Alcoholism

What Is the Link Between Alcohol and Creative Genius?

My Pulitzer Prize winning grandfather believed he couldn't write without it

Posted October 5, 2016

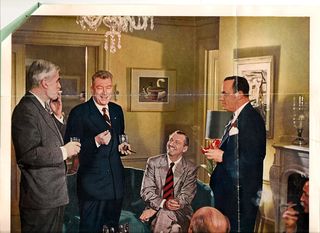

The year I was born, 1954, my grandfather, MacKinlay Kantor was on top of the world; about to publish a Civil War novel, Andersonville, that would perch atop the bestseller lists for nearly a year and win the 1956 Pulitzer Prize for literature. He was, in a phrase Tom Wolfe would coin thirty years later, Master of the Universe, and he looked it in a 1956 full page magazine ad featuring “Men of Distinction” for Lord Calvert Whiskey. Mack, as everyone called him, the titular Man of Distinction in this ad, looms the largest in the grouping of self-satisfied white men in a posh Manhattan hotel room. He is holding a pipe, and a whiskey glass of course—Lord Calvert, don't you know—holding the attention of all the other gents with what I can easily imagine is some ribald joke or personal story.

I came across the ad when I began to research his life for a book I was writing, almost 40 years after his death, by digging through thousands of documents in the personal papers he’d left to the Library of Congress. The image leapt out at me because it was evidence of just what a big deal he had been in his heyday, and bitterly ironic as well; by the time I was a teenager both his fame and his health had been eclipsed by an uncountable number of glasses filled with Lord Calvert and its competitors. I had always known that alcohol had led him to a slow and painful death—congestive heart failure is what it says on the death certificate. He died at 73 when I was 23, so I watched it happen. When I visited him for the last time in the hospital near his Sarasota, Florida home, he was insensible and had been speechless for a week. But when I came in his hospital room to see him tethered to machines and IV drips, he opened his eyes and uttered what in all likelihood were his final two words: ‘Horrible!” he said in a barely audible rasp. “Horrible!”

Aside from the fact of his alcoholism, I knew little about its origins or how he thought about it until I began to dig deep into his letters in those Library of Congress files. What I discovered broke my heart; the portrait of a man who believed alcohol fueled the creative energy it was ultimately destined to destroy.

The first sign of even an inkling of self-awareness by my grandfather that he had a drinking problem came in a letter written weeks after he had finished writing Andersonville, when he and my grandmother Irene, a painter herself, were on a supposedly recuperative trip to Europe and both sick as dogs: “I’m still coughing, still sneezing, still nose-blowing. I’ve taken the last desperate step, and am now On the Wagon—for how long I don’t know but certainly until I’m better. Perhaps that’s not literally true, but I mean no cocktails. . . . In Spain it would be almost impossible to go completely On.”

So he was aware, but unaware.

Both Mack and Irene had come from non-drinking families, and they’d learned to drink together as a release and a modest rebellion, staking out territory they saw as the proper ground of creative types. In his autobiography, Mack said he’d always felt alcohol was benign, even helpful, as a contrast to drugs of any kind, which he abhorred. “I had visions of becoming a groveling monster under the influence of drugs,” he wrote. “Liquor was something else. It was fun, it could be indulged in at the end of a hard day’s work if one had the price.”

Anyone who has watched the TV series Mad Men can easily picture the drinking culture Mack enthusiastically participated in as a rising writer with an overactive social life. No doubt, there had been embarrassing scenes and alcohol-fueled regrets aplenty during those years. But it took a persistent case of flu on the heels of the exhausting finish of Andersonville to make Mack think of taking that “last desperate step”—not even of stopping drinking, but just cutting back.

By then, according to the recollection of my uncle, Irene was already seriously concerned, as were their closest friends. If anyone said anything about it, Mack bellowed, “How the hell do you expect me to come down from that labor, this excitement, overnight?”

Being on the wagon, such as it was, clearly didn’t much outlast the sniffles. Back in the States, now a certified literary lion and for the first time in his life having the economic liberty not to immediately harness himself to another weighty writing project, he sloshed his way around the country.

My uncle described post-Andersonville visits to New York to see his editor and agent: “Always there would be drinks in their suite at the Algonquin, then cabs summoned, and then the grand procession to a table, with greetings from the manager or owner and a scurrying of waiters, and drinks and dinner and laughter, at this favorite restaurant or that. And at the end of the evening, he would insist on picking up the check for everyone, and tip quite grandly. . . He moved through some of those days in a bright alcoholic fog. Sober as a stern, demanding judge in the mornings; foolishly benign, foolishly angry, late at nights.”

I remember myself on those nights us kids were included in these excursions how, after his third or fourth cocktail, his face would seem to tilt sideways, his jaw shifting beneath slightly unfocused eyes as he brayed out a joke or a song; how he looked around for approbation, but more easily found something to irritate or enrage him.

At one big alcohol-fueled night out at a dinner theater performance, deep into the post-meal drinking, the emcee of the event announced to the crowd that the famous author MacKinlay Kantor was in attendance. A spotlight waggled its way around the tables searching, settling finally on Mack, passed out face down on his dinner plate.

The drinking had gone well beyond even the most liberal definition of moderation. I found a 1957 letter from Mack himself that paints the picture quite clearly:

“Made a nice acquaintance on the airplane . . . quite a drinker. We both were to have a little time in Dallas, so we killed a bottle of champagne in the bar, and then my flight got delayed . . . so we went back to the bar, more champagne. Our flight was called—engine trouble. Back to the bar. More Champagne. I think this went on two or three more times, but I can’t remember very well. . . . It took me two days to recover, but now I am drinking almost nothing, and feel grand.”

The key word in that last sentence: almost.

I can only imagine what Awful Incident made Mack grasp that his drinking had gone well beyond supplying the occasional amusing anecdote and was something that needed to be addressed. Was it a hideous public explosion? A bad fall? A near miss on the highway? All three in one night?

I’ll never know. But within months of the party in the Dallas airport bar, he wrote another letter, this one to a childhood friend: “I had a great deal of trouble with liquor ever since I saw you. When abroad usually I don’t drink too much, although there have been notable exceptions. Back in the US, with the pressure mounting on me from every angle, I found my only relaxation at the end of a day in about a thousand Gibsons, which of course necessitated further treatment next morning. So it went; I was on the wagon three different times, during one period of which I joined AA and was bored stiff with the people and their utterances, if not their practice. Finally I decided to seek divine guidance from the former head of the Yale Plan Clinic. He studied the thing from every angle—physical, chemical and psychological—and came up with the not too unexpected verdict that I could not drink like an ordinary human being, at least not at this moment in my life. The funny thing is that I find no difficulty ever in quitting. It’s just that I would prefer to drink and have liquor in my life. In the past I have gone a month on two different occasions, and nearly three months on another without trouble during the duration of dryness, but with the firmly-arrived-at intention of practicing moderation when I returned to drinking again. No soap—couldn’t be done. Thus I went dry on the 17th of Sept and will be dry until the 17th of March. My own hunch is that it will be like that from now on, punctuated with an occasional happy fling. . . .”

The problem, as Mack would put it exactly halfway through his time On the Wagon in another letter: “I’m having trouble re-establishing connections with my novel. I am far away from it just at present—intellectually I am eager to return to the fray; emotionally, I still recoil. This is a tough business in a creative existence—trying to adjust to a creative life without alcohol when it has determined one’s pattern of conduct for so long a time. However, I am willing to spend six months in trying.”

It happened that, during this brief dry spell, Mack’s friend Ernest Hemingway showed up with longtime companion and confidant Toby Bruce, who my grandfather described as their “mutual friend.”

“I told Ernest I was on the wagon for six months and couldn’t join them in a drink. Ernest looked at me sadly and said, ‘Mack, I have a crushed kidney, and you can’t drink with a crushed kidney.’ So I asked Toby what he’d have. He said, if the two biggest drunks in North America weren’t drinking then he wasn’t either.”

I found nothing directly calling his experiment with not drinking a failure, but I didn’t need to. Instead there was this, from early 1958, exactly two months before his dry period was supposed to end: “We talk about going to Mexico in the Spring; I am hoping to be working on my novel again. I certainly don’t feel like it now, or feel like much of anything else. This life of sobriety is not for me, but I must maintain it as scheduled until the 17th of March; then the hell with all such attempts.”

In April he wrote a long letter to the Yale alcoholism expert arguing the necessity of drink to his creative process. “The point I wish to make,” he wrote, “is that dreams of complication and clarity almost never occurred to me during the times when I was on the wagon. I am prone to regard these as evidences of a creative force and ambition.”

I think that was the end of his attempts to stop drinking for a number of years. In the summer of 1962, my Uncle Tim, then a freelance photographer, was in New York when he got a long-distance call from Mack: “I’m out here in [his hometown in Iowa] . . . . I’ve been drinking my way across the country—the booze had started to build up before I left Sarasota—and I’ve been drinking here, and last night they had a party for me. At six o’clock this morning I woke up and found that I was staring at the goddamn trees. I’d passed out on the lawn and so, I decided it was time to climb back on the wagon. The trouble is I’ve got the shakes, bad. I’m due in NY in a few days . . . but I don’t dare drive the car. I wondered if you could possibly fly out to Des Moines. . . . I can get the car that far.”

When Tim met Mack at the airport, he handed him the car keys, hands shaking. “I damn near didn’t get here, even though I only went at thirty miles an hour all the way,” he said.

Tim started out cross-country, his father, diminished, beside him. When they stopped for dinner, Tim hesitated before ordering a drink. Mack said: “Go ahead, you earned it. The booze is my problem, not yours.”

Another terrible irony: Alcoholism would eventually kill them both; Mack in 1977 and Tim twenty years after that.

Which brings me to . . . me.

Both my mother and my father drank all their adult lives. Based on what is now known about how alcohol impacts physiological health, they undoubtedly drank too much. They may have been partially psychologically dependent, with negative emotional consequences. I’m not talking falling-down, getting-the-shakes, tragedy-level consequences. It was more things said and done that couldn’t be unsaid and undone. By some definitions, any negative consequences of frequent alcohol use qualify as alcoholism.

According Robert Morse, MD, the former director of Addictive Disorders Services at the Mayo Clinic (and a million other sources), “the single most reliable indicator for risk of future alcohol or drug dependence is family history. Research has shown conclusively that family history of alcoholism or drug addiction is in part genetic.”

The relationship between individual genes and alcoholism is intensely complex and far from completely understood. Research with mice, though, has demonstrated one fascinating genetic link. Deficiency in a specific gene has been shown to increase anxiety behavior of mice in a maze, and those mice with increased anxiety go for alcohol over water when given a choice, while mice with sufficient quantities of that gene prefer water. In fact, when the gene-deficient mice drink alcohol, their anxious behavior diminishes—so drinking is an apparent attempt at self-medication.

Even if there is a human equivalent gene or combination of genes that could create a higher risk of alcoholism, not all offspring of parents with those genes would be at risk. Inheritance is always a roll of two dice, and it’s the combination that ultimately matters.

Ironically, my own genetic predisposition—or lack of it—would colorfully express itself one night when I was fifteen, and ironically on the beach behind my grandfather’s house. Mack had said a friend and I could camp overnight. He came by at dusk, as he almost always did when I camped there, and chatted for a bit, then left us to our own teenage devices. When we were digging a fire pit, we hit on a long buried six pack of beer – still full and unopened. I eagerly brushed off the sand on one of the cans, popped the tab, and took a big swig . . . then gagged and spit. God knows how long that six-pack had been buried, but based on the degree of flatness and staleness of the liquid it contained, I would have guessed Late Jurassic.

I grabbed the can out of my friend’s hand as he began to tilt it toward his mouth. “Don’t do it!” I shouted. “It’s completely foul.”

We settled for shaking the cans and spraying them on each other. I thought nothing more of the incident until many years later when my friend, who I hadn’t seen for some time, was telling me about his terrible descent into, and struggle to recover from, alcoholism.

“In fact,” he said, “I first glimpsed that I might have a problem with alcohol because of you.”

I told him I had no idea what he meant.

“It was that night we were camping at Mack’s beach and we found the six-pack.”

What about it, I said.

“Well you took one sip and spit it out, and then started pouring all the cans out on the ground, and the whole time I was thinking, ‘Wait a second! It’s still alcohol!’ The taste of it, which is what mattered to you, was completely irrelevant to me. The only thing I cared about was the buzz.”

For whatever reason, in the genetic crap shoot, I had apparently missed the gene or genes that would have led me to the same place my grandfather ended up, that place that could only be described by two words that were really just one word.

Adapted from the new book, THE MOST FAMOUS WRITER WHO EVER LIVED, by Tom Shroder