Environment

Why There's Hope for the Survival of Strong-Willed Beasts

Christopher Preston argues for the need for changes in attitudes about wildlife.

Posted February 23, 2023 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Preston writes, "Animals want to survive. They seek opportunities to exploit and new niches to occupy. They are tenacious beasts."

- He recognizes that news about wildlife is dire, stresses the importance of local psychology, and offers hope for ecological restoration.

- He draws on personal stories from researchers, Indigenous people, and activists who know the creatures best and offers a gripping narrative.

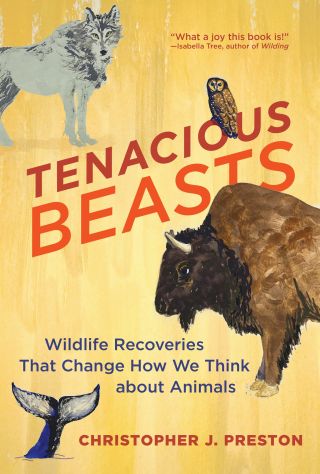

The minute I heard about University of Montana environmental philosopher and nature writer Christopher Preston's new book Tenacious Beasts: Wildlife Recoveries That Change How We Think about Animals, I knew I needed to read it and find out more about it from the writer himself.

It's widely known that countless species are dwindling in numbers or already have disappeared, and I was taken in by part of the book's description that reads, "Tenacious Beasts is quintessential nature writing for the Anthropocene, touching on different facets of ecological restoration from Indigenous knowledge to rewilding practices. More important, perhaps, the book offers a road map—and a measure of hope—for a future in which humans and animals can once again coexist."

Thanks to Christopher for taking the time to answer a few questions about his most important book.

Marc Bekoff: Why did you write Tenacious Beasts?

Christopher Preston: When COVID locked people in their homes in 2020, we saw emboldened wildlife walking over urban crosswalks, exploring Venetian canals, and nibbling the uncut grass of city parks. Housebound humans peered from their windows in surprise and delight. But people should not have been so surprised. Against the backdrop of extinction, a handful of species are recovering well. I wanted to shine a light on these anomalies. Profiling some of the successes provides a glimmer of hope in the midst of a biodiversity crisis.

MB: How does your book relate to your background and general areas of interest?

CP: I’m an environmental philosopher and a science journalist. I have spent the last decade fascinated by the technological transformations underway in “the Anthropocene.” In all the human attempts to re-engineer the planet, the biological world remains stubborn and resilient. Like P-22, the cougar who lived in Hollywood for a decade, wildlife keeps showing up. They wait in the wings for a chance to recover. Flip the script, examine the good news, and see what there is to learn. As a philosopher, you want the ideas you employ to be helpful. You also want them to be scientifically informed. I think the facts call for an update on how we think about animals.

MB: Who is your intended audience?

CP: This book is written for anyone who gets a thrill from wild animals. Whether it’s a vole nibbling discarded grass clippings or a blue whale sucking krill into its giant maw, most people are energized by the sight of wild animals. I also want to connect with wildlife managers, educators, and others who can influence the future of wildlife. Recovering species provide a unique opportunity to consider them with fresh eyes. Wolves, beavers, and sea otters, to name a few, are back. Society has changed in their absence, not least in the fact there are millions of advocates now ready to raise their voices on the animals’ behalf. Many of the old myths—e.g. the "big, bad wolf"—are being replaced. We should take this opportunity to learn better ways of being around animals.

MB: What are some of the topics you weave into your book, and what are some of your major messages?

CP: Humpback whale recovery in the North Pacific has been phenomenal. Their numbers are close to what they were before whaling. I joined a research vessel off Southeast Alaska with a marine mammal behavioral ecologist. She is studying how this resurgence of whales influences the carbon cycle. When you recognize the role of whales in carbon sequestration, it’s hard not to think of them as "allies" and "partners" in the climate change struggle. It’s an echo of how generations of coastal indigenous people thought about marine mammals.

Outside Canterbury in the U.K., I stared into the eyes of the first bison to live wild on British soil for 30,000 years. The matriarch had only been there for 48 hours! The bison ranger who walked me through the forest knew the bison would alter the woodland ecology. But he understood they would also impact the Iocal psychology. The U.K. has been missing its large, wild animals for centuries. The ranger told me young people in the region were thrilled.

Some animals need a lot of help to recover, at least initially. Others simply want to be left alone. Bobcats and elephant seals came back as soon as we stopped killing them. Imagine that! But bear advocates in Italy meticulously prune apple trees to produce fruit for recovering Marsican brown bears, and biologists in Washington have shot hundreds of barred owls to give spotted owls a chance. Sometimes we need to be heavily involved if recoveries are to spread.

MB: How does your book differ from others that are concerned with some of the same general topics?

CP: Many recent books about wildlife create feelings of despair. Think of Elizabeth Kolbert’s The Sixth Extinction or David Attenborough’s A Life on Our Planet. The outlook is bleak. I don’t deny that. But there is room for some measured hope. Having a vision of the possible is much more likely to generate results than focusing on the stream of depressing news. Talking about the tenacity of wildlife also feels more faithful to how the biological world operates. Animals want to survive. They seek opportunities to exploit and new niches to occupy. They are tenacious beasts.

I have learned a lot from books like George Monbiot’s Feral and Isabella Tree’s Wilding. But I’m not writing about turning landscapes wild again. I’m writing about the restoration and recovery of wildlife. Humans live on many of the same landscapes on which animals can return. Think of peregrine falcons that now dive from high rises to snatch pigeons from city plazas. In the Anthropocene, wildlife will not live very far from us. This is not about surrendering the land back to wildlife. It is about adopting more productive attitudes around how to share a planet.

MB: Are you hopeful that as people learn more about these amazing animals they will treat them and their homes with more respect and dignity?

CP: As a science journalist, I’m interested in startling facts. The people I met for this book are quirky and the animals are fascinating. I hope that readers seeking some positive wildlife news will be entertained.

But, between the lines, I’m trying to convey a message about better ways of relating to wildlife. I call it in the book’s introduction "a road map to a future state of mind." I’m hoping readers will come away feeling slightly displaced from their previous ways of thinking.

References

In conversation with Christopher Preston, writer, professor of philosophy, and one-time commercial fisherman who is obsessed with the sight of freshly falling snow. The most inflated title he ever possessed was Distinguished Visiting Fellow in the Ethics of the Anthropocene.