Fantasies

Talking to Killers

Former prison psychologist dissects interviews with two child serial killers.

Posted May 5, 2016

For my class on serial murder this semester, I played a tape of an interview with Westley Allan Dodd, a child predator and killer of three boys. He had fantasized about his future victims and made elaborate plans for what he would do with them. Caught after attempting to abduct a six-year-old boy from a movie theater restroom, he admitted to the murders of three other boys in the area of Vancouver, Washington.

Two brothers, Cole Neer, 10, and William Neer, 11, were found stabbed to death in a park. Not far from there, the body of a 4-year-old was dumped.

Searching Dodd’s residence, police found photos of his victims, and a disgusting diary recording his crimes and detailing plans for more. Although he was stopped when he was 28, he'd been molesting boys for 15 years.

In the videotaped interview, he spoke freely about his lust and his treatment of his victims. He believed he deserved to die. His calmness was chilling. When contemplating his death sentence, he chose to be hanged, as he had hanged one of his victims.

Dodd was a good-looking guy with no background of abuse, and no apparent reason why he would have developed this fatal form of pedophilia. So, when Dr. Al Carlisle, a former prison psychologist at Utah State Prison, told me that he’d written a book that included his extensive interviews with Dodd, I wanted to read it.

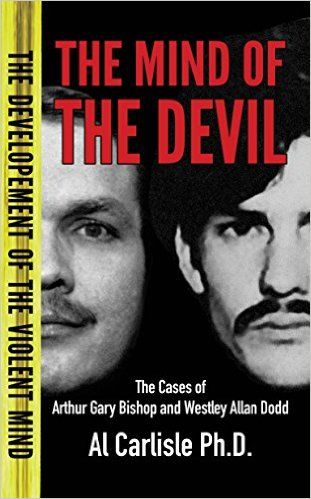

The Mind of the Devil covers Dodd, as well as another child serial killer, Arthur Gary Bishop, from Utah. Carlisle includes numerous quotes from both. (I reviewed Carlisle’s book about his experiences with Ted Bundy here.)

I’ve recently completed a similar project with Dennis Rader, the “BTK” killer in Wichita, KS, Confession of a Serial Killer. Also, in The Mind of a Murderer, I described other mental health experts who decided to dig deep to learn about extreme offenders. Thus, Carlisle’s book is among those rare works that depicts a professional spending a lot of time to listen to and analyze the most disturbing admissions about what some humans have devised to do to others.

He starts with a quote from my favorite writer, Dostoevsky: “Nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer; nothing is more difficult than to understand him.”

Carlisle admits that his own initial response to these individuals was revulsion. But, as a clinician, he understands the need to painstakingly trace their trajectory toward violence. In the introduction, Carlisle says that he had not planned to write a book on these two offenders, but his professional curiosity kicked in. If they were willing to talk and honestly explore, he wanted to know how such seemingly ordinary boys had grown up to become men who killed children for sexual arousal.

“If we are ever to find a way to stop the sexual abuse and murder of children,” Carlisle writes, “we must try to understand them.”

He began with their childhoods and explored their adolescence. He thought he saw their progressions and was able to pinpoint how their desires twisted into deviance.

“My thing with some of the serial killers I’ve talked to,” says Carlisle, “is what has happened in their minds from the time they were children up through the teenage years. Not necessarily why they made their decision, but what happened from making their decision, and how they gradually changed from the time they were a child through their serial killings.”

The interview with Arthur Bishop gets quite disturbing when Bishop describes his consuming obsession with boys. He thought about them all the time. “It’s such a learned behavior,” he states, “learned over so many times, and reinforced so many hundreds of times, you may like to change but you just plain don’t know how anymore.”

Bishop felt helpless and worthless. It became a vicious cycle of trying to feel good, and the one thing that made him feel good was molesting boys. Then he had to dominate and possess them. That meant killing. “The boy is gone, but because you were the one who did it, somehow you’re spiritually responsible for him.”

As he developed into a killer, Bishop’s sense of reality shifted to accommodate what he was doing. So did his moral framework, which had roots in religion. We see something similar with Dodd, who mentions deals with Satan. He makes it clear that early on, the things that he knew were wrong were also too exciting to give up. “If it’s wrong but fun, it’s all the more exciting.”

Alienation and humiliation appeared to be part of Dodd’s development, isolating him into his private fantasy life. Sexual arousal further isolated him. Eventually, Dodd began to expose himself to other children. He got away with it. But then it lost its impact, so he added more daring acts to his fantasy life, which became more dangerous for his targets. Those things that aroused him became the things he repeated.

From these interviews, readers can watch the gradual development, act by act, fantasy by fantasy, of how someone becomes a child killer. In the end, Carlisle offers a comparison between these two child killers and draws some conclusions. Sexual addiction is key, along with isolation and loneliness.

This is a revelatory book, a solid step toward eventual prevention and treatment, especially when placed alongside other similar criminal autobiographies. I saw plenty of details in here that matched items Dennis Rader had told me. A full qualitative analysis of these first-person dark narratives has real promise.