Intelligence

"Are Chimps and Dogs More Sentient than Rats and Hamsters?"

This question from a middle-school student is essential, and the answer is "no."

Posted September 1, 2022 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- No evidence shows that mammals such as chimpanzees, wolves, dogs, and cats suffer more than other sentient animals.

- There aren't degrees of sentience. An individual's joy or pain is theirs alone, and speciesist comparisons are fraught with error.

- There are differences in how and what individuals feel within and between species.

- Research reveals that sentient reptiles experience mammalian emotions, and there are many other "surprises" about nonhumans' capacities to feel.

In an email a few weeks ago, 13-year-old Marta asked me,

Are chimps and dogs more sentient than rats and hamsters? Is my dog Harry more sentient than my hamster Millie? Do mammals suffer more than birds, fishes, and other vertebrates and invertebrates? I read your essay 'It’s Time To Stop Wondering if Animals Are Sentient–They Are' and you don't seem to think there are degrees of sentience.

Are there degrees or shades of sentience?

Sentience simply means the ability to feel. Marta also wrote,

I don't think Harry's joy or pain is greater than Millie's. I also don't think Harry is smarter than Millie and I don't think that an individual's intelligence makes a difference in how sentient they are.

I was duly impressed with Marta's views. I explained that "intelligence" needs to be considered in light of what an individual needs to do to be a card-carrying member of their species–it's an adaptation–and that comparisons among different species don't tell us much.

So, asking if a dog is smarter than a cat or a cat is smarter than a mouse isn't meaningful. Likewise, asking if dogs suffer more than mice ignores who these animals are and what they must do to survive and thrive in their own worlds, not in ours or the of other nonhumans.

All in all, what we know about the cognitive lives of other animals—how smart they are–doesn't lead to any meaningful claims that there are shades or sentience.

Every Individual Matters

When comparing different animals, we need to focus on individuals rather than on species. The treatment of other animals is often linked to how humans perceive their ability to think—to have beliefs and desires and to make plans and form expectations about the future.

An individual's joy or pain is their joy or pain. There are important moral implications of doing away with the notion that there are species-wide degrees of sentience and that intelligence is morally relevant. It could be argued that although some individuals' cognitive lives don't appear as rich as those of other "more cognitive" animals, the limited number of memories and expectations that "less cognitive" individuals have are each more important to them.

It's reasonable to ask: If some animals' memories are not so well developed so that they live in the present and cannot know about the passage of time into the future, do their pains have no foreseeable end, and do they suffer more?

For example, I might have known that my canid companion Jethro's pain might end in five seconds, but he doesn't know this. If his pains are interminable, then causing him the pain would be more serious than causing pain for someone to whom you could tell that it would only last for five seconds. But intentionally causing him pain might still be wrong even if he could know that it would only last for five seconds.

The moral importance of individuals also forms the basis for compassionate conservation and the science of animal well-being.

What does doing away with degrees of sentience mean?

To sum up, whatever connections between an individual's cognitive abilities and what treatments are permissible can be overridden by that individual's ability to feel pain and suffering. When we are uncertain, even slightly, about their ability to experience pain or to suffer, individual animals should be given the benefit of the doubt. While there is uncertainty about the phylogenetic distribution of pain and suffering, there is no doubt that individuals suffer.

The pains of supposedly "smarter" animals are not morally more significant than the pains of "dumber" animals. Solid science supports this view. Claiming lab rats, mice, and other animals are not animals as the United States Federal Animal Welfare Act does is absurd. In addition, rats and mice display empathy for the suffering of other rats and mice.1

Overcoming Cognitive, Emotional, and Moral Speciesism

There are numerous practical implications of viewing sentience on the individual level, including how we treat other animals—what's permissible and what's not—and debates about granting personhood to nonhumans.

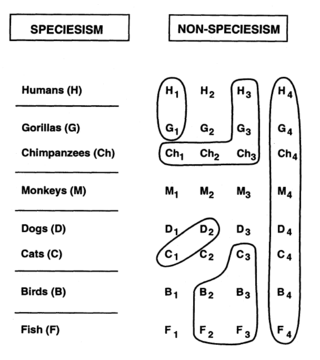

The idea that "higher" animals are more sentient than "lower animals" is speciesism. Speciesism informs decisions about how humans are permitted to treat other animals based on an individual's species membership rather than on that animal's unique characteristics.

Nonspeciesists, by contrast, use an individual's unique characteristics to make moral decisions about animal use and are concerned with how individual animals are viewed and treated. Differences between speciesism and non-speciesism are explained in Figure 1.2

Drawing lines in a hierarchical way is highly misleading. As the renowned philosopher Tom Regan once quipped, if you're going to draw moral lines to separate species, use a pencil. Philosopher Gary Varner rightly noted that we should make moral decisions with the evidence we have, not the evidence we wish or want.

It's time to stop drawing lines that portray misguided taxonomic hierarchies and purported degrees of sentience, do away with species-wide misleading generalizations about animal sentience, focus on what individuals are feeling, and expand the community of equals.

References

1) For more information on empathy in rats and mice click here.

2) Also consider James Rachels's notion of moral individualism that is based on the following argument (pp. 173-174), "If A is to be treated differently from B, the justification must be in terms of A's individual characteristics and B's individual characteristics. Treating them differently cannot be justified by pointing out that one or the other is a member of some preferred group, not even the 'group' of human beings." According to this view, careful attention must be paid to individual variations in behavior within species.

Bekoff, Marc. Resisting speciesism and expanding the community of equals. BioScience, 1999.

Deep Ethology, Animal Rights, and the Great Ape/Animal Project: Resisting Speciesism and Expanding the Community of Equals. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 10, 269–296, 1997.

It’s Time To Stop Wondering if Animals Are Sentient—They Are.

Assuming Chickens Suffer Less Than Pigs Is Idle Speciesism.

Sentient: How Animals Illuminate the Wonder of Our Senses.

The World According to Intelligent and Emotional Chickens.

Spain Joins Other Nations in Declaring Animals Are Sentient.

Should Sentient Insects Be Farmed for Food and Feed?

GUNDA: A New Film on Animal Sentience Recalibrates Morality.

Minding Animals and Sentience in the Old and New Worlds.

Compassionate Conservation, Sentience, and Personhood.

Animal Emotions, Animal Sentience, and Why They Matter.

Sentient Rats: Their Cognitive, Emotional, and Moral Lives.

The World According to Intelligent and Emotional Chickens.

A Tribute to Dr. Victoria Braithwaite and Sentient Fishes.

Sentient Reptiles Experience Mammalian Emotions.

Sentience and Conservation: Lessons from Southern Africa.

Sentience is Everywhere: Indeed, It's an Inconvenient Truth.

Animal Sentience is Not Science Fiction: Recent Literature.

The World According to Intelligent and Emotional Chickens.

The Animals' Agenda: An interview About Animal Well-Being.

Dogs Are Not Smarter Than Cats, and More: A Media Muddle.