A Tale of Two Sisters

As a gymnast born without legs, Jen Bricker grew up idolizing Olympic gold-medalist Dominique Moceanu from afar. Her discovery that they are long-lost siblings shines light on the complicated interplay of genes and environment in the creation of athletic prowess.

By Nancy L. Segal Ph.D. published November 3, 2015 - last reviewed on June 10, 2016

The “Magnificent Seven” members of the U.S. women’s gymnastics team captivated the world at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, earning the country its first-ever all-around team gold medal. The youngest member of the team, 14-year-old Dominique Moceanu, had also been the country’s youngest-ever all-around individual national champion a year earlier. By the end of the Games, she was idolized by thousands of aspiring young gymnasts—and, as she would later discover, one little girl in particular.

Moceanu’s life took several turns after her gold-medal performance: In 1998, at 17, she sued for emancipation from her parents, Romanian natives and former gymnasts who she claimed had squandered her earnings and been overly controlling, especially her father. In 2006, she married Michael Canales, a podiatric surgeon who had been a varsity gymnast at Ohio State. One night in their home near Cleveland, as the couple watched a TV program about reunited sisters, she casually asked him, “What if that happened to me?”

And then it did.

On December 10, 2007, Moceanu, then a nine-months-pregnant college student,

drove through the rain to her local post office to claim a certified envelope. She had missed its initial delivery attempt because she had been consumed with studying for finals. But it aroused her interest because fans typically sent letters and packages to her gym, not to her home address, which she tried to keep private.

Moceanu carried the envelope to her car, parked near a Walmart. The handwriting on it, she recalls, was “bubbly and unfamiliar.” Ripping it open, she found a typed letter of introduction, copies of adoption documents, and several photographs. Shocked by the uncanny resemblance between the young woman in the photos and her younger sister, Christina, Dominique thought the package might have come from a fan who happened to resemble her sibling. The thought that Christina and this person were identical twins reared apart flashed briefly in her mind, as did the thought that perhaps her father, Dumitru, had had a child out of wedlock. But then she took a closer look at the adoption papers and saw both her parents’ signatures. Turning back to the letter, she suddenly realized what had happened—what her family had kept hidden for so many years—and began to cry. The letter was from a younger sister, Jennifer Bricker, who had been relinquished at birth.

After confirming the story with her parents, Dominique called Christina, then a freshman at Sam Houston University in Texas. “Sit down,” Dominique told her. “We have another sister.” Christina was shaken, so Dominique repeated herself, then emailed her a picture of Jen at a homecoming dance so she could see the resemblance. “If I had shown the picture to my friends they would have thought it was me,” Christina says.

Jen, born six years and a day after Dominique, had been immediately placed in foster care by their father because she had no legs. Their mother, Camelia, never saw the baby. The decision to give Jen away reflected her father’s traditional cultural perspective that regarded physically challenged children with shame. Also, the family’s limited resources were dedicated to Dominique’s burgeoning gymnastics career. In her 2012 book, Off Balance, Dominique quoted her father, who died in 2008, as having told her, “We could barely take care of ourselves and you.”

But with the support of her adoptive family, Jen, in spite of her physical challenges, grew to become a champion athlete herself. By age 12 she was excelling in power tumbling—an acrobatic sport that combines artistic gymnastics and trampoline. She failed to understand why people singled out her achievements over those of her teammates. In 1998, she placed fourth in the all-around event at the Junior Olympics, the first physically challenged tumbler to finish so high. Her gymnastics idol growing up? Dominique Moceanu.

The sisters’ reunion makes for an inspiring story of family ties broken and restored. But it also provides priceless material for research into the roles of nature and nurture in athletic prowess.

Uncanny Connections

I have studied separated twins for many years, first from 1982 to 1991 as an investigator with the Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart (MISTRA). Today, I follow the progress of 16 young Chinese reared-apart twin pairs, as well as older twins separated due to unusual life events. I have seen striking examples of identical, reared-apart twins whose athletic talents coincided prior to any contact between them. Japanese-born twins Steve and Tom, raised by different families in the United States, both became competitive lifters and owners of bodybuilding gyms; Steve competed in the 1980 Olympics. Adriana and Tamara, born in Mexico and raised in New York, attended different Long Island colleges and found each other only after one was mistaken for the other. But both were already accomplished dancers and later performed together. Mark and Jerry, each six-foot-four, were both already volunteer firefighters when they met in their early thirties, each having developed the strength, stamina, and motivation to pursue the demanding role.

Studying twins, particularly separated-at-birth pairs, and separately reared non-twin siblings, is the best way to disentangle the genetic and environmental influences on individual similarities and differences. For example, such research could help determine if nature or nurture is the stronger factor in sports participation and achievement. But other physical actions and routines appear to have a genetic basis as well. Most reared-apart identical twins in the MISTRA group, for example, positioned their bodies the same way while standing for unposed photographs, which occurred less often among fraternal reared-apart pairs.

FOUND: ONE SISTER: Before their first call, Dominique (rear) worried about awkward silences with Jen, so she surrounded herself with notes. She wouldn't need them: They spoke easily for hours. Photo by Sasha Maslov

Genetically, Dominique, Jen, and Christina are as alike as fraternal twins. As for the origins of and links between their athletic skills, that’s an ongoing debate among researchers, parents, and coaches hoping to gain insight into how to identify promising athletes and guide them toward successful careers. Some attribute intragenerational similarities to the opportunities and encouragement parents give their children. However, athletically talented parents provide children with both genes and an environment in which to succeed (or not).

When siblings, like Christina and Dominique, are raised together, genes and experience cannot be separated. Growing up, Christina idolized her sister and was an aspiring gymnast for several years, a self-described “gym rat” who never wanted to leave the floor. But when her father sold his family-run gym in Houston, she left the sport, having no interest in training elsewhere. Christina is not shy about her talent and believes she could have pursued gymnastics in college or beyond. Instead, she turned to volleyball—and earned a college scholarship.

Did Christina follow Dominique into gymnastics because of her sister’s influence or because of their shared genes? When sister pairs share genes and opportunities, it is impossible to tell. Comparing separated siblings like Jen and Dominique tells us more.

Separate Childhoods

Dominique was 6 when her mother was pregnant with Jen, and recalls only that Camelia gained weight and stayed heavy for a long time. (Christina and Jen are just 22 months apart.) But at the time, Dominique’s life was already consumed by gymnastics, and her parents were private people. “Finding Jen has changed these memories,” Dominique says.

Dumitru never consulted his wife about his decision to put Jen up for adoption and arranged the baby’s placement on his own, Dominique says. She insists that Camelia, who is still alive, should not feel guilty. In what the Moceanus believed would be a closed adoption with no identifying information on the paperwork, Sharon and Gerald Bricker of Hardinville, Illinois, took custody of Jen when she was 3 months old. But somehow, the Moceanus’ names remained on the adoption papers. Later, when 9-year-old Jen and her family watched the 1995 U.S. national gymnastics championships and the camera panned over to Dumitru and Camelia, identified as the parents of the eventual champion, their name rang a bell for Sharon. Checking the adoption papers, she found the match. Their daughter’s connection to the Moceanus was indisputable, but the Brickers waited until Jen was 16 before telling her.

By then, their daughter was winning acclaim as a power tumbler, acrobat, and aerialist. She had been athletic from a young age, climbing trees, jumping on trampolines, and performing handstands. “I just came out an athlete,” Jen told me when I met all three sisters in Van Nuys, California, in June. “I was a little monkey.” The Brickers believed Jen could do anything she chose.

As a gymnast, Jen identified with Dominique and talked about her incessantly. In her letter to Dominique, she wrote, “Ever since I was about 6 years old, I’ve been obsessed with gymnastics, and I always watched you on TV. You had been my idol my whole life.” When she learned the truth about their connection, she says, “It was like watching a movie, only I was in it.”

A Genetic Kickstart

The logic of twin studies is simple yet elegant: Identical twins share all their genes, since they are formed from the division of a single fertilized egg. Fraternal twins result from the separate fertilization of two eggs by two sperm. Like ordinary siblings, they share 50 percent of their genes, on average. The greater similarity shared by identical twins demonstrates genetic influence and has been found to hold true for virtually all measured traits.

Researchers, including me, study identical and fraternal twins who have been apart since birth and do not meet until adulthood. Members of these pairs, who share genes but not environments, are especially valuable in psychological studies—they provide direct estimates of genetic effects, while reared-apart fraternal twins provide a critical comparison group. Reared-apart non-twin siblings like Jen and her sisters are also informative, although their age difference can make them somewhat less alike than fraternal twins.

Studies of adoptive families—parents, children and sibling pairs who live together but do not share genes—can tell us how much shared environments underlie behavioral similarities.

Behavioral genetics also values twin and adoption studies. At the crossroads of psychology and genetics, it aims to untangle the genetic and environmental factors that explain similarities and differences in intelligence or personality. DNA connections define Dominique and her sisters’ sororal ties, underpinning family traits that they all share to various degrees.

There have, however, been few specific studies of sports skill within families with pairs of unrelated siblings reared in the same home. Jen’s three older brothers, for example, played recreational baseball and basketball, but none was as successful as she was in her chosen sport.

A 2005 twin study by Dutch researcher Janine Stubbe showed that genetic effects on sports participation increase after adolescence, as children gain the freedom to enter and create environments compatible with their genetic proclivities. Her subsequent 2006 study confirmed this finding, and numerous twin studies from around the world have found similar genetic effects on oxygen uptake, anaerobic capacity and power, cardiac mass, and other performance-related fitness characteristics.

Claude Bouchard of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, is one of the few researchers to combine twins and adoptees in genetic studies of sports-related traits. His 1984 study of submaximal physical working capacity—an index of aerobic metabolism and oxygen transport that boosts muscular activity and endurance—found the greatest resemblance between identical twins, followed by fraternal twins, biological siblings, and adoptive siblings and showed strong genetic influence on these traits. These findings have serious implications for how we make the most of our physical abilities and overcome our limitations.

Seeking Dominique

It’s not easy to contact famous people. Jen had hoped to have an usher forward a note to Dominique when her older sister performed in a gymnastics exhibition in Illinois, but that event was cancelled. Jen also joined a Dominique Moceanu fan club, but it offered no direct routes to the gymnast. “I would look at her website and see pictures of two sisters,” Jen says. “But I knew there were three.” Jen’s family eventually found a way to reach Dumitru by telephone, and while he did not deny Jen’s identity, his concern over potential exploitation of the family’s famous name made him cautious and defensive. (Dominique later said that he never wanted to meet the daughter he gave away.) Finally, Jen imposed upon her uncle, a retired private investigator, to locate Dominique’s address. He did, and soon after, she delivered her carefully prepared package to the post office, grilling a postal clerk to be certain that no one could possibly sign for it except Dominique.

“Discovering a sister was the most shocking experience of my life,” Dominique says. “Nothing prepares you for this. But I knew that how I approached the situation would set the pattern for the future, and I wanted Jen to know that she would be accepted. I wrote her a letter telling her that—and that she would be an aunt.”

Dominique does not like putting things off, but the birth of her daughter, Carmen, on Christmas Day, 2007, delayed her first call to Jen until January 14, 2008. Fearful of awkward silences in their conversation, she surrounded herself with Post-it notes on which she had written questions she might forget to ask and information she might forget to share. Finally, she dialed, said, “Hi, it’s Dominique,” and heard Jen shout, “Oh, my God!”

They spoke for hours—Dominique never needed her Post-its. During the call, she learned that Jen had been born without legs. Her father had mentioned it when they discussed Jen, but Dominique thought Dumitru might have been exaggerating, especially since Jen had written about competing in gymnastics and playing volleyball.

Later, when Christina and Jen connected by phone for the first time, Christina says, the experience was “supernatural.” The three sisters finally met in person in Cleveland in May 2008—Dominique greeted Jen with a rose, as have newly reunited twins I have known. The trio bonded immediately, their similar mannerisms and gestures reinforcing family ties. Dominique describes the meeting as “surreal, yet stingingly real.”

The sisters have since become close friends and confidantes. When she first met Jen, Christina says, “It felt as if we were picking up where we left off. We had five days together, and it felt so natural. We never ran out of things to say.”

When I met the sisters in Van Nuys, I learned that all three have butterfly tattoos—each acquired independently, with Jen’s and Christina’s in the same spot, on their lower right back. (No study has been conducted, but I suspect the preference for permanent body decoration has at least a partial genetic basis.) During a December 2009 visit, Dominique, Jen, and Christina decided that they wanted new, matching “sister tattoos.” They chose a whimsical swirl with three twinkling stars.

“We are making memories,” Dominique says.

Moceanu DNA

The three sisters’ perceptions of one another’s behaviors confirm their genetic connection: All three display a childlike glee when describing their similarities, which well outnumber their differences. Their experience fits with findings that genetic factors explain 50 percent of individual differences (and similarities) in most personality traits.

Dominique and Jen are both extroverted, driven, and competitive. They are also perfectionists and “performance hams” who love being in front of a crowd. Their voices sound the same, whether speaking or laughing, and they use their hands a lot in conversation. Jen recognizes traits in Dominique that she sees in herself, such as leadership and initiative. Both are tough, detail-oriented, and able to push themselves emotionally and physically, perhaps explaining their commitment to the long hours and personal sacrifices required for success in gymnastics.

According to Dominique, though, an important difference between them is that Jen has “super-high confidence, whereas we were beaten down by our father. I walked on eggshells.” Jen herself credits her competitive success and self-esteem to the support of her adoptive family and community—and now to the DNA she shares with her sisters as well.

The similarities between Jen and Christina are even more striking, starting with their strong physical resemblance. Jen calls them “unofficial official twins.” While growing up apart, each was enamored of all things twin-like, including the 1990s sitcom Sister, Sister, about reared-apart identical twins portrayed by twin actresses Tia and Tamera Mowry. Both girls grew up feeling somewhat like only children, each being the youngest in her family and separated by many years from the sibling closest in age. Now both believe they have fulfilled their childhood vision of growing up with a close sister. When they have been mistaken for twins, they have happily played along. They even enjoy the same foods—growing up, each independently told her family she’d never refuse dessert because “a separate part” of her stomach was dedicated to sweets.

The Power of Kinship

The evolving bonds between Dominique, Jen, and Christina put a fresh face on the scientific study of kin relations.

My reared-apart twin research reveals that close relationships can develop quickly between such pairs. In 2003, I found that over 70 percent of reunited identical twins and nearly 50 percent of reunited fraternal twins recalled feeling closer than or as close as best friends upon first meeting. These figures jumped to about 80 percent and 65 percent, respectively, for the closeness they reported feeling when surveyed. Yet only about 20 percent of the twins felt the same way toward unrelated siblings they had always known. In 2011, I reported my findings that most parents of young separated twins observed an immediate rapport between the children when reunited. These findings suggest that perceptions of similarity (mostly behavioral) are the social glue that draws and keeps reunited twins and siblings together, underlining the universal importance of family.

Dominique and Christina are close to Camelia today, and Jen had an emotional first meeting with her birth mother at Dominique’s home in 2009. Jen assured Camelia that she had had a wonderful childhood with a wonderful family and that her adoptive parents had taught her not to judge others.

Dominique and Jen quickly hit it off in their first phone call, though at the time, Dominique wondered, “Were we relatives when we met, not quite sisters—or were we strangers acting like sisters?” She’s certain now: Once-conscious efforts to keep each sister in the loop are now automatic for her, and the sisters have forged new memories they can share together by doing what they call “childhood stuff.” They have found that it’s easy to connect when your behaviors, talents, and interests coincide.

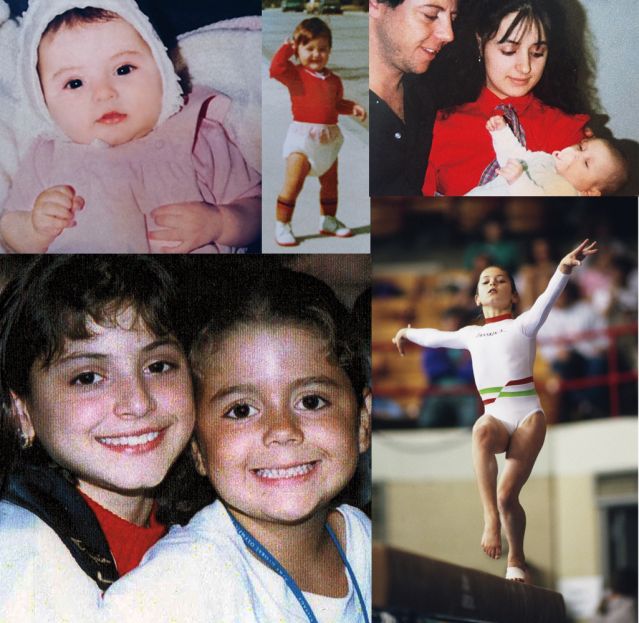

AN OLYMPIAN BIG SISTER: Dominique Moceanu (clockwise from top left) as a baby in 1981; walking at nine months old; with parents Dumitru and Camelia in California, 1981; competing at age 10 in the 1992 Junior National Championships in Columbus, Ohio; and at age 14 with sister Christina, age 6. Photos courtesy of Dominique Moceanu

The Source of Talent?

Recent advances in molecular genetics have redirected the aims of behavioral genetics toward finding specific genes that underlie specific traits. In 2008, Russian scientist I.I. Ahmetov and colleagues found that the gene HIF1A was associated with human muscle activity. Other genes have been studied for their apparent connection to artistic gymnastics, Dominique’s sport—a 2015 review by Italian researcher Myosotis Massidda described seven different genes thought to underlie a genetic predisposition for gymnastics. For example, one form, or allele, of the ACTN3 gene, the alpha-actinin-3 protein, seemed to enhance sprint and power performance in males and possibly in females.

Jen’s sport, rhythmic gymnastics, combines dance, artistic gymnastics, and acrobatics. A 2014 study found higher frequencies of DRB2 and FTO alleles in rhythmic gymnasts compared with a control group. These genes are linked to low body mass index (BMI) and low fat mass, characteristics likely to affect performance. (One suspects that had Jen been born with legs, her first love might have been artistic gymnastics, but we will never know for sure.)

Yet the origins and mastery of physical abilities are complex. In his book, The Sports Gene, David Epstein concludes that genetic effects on physical skill reflect the work of many genes, each on its own having a very small impact. Most studies of complex traits like intelligence and weight come to similar conclusions, yet this does not necessarily diminish the importance of individual genetic findings. And none of these findings should detract from the wonder of watching an extraordinary diver, dancer, or gymnast.

Genetics alone can never predict the final result.

Psychological research has found that self-esteem, belief in oneself, parental encouragement, and effective coaching also influence athletic outcomes. A 2006 study by Herbert Marsh showed that gymnasts’ self-concept and performance work in reciprocal fashion—both are determinants and consequences of one another. Jen’s hereditary background “helped her exceed a certain threshold of performance,” Claude Bouchard says. “But most important, given her lack of lower limbs, Jen’s dedication, determination, and will allowed her to remain in the ‘club.’”

University of Minnesota psychologist Thomas J. Bouchard, Jr. (no relation to Claude) agrees. “My own bias is that the perseverance at practice necessary to perfect the skills shown by these sisters is probably heavily genetic and more important than we realize. I emphasize this because normally we would focus on similar musculature. The fact that one sister does not have legs forces us to think about the issue differently.”

Ironically, had Jen been raised by the Moceanus, she might never have developed her extraordinary physical skills. Dumitru’s views of physically challenged children and his single-minded focus on developing Dominique’s potential could have been roadblocks for Jen’s ambitions. The Brickers, while not athletically minded themselves, brought no such biases to the table and fully supported their daughter’s dreams.

Dominique, Jen, and Christina live in Ohio, California, and Texas, respectively. Dominique is a gymnastics coach, choreographer, and motivational speaker, as well as a jewelry designer and founder of Creations by C & C: Dominique Moceanu Signature Collection. Jen tours with acrobatics shows around the country and coaches young gymnasts. In 2009, she was a featured performer on the Britney Spears “Circus” tour. She will release a book about her life, Everything Is Possible, in 2016. Christina, who had once been headed for a career as a volleyball coach, switched gears and now works in retail banking. Despite the distance, the sisters meet whenever they can. Dominique is considering training in aerial gymnastics to potentially perform with Jen. Her daughter Carmen, now 7, might join them.

Near the end of our visit, Dominique reflected that meeting Jen was only possible because a social worker had apparently failed to strike the Moceanu family name from her sister’s adoption papers. Somewhat like their genetic connection, “It was destiny etched in stone,” she says. “There was no other traceable route.”

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity. For more stories like this one, subscribe to Psychology Today, where this piece originally appeared.