Neuroscience

What It's Like to Be a Dog

New MRI research shows startling similarities in what lights up animals' brains.

Posted September 15, 2017

A few months ago, I was asked to write an endorsement for Dr. Gregory Berns' book, What It's Like to Be a Dog: And Other Adventures in Animal Neuroscience. I gladly said "yes" and was treated to a wonderful adventure into the minds and hearts of a wide variety of nonhuman animals. To conduct their studies, Berns and his team of researchers taught completely awake dogs to go voluntarily into an MRI scanner.

I was fascinated by what I read and reached out to see if he would answer a few questions. Our interview went as follows.

Why did you write What It's Like to Be a Dog?

My previous book, How Dogs Love Us, was the story of how my dog, Callie, and I got started with the crazy of idea of training dogs for MRI so we could figure out what they’re thinking. After that book was published, the project kept getting bigger and bigger. What started with two dogs grew to almost 100, and we began discovering things about how dogs’ minds work. So, much of my new book is about what we discovered. And not just about dogs — about other animals, too. (For another interview with Berns, please see "Dogs Are People, Too: They Love Us and Miss Us fMRI's Say.")

What are some of your major messages?

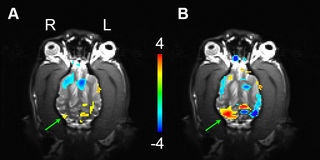

The overarching theme is that we see startling similarities in how animals’ brains function. This means that all animals — whether dog or human — have many neural processes in common. So when we see the same part of a dog’s brain active as a human’s under similar conditions, the implication is that the dog is experiencing something very similar to us. Also, just like humans, we see tremendous variation in these responses from one dog to another. This means that dogs, like humans, are individuals. We are quickly moving beyond the question of “what it’s like to be a dog” to “what it’s like to be that dog.”

Why do you think that non-invasive brain imaging is the wave of the future?

Because other animals can’t speak, we need a window into their minds to figure out what they’re thinking. MRI is great, because it doesn’t require any injections or radiation and is completely noninvasive. And by teaching dogs how to do it, they don’t need to be sedated or restrained.

You've been criticized by a few people who argue that fMRI research is not really non-invasive, that dogs suffer, and the data aren't really relevant to "the real world." How do you respond to this?

Because we don’t restrain the dogs, they are free to leave at any time. Sometimes they do. We have developed a try-out protocol to help us identify dogs that will actually enjoy the activity. Many of these dogs have done so many scan sessions that it is hard to keep them out of the MRI. I’ve seen dogs who are so eager to go in, they jump into the magnet even before we get the pet-steps placed in front of the table. I encourage people to watch the videos on various social media outlets and judge for themselves whether the dogs are having a good time. Is it the real world? Not entirely, but we try to design experiments that tap into cognitive processes that dogs employ in the real world and then follow up with simple behavioral tests outside of the scanner.

You weave some very important messages about ethics and research into your book. Can you tell us more about this line of thinking?

For many years, academics have tended to avoid the question of the subjective experience of a nonhuman animal, because it has generally been thought to be unanswerable. This has allowed scientists to sidestep the moral question of whether it is okay to use animals in medical research. When we see similar brain processes occurring in these animals, it becomes harder to ignore. And it isn’t just dogs: Every week, I read about discoveries on the sophisticated cognitive abilities of other animals. Certainly they aren’t automatons, like Descartes thought.

What are some of your future projects?

With dogs, currently we’re studying how they learn and how they process human speech. With other animals, I’m on a mission to build the Brain Ark, which is a digital archive of the brains of the megafauna before they disappear — hopefully to understand what they need to survive.

I found What It's Like to Be a Dog to be a fascinating read. It's packed with personal stories and lots of scientific data that clearly lay out just who these amazing beings are, from the inside out. I agree that it's essential to stress that there are large individual differences among dogs and other animals that need to be appreciated. There is no "the dog."

All in all, based on neuroimaging and other research, we can now learn what each individual animal wants and needs to have the best life possible in a human-centered world, and what we must do to make sure they do. Far too many of our companions don't get what they want and need from us. When we do all we can for our companions and other animals, it's a win-win for all.

Marc Bekoff’s latest books are Jasper’s Story: Saving Moon Bears (with Jill Robinson); Ignoring Nature No More: The Case for Compassionate Conservation; Why Dogs Hump and Bees Get Depressed: The Fascinating Science of Animal Intelligence, Emotions, Friendship, and Conservation; Rewilding Our Hearts: Building Pathways of Compassion and Coexistence; The Jane Effect: Celebrating Jane Goodall (edited with Dale Peterson); and The Animals’ Agenda: Freedom, Compassion, and Coexistence in the Human Age (with Jessica Pierce). Canine Confidential: Why Dogs Do What They Do will be published in early 2018. Learn more at marcbekoff.com.

Facebook image: Kangaru/Shutterstock