Relationships

What Happened After Human Carnivores Came to America

Dan Flores offers a riveting "Big History" of animal-human relationships.

Posted November 30, 2022 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- We can see humans not as a species apart but as a new animal entering a continent that had never seen mammals of our kind.

- Carnivorous humans had to adapt to environs that were already occupied by nonhumans and humans, who then had to try to adapt to their presence.

- 400 years of market-driven slaughter had devastating consequences for many ancient American species but many have made remarkable recoveries.

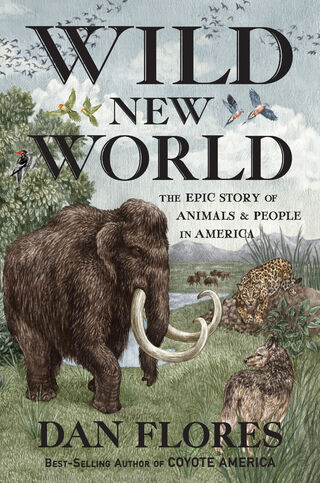

Award-winning author Dan Flores never ceases to amaze me with the seamless ways in which his eloquent writing blends facts and stories in a most readable way. His new book Wild New World: The Epic Story of Animals and People in America is another example in which Flores views humans not as “a species apart” but as a new animal—carnivorous hunters—having to adapt to new environs that were already occupied by nonhuman and human animals who had never seen mammals of our kind. Suffice it to say, all hell broke out.

Here’s what Flores had to say about his epic, highly original new book.

Why did you write Wild New World?

I’ve long been stunned that Americans remember so little about the marvelous biological diversity our continent once held or understand the realities of how we lost so much magic from the world. Most of us recall a kind of shorthand story that once there were millions of buffalo, then almost none. But who remembers that two centuries ago, Atlantic shorelines still harbored a northern hemisphere penguin, the great auk? That there was still an eastern prairie-chicken (the heath hen) until the early 1930s?

When my grandparents were alive, passenger pigeons—once the most numerous bird on Earth—still flew through our skies. As they had done for 5 million years, a century ago, wolves were still engineering our ecologies. America’s own parrot, the Carolina parakeet, continued to lend a tropical color to eastern forests only 90 years ago.

How does your book relate to your background and general areas of interest?

I was inspired by Jared Diamond’s books and by Yuval Harari’s Sapiens. The book is a historical and scientific narrative that covers a span from 66 million years ago to early 2022, so it’s what is known as a “Big History.” Despite that, I wanted to tell this story in a reader-friendly 400 pages or less.

Who is your intended audience?

Wild New World is written for the general reader who is intrigued by animals and who wants to understand the bigger story of humanity’s relationship with the world of nature. I strongly suspect that most readers won’t know much of the information and most of the stories in this book.

What are some of the topics you weave into your book, and what are some of your major messages?

A book that covers a span of time like this engages many topics, but among them is how America acquired its rich, distinctive bestiary and how an ancient world greeted the first human arrivals.

The book grapples with why America no longer has elephants. How a people who established our first coast-to-coast culture 13,000 years ago—Clovisia the Beautiful—forever transformed pristine ecologies. How and why, in the 10,000 years to follow, native people largely preserved biological diversity. How later naturalists—Mark Catesby, John James Audubon, Ernest Thompson-Seton, Vernon Bailey and Florence Merriam Bailey, Adolph and Olaus Murie, Aldo Leopold, Rachel Carson—unlocked the ancient secrets of America’s wild animals. Why, from the first, Americans were so committed to destroying the continent’s wolves. And how America’s market-based economies made possible 400 years of the most massive destruction of animals in world history, then pronounced that an act of civilization!

The Americas were the last continents on Earth humans found, and since we were repeatedly new to the place, First Contact Theory is part of my story. First Contact Theory assumes that beings can only respond to the new with the ideas already in their heads. In several forms—Biological First Contact, where animals with no prior experience with us had to learn to fear us, and Cultural First Contact, when Europeans and native people engaged in big conceptual misses about one another—Wild New World tracks this theme.

But I also write about “Continental First Contact,” where Americans across the last five centuries failed to appreciate the ancient ecologies they inherited. Acting on Old World traditions, we strove to remake America in the image of European nations that had long ago destroyed their own charismatic animals. Even when the U.S. created a system of vast public lands unlike anything Europe possessed, we’ve still struggled to imagine our way out of the blinders of Continental First Contact.1

Despite a history that can seem like an elegy, though, this is actually an optimistic book. Fifty years ago next year, at a time when saving the world was not political, we passed the Endangered Species Act of 1973, which remains today on the short list of America’s Very Best Ideas. Its successes are proof that nothing in history is truly inevitable and that we can find it in ourselves to change.

How does your book differ from others that are concerned with some of the same general topics?

In addition to being a narrative story based on up-to-date research, Wild New World has the advantage of the new genomic science to lay out its story, thus offering new information on the origins of American animals, as well (in several cases) as identifying the likely causes for their disappearance. Genomic science has fascinating new things to tell us about our long history as wild animals, too.

Are you hopeful that as people learn more about how we can truly and deeply connect with wild animals, we will come to treat animals and all of nature with more respect and dignity?

The evidence indicates that seeing a correct human relationship with other animals was never that difficult. From Neanderthals to the artists who created the astonishing art of godlike animals on the cave walls of Western Europe to native people in the Americas, many human cultures intuited an ancient kinship—we are animals, and animals are us.

But in the early U.S., where citizens believed animals should be sources of capitalist wealth, who believed extinction was impossible because a deity had made a perfect, unchanging world, cracking the dam of Old World certitude and seeing reality required a genius like Charles Darwin, whose blockbuster books finally revealed the great secrets of evolution, most importantly that like all the life around us, we, too, were the spawn of Earth’s evolutionary river. On the Origin of Species appeared a mere 163 years ago, though, and the inertia of human exceptionalism remains a powerful current.

But I do think that when readers get to the end of Wild New World, the book will have helped rearrange the furniture in their heads.

References

In conversation with Dan Flores, environmental writer and A. B. Hammond Professor Emeritus of Western History at the University of Montana. Dan has written for the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and the Chicago Tribune. His American Serengeti received the Stubbendieck Distinguished Book Prize in 2017. Coyote America is a New York Times Bestseller, winner of the Sigurd Olson Nature Writing Award, and was a 2017 Finalist for PEN America’s E. O. Wilson Prize in Literary Science Writing. For another interview with Dan, see "Coyote America: The Evolution of Human-Animal Relationships."

1) One last theme that tracks through the book: I argue that climate change is not the first time humanity has drastically altered our world. What we call the Sixth Extinction has different origins than we assume, in fact, has unspooled in slow motion across the last 25,000 years. A 2018 National Academy of Sciences study described the loss of 300 mammal species and two-and-a-half billion years of distinctive genetics as humans spread around the Earth as “close to a worst-case scenario.” Starting five centuries ago, species like passenger pigeons, which had been entirely healthy for 15 million years, proved unable to survive a mere four centuries as targets of market capitalism. Since 1,500 humans have taken out another half-million years of Earth’s evolved faunal genetics.

As Food Animals Became "Things," Their Feelings Were Ignored. (A new book explores how farm animals became objectified money-making products.)