Stress

Dogs Mirror Our Stress and We Know More About How and Why

Research shows that our cortisol levels are matched by our canine companions.

Posted June 8, 2019 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Just after I posted the essay, "'Bad Dog?' The Psychology of Using Positive Reinforcement," I received an email informing me of an essay published in The Guardian—"Dogs mirror stress levels of owners, researchers find." I found it extremely interesting for a number of reasons, including the fact that research has shown that dogs are very tuned into what we are feeling—they read our faces very well—and also that a recent study has shown that a person's emotional state and confidence play a huge role in getting them to use positive reinforcement training on reactive dogs. (See "Dogs Watch Us Carefully and Read Our Faces Very Well" and "Can Dogs Tell Us We're Angry When We Don't Know We Are?") It seems highly likely that the willingness to use positive training and its effectiveness on "difficult" dogs stems from the nature of the relationship that a dog and their human have formed. There are two sides to a dog-human relationship, and the people side should not be neglected.

The Guardian report is a summary of a research paper published in Scientific Reports by Ann-Sofie Sundman and her colleagues, in which 25 border collies and 33 Shetland sheepdogs were studied along with their female human companions. Both are available online. The Guardian piece begins, "In research that confirms what many owners will have worked out for themselves, scientists have found that the household pets are not oblivious to their owners’ anxieties, but mirror the amount of stress they feel." It turns out that dogs store cortisol in their hair, and each hair shaft essentially functions as a record of an individual's stress.

The research by Ann-Sofie Sundman and colleagues offered some very interesting trends about hair cortisol concentrations (HCC) in dogs and their humans. For example, they learned that the tight link between dog and human cortisol levels was higher during winter than in summer months, and the relationship between dog and human cortisol levels was greater in competition dogs than in non-competing canine companions. The researchers suggest that the second trend might be due to the development of a stronger bond between competing dogs and their humans, due to regular training for competitions. However, they also caution, "Of course, the difference between competing and pet dogs may not only be the lifestyle in itself, they may also differ in traits not covered within the scope of this study. Certain traits may make a dog more suitable for canine sports that may also affect the stress response."

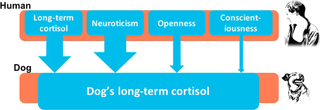

It also turns out that living conditions, the humans' working hours, and the presence of other dogs didn't influence cortisol levels. However, the humans' personality traits, including neuroticism, openness to experience, and conscientiousness, were found to influence long-term cortisol concentrations in dogs, with neuroticism playing the most significant role. Dogs who lived with humans high on a neuroticism scale tended to have lower cortisol levels. Lina Roth, one of the researchers, notes, "more neurotic owners may seek more comfort from their pets, and the onslaught of hugs and attention reduces cortisol in the dogs." It's also interesting that a dog's own personality didn't strongly influence their cortisol levels.

So, who's mirroring who? Based on their data, the researchers concluded, "Since the personality of the owners was significantly related to the HCC of their dogs, we suggest that it is the dogs that mirror the stress levels of their owners rather than the owners responding to the stress in their dogs."

In a previous essay, I chose a photo of a homeless man and his dog, because it jives with the results of this study, and also because it reminded me of a discussion I had about the close relationship between homeless people and their dogs in which a former homeless man said, "Dogs absorb empathy among the homeless. They reflect the emotions of the people around them, and they feel what I feel." (See "Among Homeless People, Dogs Eat First and 'Absorb Empathy.'")

When intuition meets data, interesting and important discussions follow

The results of this very interesting research project demonstrate for the first time the synchronization of stress levels between two different species. Given the long-term association between dogs and humans, the results of this study aren't all that surprising. Many people who have lived with dogs have intuited the synchronization of stress and other emotions between dogs and their humans. For them, this sort of cross-species empathy is rather common and to be expected. When I mentioned this research to a few people, one person said, "So, big deal, I already knew this," and another remarked, "Science needs to pay close attention to common sense. Anyone who's lived with a dog knows that they and their human companions reflect one another's feelings." My comment was simply, "Now we know more about the physiological basis for these shared feelings and that it's the dogs mirroring their humans, not vice versa."

When intuitions offered by citizen scientists and others who take the time to learn about the relationships they have with their dogs meet formal science, there can be a lot going on and often some very interesting, important, and useful discussions about how what we already "knew" matches with what science tells us. This is not to say that formal science always rules, but rather that it's essential to pay close attention to how common sense and science sense jive or don't jive with one another. Of course, it remains entirely possible that some highly controlled studies of a handful of dogs in a particular setting don't reflect what they really know or feel and ultimately have limited application to dogs in general. So, we also can learn a lot from this mismatch. (See Canine Confidential, Unleashing Your Dog, "Citizen Science as a New Tool in Dog Cognition Research," and references therein.) And, of course, we need to pay close attention to the behavior and personality of individual dogs, because there is no "universal dog and lumping them together is fraught with errors."

Where to from here? What about dogs who aren't "homed"?

To sum up, the current research project does indeed reflect the intuitions that many people have about shared emotions and empathy with their canine companions. It also provides a physiological basis for emotional contagion and synchronization. This study, similar to many such projects on dog behavior and dog-human interactions used "homed dogs," and it would be very interesting to conduct a similar study on more independent dogs, including free-ranging and even feral dogs who have little to no contact with humans. Of course, a dog's past experience with humans may play a role in how well they synchronize their emotions with humans, but we really don't have any details about this possibility. And it would be very interesting to know more details about why some "homed" dogs don't synchronize with their humans.

Clearly, in addition to valuable data, there's a lot of food for thought in Sundman and her colleagues' study, and I hope other researchers will follow these different leads. Stay tuned for further discussions of the ways in which dogs and humans exchange information on their emotional states. It will be interesting to see how well our intuitions match with scientific research, and even if they don't, we'll continue to learn more about the underlying bases of the social dynamics that develop between dogs and humans and these data will surely lead to further studies.

There's still much to learn about dogs and the various relationships they form with humans, and even if many people "already knew" this or that, it's a very exciting time to study dog behavior and the nature of dog-human interactions. The more we learn, the better it will be for dogs and humans—a win-win for all.