyk in mounting the powerful display. The exhibit features 13 photographs and includes the artistic work of Necyk himself along with four other individuals who also share a life with mental illness. “Visualizing a Way Through,” as we are going to see, demonstrates the visual and audial experience of mental illness. I’ve chosen five images from the Mathison exhibit.

This is Kaj Korvela:

Kaj Korvela explains that his depression became so bad that he ceased to see in color. Everything was grey and black and white. This side effect of depression isn’t common, but it happens. One morning he woke and color had returned. He explains, in the script added to his photo, that he looked out and suddenly saw color on the breast of the robin. He hadn’t been able to do this for a long time. In his photograph the red and pink glass cubes on the roof of the building are like the robin’s breast. They’re a sign of hope and health. The remarkable reds filter out the grey of world beyond the cubes. But life, that grey world beyond the cubes, is still seen and inevitably filters through a medium that, though cheerful, only part blocks it out. Maybe this is what depression does. There is no direct unfiltered apprehension of the world about.

The text beside Kaj’s image reads like this: “I awoke one morning after being depressed for months on end seeing that a robin had landed on my balcony. I saw the color in the breast of the robin like it had been dipped into raspberry juice.”

And here is Mindy Tindall:

Mindy Tindall lives with depression. In her black-and-white piece we’re watching three people disembarking down a gangplank from an airplane. They’re at the end of their journey. Their faces can’t be seen. The passengers’ shoulders are hunched miserably against the wet and the cold. They don’t appear to be too thrilled at their wet experience. We watch them not directly but with our look filtered through a glass pane. The windowpane obscures what we can see because it’s covered in raindrops. They could as well be tears. It’s as if life can’t be seen directly because of the sadness. Life’s filtered through tearful glass. The theme, that viewing the world is something that happens through some sort of a screen, that it’s being filtered or even partly blocked, is important in Mindy Tindall’s photograph just as it was on Kaj Korvela’s rooftop.

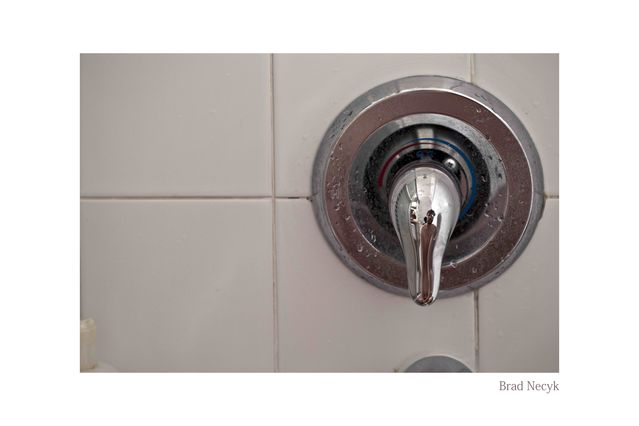

Brad Necyk follows:

Brad Necyk is the curator of the permanent exhibit from which these five photographs are taken. It’s bipolar disorder that he lives with. You have to look closely at Brad’s image to see what’s happening in it. That’s Brad reflected on the tap handle of the bathtub. His body is drawn out like an image in an Edvard Munch painting to match the shape of the handle. How we can see Brad and how he sees himself here is also filtered – it comes back from the reflective surface of the tap towards us as we watch. The tap has deliberately been placed off center in the image. What that tells doesn’t need too much emphasis. There are water drops on the surrounds of the tap. Teardrops again like those we saw on Mindy Tindall’s airport window? Brad Necyk explained that sometimes the bath is the only safe place in the world that he can find.

Lyne Bourassa is next:

Lyne Bourassa could be in bed. It’s sometimes a safe place for a person with depression. Lyne could be lying on her back and staring at the ceiling, just like Brad Necyk stands in the bathtub staring at that handle. But she’d have to tell us that her shot is taken on her back on her bed. Maybe it wasn’t. The fan’s motionless and purposeless. Is that how Lyne Bourassa feels in her bed or wherever it is she’s looking from? The globe in the fan’s off. There’s a glow of light on the left of the ceiling. It’s that fan that tells us about how she may feel. The fan’s off-centre in the image like the Necyk tap. Can we say that Lyne feels that her sighting of life is filtered through this image of an implement on the ceiling that’s going nowhere and is shedding no light?

And Collette Smith:

In this photograph by Collette Smith the filter is applied not to the eyes, but to the ears. The block can relate to language as well as to what’s seen. This is the theme of Collette Smith’s photograph. She copes with depression and PTSD. The problem that she’s alluding to is the uselessness of words and the refusal of many people to bother to listen to them. How can you link with a world where hearing’s obstructed and responses, based on a refusal to listen, are cutting? Words filter out and screen off real experience just as we saw sight filtered away in the first four photos. Here is the text that’s typed beside Collette Smith’s hand written comments:

“Cutting Words: The fact that I face stigma and discrimination on a regular basis is no secret. I learned this when I was about 12 years old hearing people talk about someone with an addiction problem and later when a cousin died by suicide. After I developed depression and PTSD, it shocked me to realize that while I heard cruel and ignorant things from members of the general public, the most cutting words came from members of the psychiatric community. All of the statements in this picture were spoken to me by psychiatrists that I have seen in hopes of trying to stabilize my illness and bring some stability to my life. The handwriting on the page is crude and rough, just like the words from those psychiatrists.”

The Mathison Centre has psychiatrists working in it. The criticism has been no impediment to the mounting of this image.

“Visualizing a Way Through” with its thirteen images from five different artists offers a unique perspective on the experience of mental illness. What’s most striking, despite the markedly different images, is the shared perspective they offer on the visual and audial feel of mental illness. Maybe this is one thing that depression does: it provides no direct, unfiltered understanding of the world around us. Viewing the world, hearing the world is something that happens through some sort of filtering or blocking screen. These are remarkable photographs. There is something exhilarating about seeing such unhappiness transformed into these five compelling images.