Anger

Taming Teens' Anger

Here's how caring adults can connect with teenagers through honest emotions.

Posted July 26, 2024 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Teens are immature emotional expressers because their brains are still developing.

- Anger is an important emotion, and it takes time to learn how to use it in healthy ways.

- Teens learn to express themselves in the context of connected relationships with supportive adults.

Enraged, affronted, furious, seething, annoyed, resentful, indignant, irate, irritated, irked, spiteful, and ticked off. There are many flavors of anger.

Anger is complicated, especially when it comes to teens. The overactive emotional center in the teen brain (amygdala) plus the immature thinking part (pre-frontal cortex) that helps to regulate self-control make teens immature and inartful emotional expressers. Anger has important functions that serve to get needs met. Anger signals when a boundary has been crossed physically, emotionally, or morally. Anger elicits urges people to fight, lash out verbally, protect, assert, protest, or otherwise take needed action.

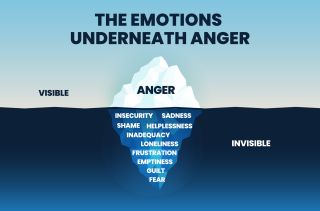

As teens learn what feels meaningful, morally right, and authentic for them, they will feel and will need to express anger. Anger is also often what is called a secondary emotion. It is a safer, more protective emotion than whatever vulnerable emotion may lie underneath, such as hurt, embarrassment, sadness, rejection, guilt, shame, or fear. Supportive adults play an important role in shaping how teens understand and learn to express themselves as an adaptive means for getting their needs met.

I often work in therapy with teens to be more in touch with and skillfully express their anger, as in this example:

Jeremiah came into our session with arms crossed and an angry expression. “What’s going on? You seem…angry?”

“I am! My dad can be such an asshole.”

“What happened?”

“He picked me up from practice and instead of just waiting in the car, he met me over at the field and made some stupid comments to my coach about how maybe we could have had a better game last week if he put me in. I was so pissed. Now, my coach is going to ride me even harder. Why did he have to do that!? I told him specifically I would meet him at the car.”

“Did you let your dad know you were mad about what he did?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“He would just tell me I was being disrespectful.”

“OK. Well, maybe when emotions are high, it can be hard to let him know skillfully that he crossed a line. Could we help you plan a way to talk with him later once your emotions have settled some?”

“No. He won’t listen. Whenever I try to tell him I’m mad about something, he just tells me I am being disrespectful, even when I’m not trying to be disrespectful and just telling him what made me mad.”

Jeremiah sheds light on a common barrier to expressing anger for teens. It is especially tricky for teens when they are angry at the adults in their lives. Parents, teachers, coaches, and other important guiding adults have power over teens and, therefore, leverage to take things away, enact consequences or punishment, and even withdraw affection, which by far may be the most threatening for teens.

The importance of expressing anger in healthy ways

Anger, however, is a real and important emotion, one that inevitably arises in relationships, especially when we care deeply about that relationship. Teens have also expressed feeling guilty about being angry at parents, expecting they may not be able to handle or will overpersonalize teens’ feelings. How can teens learn to express themselves openly if they feel shut down or come to expect that caring adults will invalidate, misinterpret, or hand out negative consequences to honest expressions of anger?

What happens if we explicitly or inadvertently communicate to teens that anger is wrong or unacceptable?

When there is no depressurization valve for the expression of anger, the underlying primary emotions remain stuck as well. Over time, unexpressed anger festers and can manifest as something else entirely, such as persistent anxiety or depression. Other ways chronically unexpressed anger and other difficult emotions may get rerouted is through eating disordered behaviors, self-harm, substance use, sexual acting out, reactivity, or general disregard for rules.

When I explore anger with clients, I often either get a puzzled expression (as in anger feels unfamiliar) or reports that they don’t express anger for very valid reasons. For many teens, at best, anger feels unfamiliar, and at worst, it feels forbidden.

How parents and other caring adults can help

What can adults do to allow for authentic emotional expression by teens, including anger, while also guiding teens on interpersonally effective ways to express such difficult emotions?

1. Remember that teens can be easily overwhelmed by their emotions and are still developing the parts of their brain that mitigate self-control.

When teens attempt to express a valid emotion using unacceptable language or behavior, be clear with them about the difference. Let them know you do want to understand what they are angry about and that you cannot do that when their behavior or language is inappropriate or disrespectful. Be clear that any consequences are for a behavior and not for any emotion. Then, encourage the emotion to be expressed more appropriately when you and they are ready.

2. If you are worried that a teen may act unsafely or impulsively when they are angry or intensely upset, share those concerns openly.

Try not to walk on eggshells around them or back down from appropriate accountability or boundaries. If they do act unsafe, destructive, or aggressive, those behaviors need to be responded to with appropriate supports and perhaps professional help.

If adults try to appease, avoid, back off from asserting a limit, or shut down the honest expression of anger, it can signal that we and they should be afraid of emotions. What is really needed is the kind of help that allows for the development of distress tolerance, emotional regulation, self-regulation, and effective communication to address underlying concerns that may be triggering the emotional intensity.

3. Think about your own attitudes about anger and how anger has been managed historically in your family and other relationships.

Practice and model the honest yet tempered expression of anger so words can help others understand your needs without those words resulting in a personal attack, insult, emotional withholding, rejection, or shame. Do this also in your other relationships and environments observed by the teens in your life. If this feels difficult, access your own supports rather than eliciting guilt or invalidating the expression of that teen.

4. When expressing anger to teens (because they will make us angry), wait to do so until your expression can be appropriate, respectful, and nonjudgmental.

Keep your end goal in mind. What do you want the teen to understand, learn, or accomplish? Remember that time is on your side, so step away, take a break, and come back when the response can be thoughtful.

Very few things are urgent except in situations that pose an imminent threat. When teens know you are angry and you make them wait to hear from you, they have time to contemplate their behavior and accept that there will likely be a consequence coming their way. It also helps them reflect on their own behavior rather than unskillful, angry adult reactions.

Describe the reason for your anger and connect it to the underlying primary emotions. We, as caring adults, usually become angry when we are scared, worried, hurt, disappointed, or embarrassed, which can make more sense to adolescents.

Teens are struggling with mental health broadly. They learn, grow, and feel supported in the context of connected relationships. When adults in various roles in teens’ lives model and allow for the open expression of emotions, particularly the ones that feel most difficult, it builds healthy relationships for teens with others, with their emotions, and within themselves.