Trust

Inmates and Art: Connecting With Animals Helps Soften Them

When prisoners talk about animals, we learn a lot about their hopes and dreams.

Posted October 11, 2018

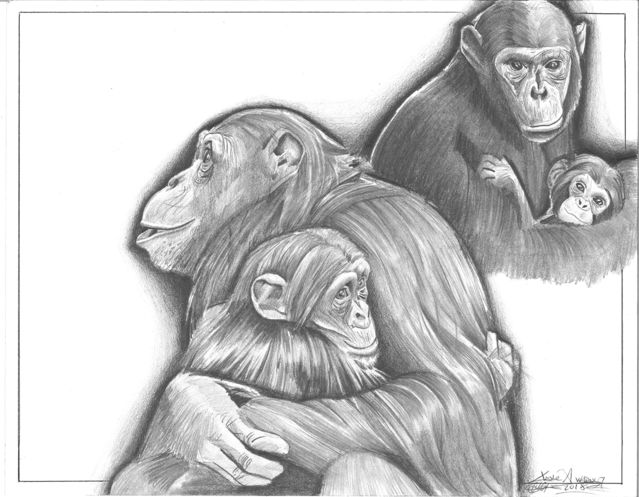

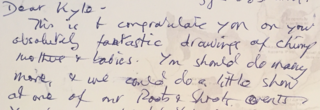

For 17 years I've been teaching a class that focuses on animal behavior and conservation in the transitions program at the Boulder County Jail in Colorado as part of Jane Goodall's global Roots & Shoots program (for more information, please see references below, in which there also is a lot more artwork). In October 2015, Dr. Goodall visited the class and thoroughly enjoyed herself. Needless to say, the students did too. Recently, in response to Kyle Warner's drawing of chimpanzee mothers and their children, she sent him a handwritten card, part of which is included here. Jane regularly sends personal notes when the guys reach out to her, and they treasure them and often share them with their children.

Here is an update to other essays I've written about this unique program based on some recent projects in which some of the students have produced award-winning artwork and prose, some in the form of letters and cards to Dr. Goodall.

Many of the men have lived with dogs, cats, gerbils, lizards, and snakes, and one guy told me how much he bonded with a fish as a child. For many, a dog was their best friend who, they told me, was able to read them better than people could. With all the issues about trust and being judged that these guys have experienced, many bond best with nonhuman animals (animals). Some talk about wanting to move to the country with a dog and enjoy nature when they get out. And, some have worked in different programs in various correctional facilities in Colorado and elsewhere in which they train dogs who are then adopted. A number of guys have worked with horses who have emotional problems to try to rehabilitate them while incarcerated. These sorts of experiences are known to have positive effects on inmates in terms of their connecting not only with other animals, but also with other humans. Often, when talking about these experiences, the word "soften" is used to explain how working with other animals has made them more compassionate toward other humans. (For more information I encourage readers to watch the documentary "Dogs On the Inside" and to visit websites for Puppies Behind Bars and similar programs and organizations.)

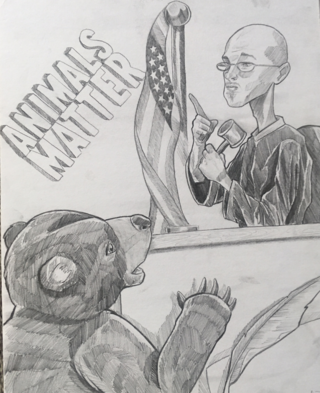

Recently we've been discussing compassionate conservation, a field in which one of the guiding principles is that the life of every individual matters. They truly and fully understand this at many different levels, including when they reflect on their own lives and those of family, friends, and those who they have harmed. Focusing on conservation and animal abuse, they've written letters to stop the trophy hunting of grizzly bears in the greater Yellowstone area, gotten involved in a campaign to bring wolves back to Colorado, and have sent supportive letters to Jill Robinson who founded Animals Asia, an organization that is working hard to stop bear bile farming in China. They're also appalled when wolves are killed as they have been in Washington state, and when coyotes and black bears are killed locally.

Many of my students are from rural areas in the United States and abroad, so they're sensitive to human encroachment on wild lands. They resent it when animals are cast out and labeled as the "problem" when it is clear that humans are the problem. And despite the things some have done to people, they get extremely angry about animal abuse.

Watching movies, including documentaries, also plays a large role in exposing the students to various aspects of animals' lives. They love talking about them afterward. Many say it softens them. These discussions give them the chance to talk about the importance of social relationships as well as compassion and empathy. They often find common ground among one another they didn't know existed. These discussions and debates connect them to others in the program and to the outside world including nature. I've had some of the most guys who committed serious crimes say that the class has had a strong positive effect on them. One said talking about dog behavior and dog-human relationships helped him realize that he needs to extend more compassion to humans. Researchers refer to dogs and other animals as "social catalysts" when they help people connect and reconnect in this way.

I recall at one of the first meetings years ago someone was talking out of turn as I was setting up the curriculum. One of the guys yelled, "Hey, shut up, you're acting like an ass. This guy's here to help us." I responded, "You’ve just paid him a compliment." Some were surprised so I explained that animals can be kind, compassionate, and empathic. While there's surely competition and aggression, there's also a lot of cooperation, compassion, and empathy. I explained that these behaviors are examples of "wild justice" and this idea made them rethink what it means to be an animal.

Over the years, we've often talked about how we should be proud to be animals and that we have so much to learn from them. In fact, that's one of the reasons why I wanted to teach the class and the jail administrators allowed me to do so when I first approached them. Most of the students have had enough of nature red in tooth and claw and many lament, "Look where that 'I'm behaving like an animal' excuse got me."

From time to time I ask the inmates what they get out of the class. Here are some responses:

--The course is healing.

--I've learned a lot about understanding and appreciating animals as individuals.

--The class balances scientific rigor with social consciousness.

--The class gives us a sense of connection to webs of life.

--What I do counts. I now have a vision for the future.

--The class models healthy prosocial ways of living and working in the world.

--The class makes me feel better about myself.

-- Marc’s message is simple: We should be proud to be animals, and we have so much to learn from the behavior of other animals.

Some of the notes they wrote on the card that Kyle Warner put together for Jane Goodall reflect these messages and more. Two thoughts that often come up is that other animals don't judge them and they trust them. This is huge for people in their position.

Let me focus on what Mr. Warner wrote on the card and in a letter to Jane. On the card he wrote,

"You do so much to restore my hope in humanity and hope for animals. I've always wanted to be part of something bigger than myself, and your [Roots & Shoots] program makes me believe that there could one day be a place for me somewhere that matters."

In his letter, he wrote a number of gems that reflect what others have also written over the years. For example, "I feel such empathy and warmth for chimpanzees...it's a love and curiosity that makes me feel so grateful for people like you, messengers of hope." He goes to write that when I arrive and the class begins "It's cool to see my peers let down their guards, remove their many masks that serve to defend them from the cruel world they've come to know. It's like when Marc arrives and we begin to talk about animals, I'm able to see everyone around me take the form of their inner child...we all display our innate ability as well as our desire to trust, and we all share this common ground of joy and childlike curiosity. That's a big deal in a place like this...my peers and I all pretty equally love animals and even trust them in stark contrast to humans."

All in all, science and humane education -- talking about what we know about the cognitive and emotional lives of animals -- have helped the inmates connect with values that they otherwise wouldn't have done. I'm pleased that I've had requests from different departments of correction in the United States and aboard about my class. And last May a crew from Netflix came and filmed the class as the guys talked about empathy for other animals and their dietary choices. Over the years, a number of students have "gone veggie" or vegan because of the class.

Learning about other animals and drawing them, writing about them, and interacting with them all open doors for stimulating understanding, trust, cooperation, community, and hope. It can keep their dreams alive. Importantly, the discussions and debates also allow the guys to learn how to harmoniously settle disagreements among themselves and with other people. I've been told this a number of times by some of them and a few of the guards.

There's a lot of food for thought here for conservation psychologists and anthrozoologists who study animal-human relationships. There's a large untapped population of individuals to whom animals mean a lot, but they haven't had the exposure needed to further their education or to express their feelings about these experiences.

After 17 years I continue to get as much out of the class as the students, and it's made me a better listener and teacher both when I'm with them and on the outside. I love talking with them about "all things animals" and can feel the enthusiasm and energy they bring to these conversations. Friday mornings, when I go to jail, are a very special time of the week for me. Many thanks to all of the students who have enriched my life.

References

Caitlin Rockett, Roots & Shoots: A unique program at Boulder County Jail has inmates learning from nature. Boulder Weekly, April 13, 2017.

Marc Bekoff. Animals and Inmates: Science Behind Bars. Psychology Today, September 23, 2009.

Marc Bekoff. Inmates, Animals, and Art: Creative Expressions of Hope. Psychology Today, December 17, 2016.

Jennifer Holland. Nature Behind Bars: Animal Class Helps Prisoners Find Compassion. National Geograpic, May 19, 2015.