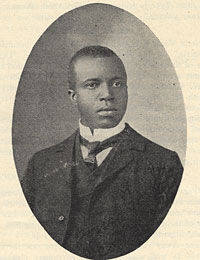

April 1, 2017 marks the anniversary of the death, 100 years ago, of the sublimely gifted American composer Scott Joplin. Classical radio and concert producers are dutifully noting the occasion, as they will do next year on the 150th anniversary of his birth. Accidents of the calendar make up the least interesting information when it comes to music programming, and yet it often seems like the only thing that people know how to talk about. These missed opportunities are dispiriting because they highlight how little our contemporary culture connects art music with everyday life.

The reason anyone knows Joplin’s music today is because of the 1973 film The Sting starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford. Although the story is set in 1936, Marvin Hamlisch made the inspired choice to score the film anachronistically. Ragtime had been a worldwide sensation at the turn of the 20th century—Joplin’s 1899 “Maple Leaf Rag” was the first piece of sheet music to sell a million copies—but as the United States entered World War I, ragtime died with its creator and was eclipsed by the Tin Pan Alley songs of Irving Berlin. By the 1930s, ragtime was long forgotten. Nevertheless, Hamlisch made the smart artistic choice of considering the emotional truth of the music over historical inaccuracy, and in so doing he helped bring Joplin’s music back from the dead.

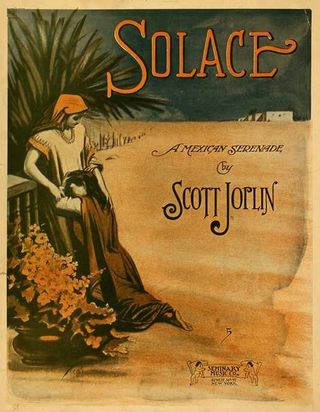

Thanks to the movie, Joplin’s rag “The Entertainer” became an international hit. (In the decades since, the melody has made its presence known to the world rather annoyingly an ice cream truck jingle.) For some reason, when the movie was first released I was drawn more to Joplin’s elegiac serenade “Solace.” Perhaps because I saw the film at an impressionable age, this piece of music imprinted itself on me, and I established a life-long connection to it.

The ability to form a deep, personal relationship to music is one of the qualities that draws us to listen in the first place. “Solace” is, for me, my go-to choice when I am looking for the feeling that the title promises. If I am especially vulnerable, listening to the piece can bring me to tears. Of course, others will hear it quite differently. The piece is quite sad, which is not everyone’s cup of tea, and indeed some psychologists worry that listening to sad music might cause people to ruminate and become sadder.

But it seems that’s not how it works. The growing field of music psychology research is sharing counterintuitive insights into the ways humans use music to regulate mood. One paradox is that the emotions we perceive in music are not necessarily the same as the emotions we feel within ourselves. This is why listening to sad music can make people feel happy.

Over the years, a music psychology lab in Finland has overturned commonly held beliefs about musical behaviors. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to scan the brains of men and women as they used music to self-regulate their mood, the researchers concluded that using music as a release—a strategy they identify as Discharge—is potentially maladaptive. One of the healthier strategies is what they call Diversion. This term describes those times when we use music to replace a negative feeling with something more positive. Another adaptive strategy they have identified is the use of music to find comfort by feeling empathy with another person’s pain. And the term they use to define this strategy is Solace.